A comparative look at the bizarre works of two great artists

While the name Giuseppe Arcimboldo may seem unfamiliar, his fantastical portrait paintings are recognizable to many. When looking at these works from a distance, they appear to depict the faces of people. However, as one approaches the paintings, something amazing begins to appear from within the art. The human subjects are actually comprised of many objects, ranging from various flora and fruits to sea creatures and other beasts, all carefully arranged to create the impression of a human figure.

Around 80 species of plants can be identified in this painting entitled “Spring” by Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Do you recognize any?

Around 80 species of plants can be identified in this painting entitled “Spring” by Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Do you recognize any?

Though the Milanese-born Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526-1593) painted realistic portraits, religious works, and even drew costume designs for theatre as well, his imaginative composite heads ended up being the legacy for which he is remembered centuries later. Rather than the product of a deranged mind, Arcimboldo’s works reflect the cultural tastes of his day.

As a late 16th century Mannerist painter, Arcimboldo sought to express the relationship between humans and Nature. He enjoyed the favor and patronage of the Habsburg court in Vienna and later Prague, both of which embraced humor and the Renaissance fascination with natural studies, riddles, puzzles, and the bizarre.

Recently, “Arcimboldo: Nature into Art,” the first comprehensive exhibit on the Italian painter in Japan, opened its doors at The National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo. Visitors can now view many of the artist’s most famous works up close and in person. Perhaps the most striking to viewers will be the remarkable detail and realism with which Arcimboldo carefully depicted each object in his paintings. His scientific approach to the study and reproduction of nonnative species as seen in the conglomeration of 60 or so sea and aquatic creatures that make up this woman’s profile in “Water,” reveal a curiosity about the natural world.

Various aquatic creatures create the face of woman in the painting “Water” by Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Red coral appears to form a crown on the top of her head while a string of pearls creates a necklace.

Various aquatic creatures create the face of woman in the painting “Water” by Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Red coral appears to form a crown on the top of her head while a string of pearls creates a necklace.

Why incorporate plants and animals? The meaning behind these portraits

But why did Arcimboldo choose to use a jumble of animals and other objects in his “The Four Elements” series? Or masses of flora and fauna in “The Four Seasons” series? Arcimboldo’s wonderful artistry actually presents a political message about the commissioner, Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor. By creating harmony out of the chaotic swarms of various natural elements, Arcimboldo’s figures glorify the ruler as a champion of order. Arcimboldo’s artwork conveys not only how his patron brought structure and harmony to the world, but also goes as far as to suggest that the Habsburgs control the primal elements and the natural world, too.

In “Earth,” the lion which symbolizes strength and nobility along with the fleece which signifies authority are thought to refer to the Habsburg rulers.

In “Earth,” the lion which symbolizes strength and nobility along with the fleece which signifies authority are thought to refer to the Habsburg rulers.

The painting “Earth” consists of many land animals skillfully arranged to resemble a male profile. The antlers of several species of deer form a crown around the man’s head, while the lion and sheep serve as symbolic references to the Habsburg dynasty.

While these pieces attest to the political power of the court, Arcimboldo also painted witty and grotesque works to humor his patrons. An example can be found in his unflattering depiction of the vice-chancellor Johann Ulrich Zasius in “The Jurist,” who had a reputation for being insincere, or dare we say, “two-faced.” Arcimboldo bestowed his subject with a countenance composed of poultry and fish, and a body of books, which criticizes the lawyer as being inhuman—a concept that still exists today. Apparently, the likeness of the subject along with its humorous jab earned this work and its creator great praise.

The Arcimboldo of Japan

Those visiting the exhibit, and especially those familiar with Japanese art history, may look at Arcimboldo’s composite portraits and feel as if they have seen something similar among Japanese works of art… Around two hundred years following the passing of the Italian artist, an ukiyo-e artist named 歌川国芳 (Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1797-1861) shot to stardom in Edo-period (1603-1868) Japan with his dynamic 武者絵 (musha-e, woodblock prints of legendary warriors).

Kuniyoshi later earned a reputation of being a master designer of playful pictures called 遊び絵 (asobi-e), ranging from comical caricatures and visual tricks like trompe l’oeil and shadow puppets to composite drawings.

A well known cat lover, Kuniyoshi often incorporated felines into his prints. Can you spot the cat designs decorating the outer robe of the warrior Nozarashi Gosuke?

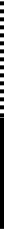

“Nozarashi Gosuke” from the series “Men of Ready Money with True Labels Attached” by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1845, polychrome ink on paper. Press release flyer advertisement for a Kuniyoshi exhibition at the Bunkamura Museum.

“Nozarashi Gosuke” from the series “Men of Ready Money with True Labels Attached” by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1845, polychrome ink on paper. Press release flyer advertisement for a Kuniyoshi exhibition at the Bunkamura Museum.

If you look closely at the skull motifs, you’ll notice that these bones are actually made up of many white cats. The wooden geta shoe hanging off of his sword too eerily resembles a skull as well.

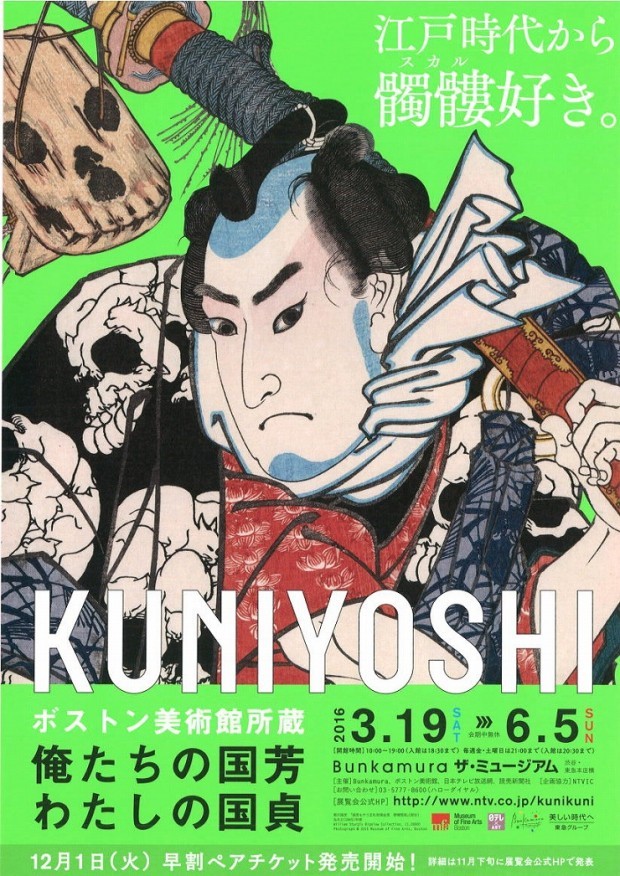

The following 寄せ絵 (yose-e, “gather together picture”) print takes the concept a step further and features a creation not unlike Arcimboldo’s composite faces. Rather than plants or objects though, Kuniyoshi uses human figures in various acrobatic poses to form the figure of a man. The artist’s careful arrangement naturally creates the contours of the face, red loincloths form the man’s gums while a sprawled out figure creates the impression of a nose. One cannot help but laugh at the bizarre arrangements and humorous poses of the people.

“At first glance he looks very fierce, but he’s really a nice person” by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, circa 1847-1848, large-sized polychrome prints, Gallery Beniya.

“At first glance he looks very fierce, but he’s really a nice person” by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, circa 1847-1848, large-sized polychrome prints, Gallery Beniya.

In the next print, we find comical frogs as 歌舞伎 (kabuki, Japanese theatre) actors. Thanks to Kuniyoshi’s imaginative mind, we can also clearly imagine the wild exaggerated gestures of kabuki being enacted by these amphibians. But why frogs and not the real kabuki stars themselves? Similar to Arcimboldo, Kuniyoshi’s works held a hidden political message as well. Rather than praise for the rulers though, Kuniyoshi went against them.

“All kinds of frogs” depicts famous heroes of the kabuki stage played by frogs by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, polychrome woodblock print, circa 1875, Edo period. Image: Library of Congress

“All kinds of frogs” depicts famous heroes of the kabuki stage played by frogs by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, polychrome woodblock print, circa 1875, Edo period. Image: Library of Congress

During the mid-19th century, portraits of kabuki actors and courtesans were banned by the Tokugawa government, who deemed this form of celebrity worship as a weakening of public morals. In order to circumvent these restrictions, 浮世絵 (ukiyo-e, “pictures of the floating world”) artists dreamed up caricatures of commoner’s idols as cats, frogs, foxes, and other creatures. The lines blurred between reality and the unreal, and between animals and people in these inventive illustrations. Audiences greatly enjoyed these riddle and puzzle-like prints that snubbed the government’s attempts to suppress their culture and entertainment.

The imaginative worlds of Arcimboldo and Kuniyoshi

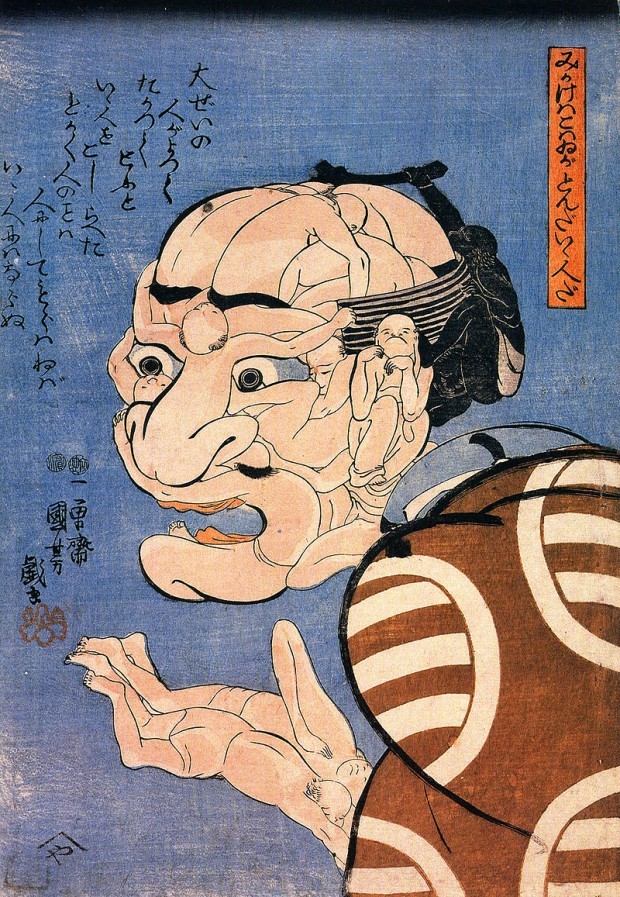

In Arcimboldo and Kuniyoshi’s worlds where things are not always as they appear, both artists tried their hands at upside down images. The first painting could be a work depicting roasted meats on a silver platter. However, when flipped the meats surprisingly seem to take on the form of a grotesque head wearing a hat.

“The Cook” by Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Can you see the face?

“The Cook” by Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Can you see the face?

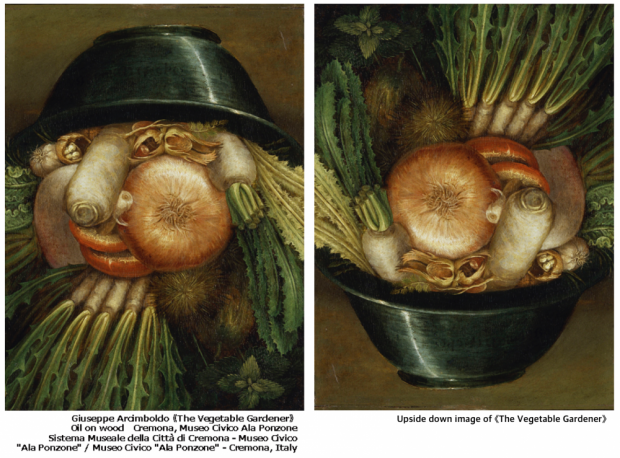

Similarly, the following image could depict a bowl of vegetables, which could have earned Arcimboldo the honor of being the first still-life painter. Yet, when turned upside down, the assembled vegetables create the face of a bearded individual. Arcimboldo cleverly used the products of each person’s trade—prepared food for a cook and produce for a gardener—to fashion the portraits of various workers.

“The Vegetable Gardener” by Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Perhaps this piece inspired Caravaggio, who shortly afterwards painted the first still life of vegetables and gained fame for his still life work.

“The Vegetable Gardener” by Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Perhaps this piece inspired Caravaggio, who shortly afterwards painted the first still life of vegetables and gained fame for his still life work.

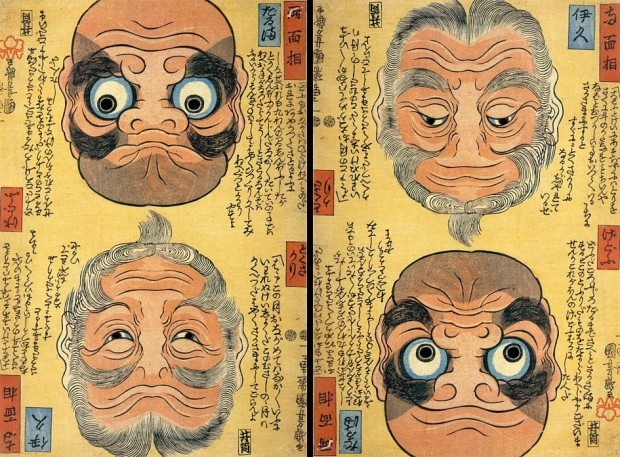

Meanwhile, Kuniyoshi’s 上下絵 (joge-e, “two-way pictures”) print shown below depicts the faces of 達磨 (Daruma, the founder of Zen Buddhism), and Tokusakari, an old man character from a famous 能 (Noh theater) play, on the left-hand side. Both of these men are considered “good.” When these images are inverted as seen on the right-hand side, the same faces transform into two other characters. Daruma becomes a gedo, an evil person or heretic, while Tokusakari appears as Ikyu, the rival character from the famous kabuki play 『助六』 (“Sukeroku”). In other words good men turn into evildoers. With this trick, did Kuniyoshi seem to imply that we all have good and bad within us?

“Double-sided pictures” by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, circa 1849-1850, polychrome woodblock prints.

“Double-sided pictures” by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, circa 1849-1850, polychrome woodblock prints.

While Kuniyoshi did have access to images of some Western art, it is unsure whether or not he had ever seen a copy of Arcimboldo’s paintings. Whether there was any direct influence or not, Kuniyoshi’s brilliant designs stand on their own as testaments to his artistic genius. Today, we can enjoy the imagination of both of these two great artists and compare their fantastical works side by side.

Written by Jennifer Myers.

Exhibition information

The following exhibition is no longer on display.

Arcimboldo: Nature into Art

Venue: The National Museum of Western Art

Schedule: June 20, 2017 – September 24, 2017

Closed: Mondays (open on Monday July 17, August 14, and September 18), July 18

Hours: 9:30 – 17:30 (Fridays and Saturdays 9:30 – 21:00) (Admission ends 30 minutes before closing time)

Admission: Adults 1,600 yen, College students 1,200 yen, High school students 800 yen for day-of tickets