In Japan, as in the West, people produced beautiful paintings and sculptures in the images of their gods and deities. Through these figures, people expressed both their love for their gods and their desire for divine aid and good fortune. In a testament to the mysterious powers of art, people wholeheartedly and unconditionally entrusted their hearts and faith to these works of art. Among the pantheon of various cultures, one of the well-beloved figures is often that of the goddess of beauty and prosperity. Let’s see how the goddesses of beauty from Japanese Buddhism and Roman myth compare with these 2 masterpieces produced in their image.

Female embodiments of happiness and love

Waraku Magazine included the artworks “The Birth of Venus” and “Standing sculpture of Kisshoten” from Joruri-ji Temple in its February・March feature comparing how Western and Japanese art expressed happiness. Below we take a closer look at both the artworks and the roles these goddesses played in their respective cultures.

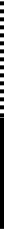

“The Birth of Venus” by Sandro Botticelli

Sandro Botticelli, “The Birth of Venus” (selection), 1485, Uffizi Gallery. ©Erich Lessing/PPS

Sandro Botticelli, “The Birth of Venus” (selection), 1485, Uffizi Gallery. ©Erich Lessing/PPS

The Roman goddess of Venus, adapted from the goddess Aphrodite of Greek myth, was said to have arisen from sea foam. According to Roman myths, Venus was the mother to the ancestor of Rome’s founders, and the deity embodied love, sexuality, fertility, victory, prosperity, and of course, beauty. In their adoration of Venus, the Romans produced great numbers of copies of Greek Aphrodite sculptures. It is said that of all the remaining sculptures of gods from antiquity, those of Aphrodite number the most.

Art featuring Aphrodite/Venus was not only popular during classical antiquity, but enjoyed many revivals in post-classical art such as in the Italian Renaissance and among late 19th-century French Academic painters. This tempera painting by Sandro Botticelli depicts her birth, a popular subject of the day, and has gone on to serve as a symbol for the Italian Renaissance.

Several theories about its meaning surround Botticelli’s painting, including the Neoplatonic interpretation of Venus embodying divine love. Another theory follows the Humanist idea that she represented the ideal love of humanity. Renaissance humanism was popular at the time and centered on classical antiquity. The goddess was sometimes featured in art celebrating weddings as well, and the figure of Venus embodied the perfection of female grace.

Interestingly, while Botticelli drew inspiration from sculptures of antiquity and applied a contrapposto pose to his subject in “Birth of Venus,” the figure of Venus is said to adopt qualities of Gothic art. According to British historian Kenneth Clark, “Her body follows the curve of a Gothic ivory.”

“Standing sculpture of Kisshoten”

“Standing sculpture of Kisshoten” (selection), Important Cultural Property, Kamakura period (1185-1333), height 90.0 cm, color pigment on Japanese cypress with hollow cavity inside, Joruri-ji Temple.

“Standing sculpture of Kisshoten” (selection), Important Cultural Property, Kamakura period (1185-1333), height 90.0 cm, color pigment on Japanese cypress with hollow cavity inside, Joruri-ji Temple.

吉祥天 (Kisshoten, also known as Kichijoten, Kisshotennyo and Kudokuten) is revered as a goddess of beauty, fertility, and prosperity in both Japanese Buddhism and Japanese Shinto myth. Like Venus from Aphrodite, the deity was first adapted into mainland Buddhism from the Hindu goddess of beauty and prosperity, Lakshmi, along with some traits of Krishna, another divinity of love, before arriving in Japan. Worship of Kisshoten in Japan spread throughout the Nara period (710-794) with her image enshrined in many temples such as Todaiji, Saidaiji, Horyuji, and Yakushiji.

吉祥天立像 (Kisshoten ritsuzo, “Standing sculpture of Kisshoten”) pictured above, dates back to the 12th century and is a 秘仏 (hibutsu, a Buddhist image normally withheld from public view) at Joruri-ji Temple in Kyoto. As typical with most images of the deity, this work also portrays her as the ideal feminine beauty from the Chinese Tang dynasty with a softly rounded body dressed in colorful embroidered robes and a jeweled headdress. Her robes are painted with a special coloring method called ungen-saishiki, in which a color repeatedly goes from dense to diffuse, diffuse to dense that was used in the Nara and Heian (794-1185) periods.

Kisshoten’s full cheeks and elegant, crescent-shaped eyebrows also lend a serene and mature grace to her heavenly nature. The renowned Japanese photojournalist, Ken Domon, also famous for his images of Buddhist temples and statuary, exalted this statue as, “the most beautiful woman in Japan.”

You may notice that the goddess clutches a jewel in her left hand. This nyoi-hojo (wish-granting jewel) is tied to her image as a deity who bestows fortune and happiness to those who confess and repent their sins. This jewel helps identify Kisshoten and distinguish her from another Japanese goddess, Benzaiten, who is often conflated with Kisshoten and later overtook her in popularity around the 15th-16th century. Benzaiten is adapted from the Hindu goddess Saraswati, who holds a biwa (a traditional Japanese lute), and is regarded as a patron of art and music.