Japan’s first gold-producing region

I recently made a trip around the Pacific coast of Tohoku for work. Driving a car is not easy, so I relied on the search function on my smartphone and took conventional train lines. Unfamiliar lines, unfamiliar place names. I had never lived outside of Kyoto, so the scenery was refreshing to me, and during the exciting journey, I came across a place that I felt like I had heard of before.

It was on the way to Minami Sanriku (南三陸) after getting off the Shinkansen (新幹線) in Sendai (仙台). I was passing through Wakuya (涌谷) Station on the Ishinomaki (石巻) Line. I glimpsed a sign saying “Japan’s first gold-producing area” which almost made me gasp outloud.

I am not familiar with the geography of the Tohoku region, so I almost passed it by. In Nara-era place names, this was Mutsu (陸奥) Province, Oda (小田) County. In current place names, the town of Wakuya in Miyagi Prefecture was the first place in Japan where gold was discovered in the Nara period.

For Emperor Shomu (聖武), who was building the Vairocana Great Buddha of Todaiji (東大寺) at the time, the discovery of gold in Wakuya in the 21st year of Tempyo (天平; 749) was such an event that he called it the most celebrated event in the country’s history. Until then, gold had been considered a mineral that had to be imported from other countries.

However, the Vairocana Great Buddha, which Shomu invoked, is described in the Buddhist scriptures as a luminous Buddha who radiates the radiance of wisdom and compassion. For this reason, the Great Buddha of Todaiji had to be painted with gold at all costs. Shomu, who was delighted by the discovery of gold, changed the year from ‘Tempyo’ to ‘Tempyo Shoho (天平勝宝)’. He also reported the discovery of gold to the shrines in the country and even conferred titles on the Mutsu provincial governors and those who had discovered and casted the gold.

Even today, in the 21st century, gold is still a highly valuable metal and continues to be traded at high prices. Among the various gems and precious metals, gold is arguably the most popular. However, if we peruse the history of Japan, we cannot ignore the existence of Buddhism as the catalyst for gold to become a renowned jewel.

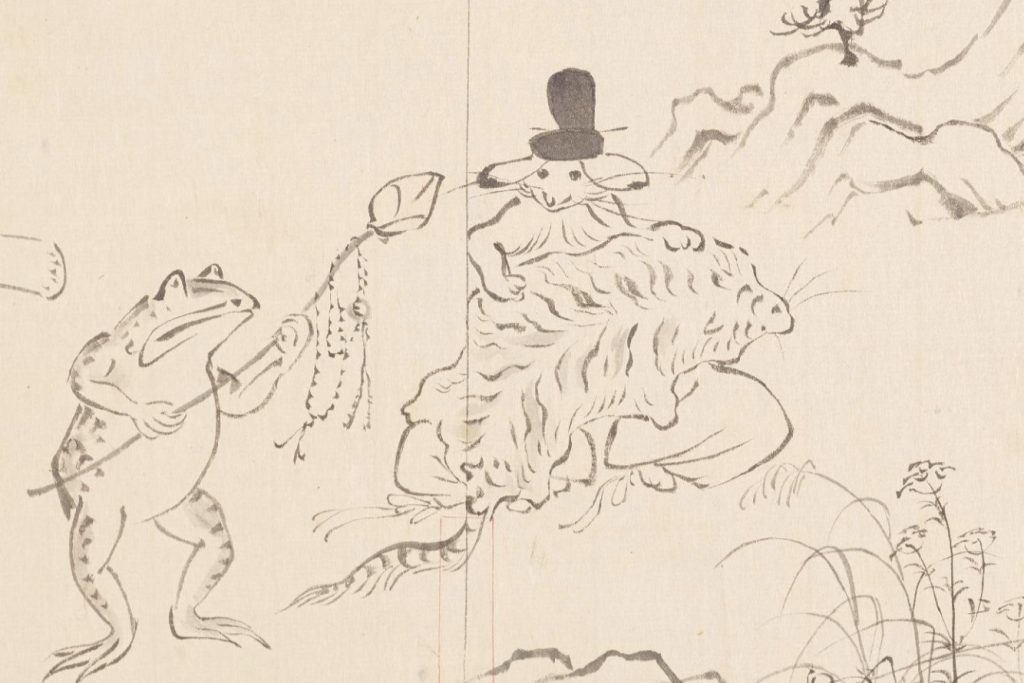

In the Kofun (古墳) period, which preceded the Nara period, gold, which came from the far reaches of the sea, was a metal used only as an ornament for people of noble status. Various gold-plated ornaments have been unearthed from burial mounds around Japan, including the Omishinkanji (小見真観寺) kofun in Gyoda (行田) City, Saitama (埼玉) Prefecture. In addition, two pairs of shoes made of gold-plated copper plate were found in the Fujinoki (藤ノ木) kofun in Asuka (明日香) Village, Nara Prefecture, which caused a huge boom in ancient history in the 1980s following its discovery and excavation, as well as gold-plated crowns and harnesses.

These shoes are 43 cm long at their largest and 15 cm wide at their widest. Each pair has more than 100 pacesetters, which are circular or fish-shaped metal fittings attached to the ends of twisted wires. The shoes are too large and the pacesetters are attached to the soles of the shoes, the part of the shoe that would normally be in contact with the ground, so they are thought to have been impractical. However, even so, the shoes are a luxury that is hard to find even today, with the entire shoe shining in gold.

Buddhism, which was inseverable from shiny gold

In ancient times, the only colours that existed were the colours of nature. Gold, shining like the sun, would have seemed more glamorous than we perceive it to be today. In fact, the majority of gold objects from before the Nara period have been found in ancient burial mounds, and it is extremely rare to find gold in the ground. This is because gold was a special symbol of power, more than just an ornament. Gold at this time was probably a very precious commodity that ordinary people had little opportunity to see.

However, the introduction of Buddhism to Japan in the mid-sixth century overturned such notions of gold. According to the Nihon Shoki (日本書紀), King Seimei (聖明王) of Baekje (百済), who encouraged Buddhism in Japan, sent a gilt bronze Buddha of the

Shakanyorai (釈迦如来) Buddha and sutras, which Emperor Kinmei (欽明) received and said: “This Buddha is majestic and beautiful and I have never seen anything like it.”

I mentioned earlier that the Vairocana Great Buddha is described in the Buddhist scriptures as a luminous Buddha. Similarly, Shakanyorai Buddha is also described in Buddhist teachings as having a ‘golden phase’, i.e. his whole body is golden.

Today, most of the Buddhist statues we see in temples in Japan have a desolate colouring that reveals the age-old woodwork. However, most of them were not only painted gold all over, but also had blue eyes and red lips, in accordance with Buddhist teachings. In other words, the calm colours of Buddhist statues that we perceive as ‘uniquely Japanese’ are merely the result of the colouring that has peeled off over the years. Gold was inseverable from Buddhism.

For this reason, as Buddhism spread in Japan, the consumption of gold seems to have increased dramatically. Newly created Buddhist statues were decorated with gold brought from overseas, and gold was also used extensively on Buddhist ritual utensils and temples themselves to show the prestige of the Buddha. At first, Buddhism was the religion of only a few of the ruling class, but temples were eventually built in various parts of the country, and as the teachings spread to the common people, the golden glow also came into contact with a large number of people. Whether or not it was an object that could actually be possessed, it can be said that the Japanese awareness of ‘gold’ was greatly changed by the Buddha Dharma.

‘The history of jewellery is, in other words, the history of society itself.’

A look at the literature of the Nara period reveals that there are not many examples of gold being used as the type of jewellery we associate with it today. One of the few examples is a poem by Yamano-ueno Okura (山上憶良) from the Man-yoshu (万葉集): ‘What is silver, gold, and jewels, but the most precious of treasures – a child’s frown or a child’s smile?

This is one of the representative poems of Yamano-ueno Okura, who is said to have been fond of children, and is saying that no matter how much silver, gold, and jewelry there be, treasure is more precious than a child. However, there are no clues as to the form in which gold, silver and jewellery he is referring to here.

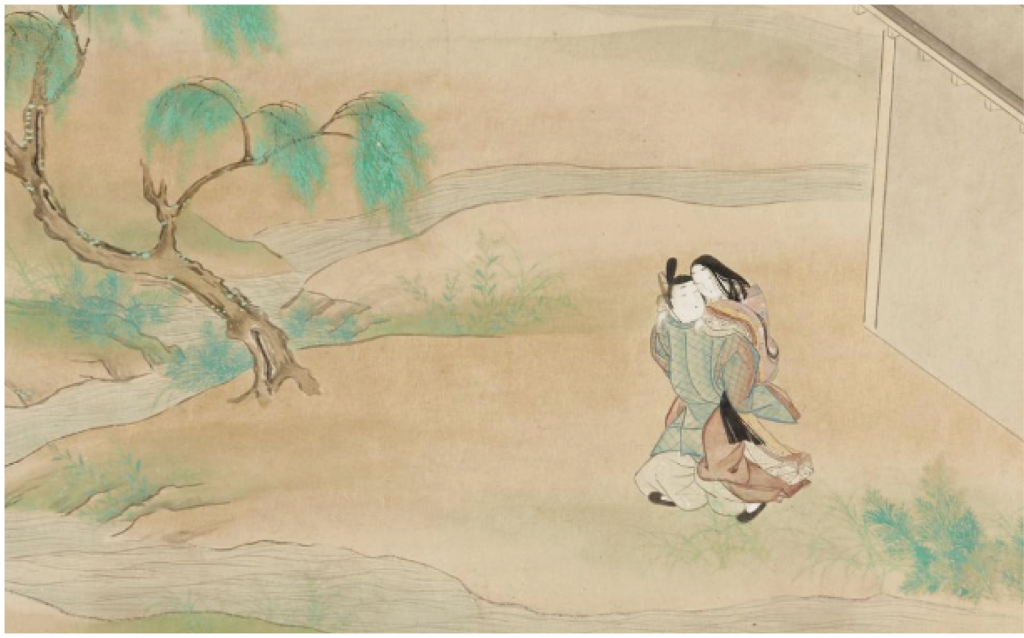

By the Heian period, some 200 years after the time of the Man-yoshu, gold was synonymous with luminous objects and appeared in a variety of historical texts. In Taketori Monogatari (竹取物語), for example, after finding Princess Kaguyahime (かぐや姫), Taketorino okina (竹取翁) frequently found bamboos filled with gold in their joints and made a fortune, while Kaguyahime herself begged her suitor for a branch of gold with a silver root and a Horai-no-Tama-no-Eda (蓬莱の玉の枝), which bears white jade as its fruit.

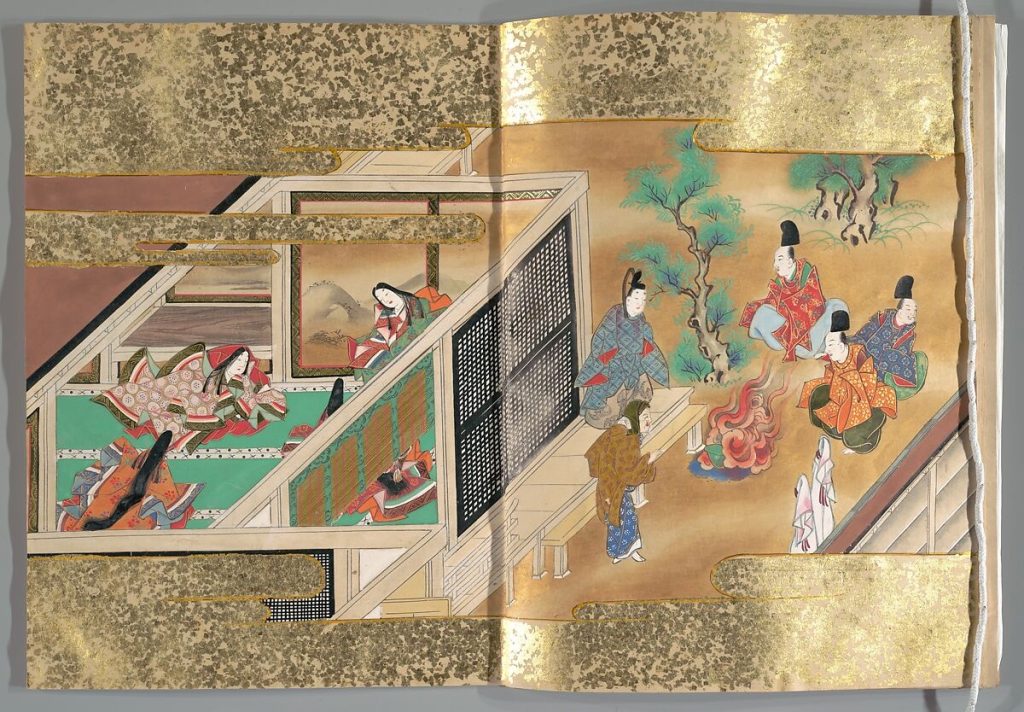

It is interesting to note that Murasaki Shikibu (紫式部), the protagonist of the NHK historical drama ‘Hikaru kimi he (光る君へ)’, often describes goldsmiths in her work ‘Genji monogatari (源氏物語)’, in particular in the ‘Yadorigi (宿木)’ chapter: ‘He summoned many craftsmen who made various kinds of work such as agarwood, rosewood, silver, gold and so on. It is interesting to note that this is how the text reads. In other words, there were goldsmiths in this period who made goldsmith’s work that was pleasing to the eye. This is an example of the acceptance of gold, which came to be seen by many people after the arrival of Buddhism.

Today, gold continues to increase in price and increasingly is used as a commodity, rather than to adorn people and society. However, Japanese people’s feelings towards gold have changed dramatically in the past, in line with changes in society. So there may come a day in the future when we will look at gold in a different way. The history of jewellery is, in other words, the history of society itself.

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/235127/