Shosoin Treasures, as well as in the ancient ‘Gishi Wajinden’

Texts Sawada Toko

Pearls, or nacre, are the most prestigious of all gemstones and are often used as jewelry for formal occasions. The soft glow of pearls, nurtured for many years in their mother shells, has a serenity that differs from that of ores, which are polished and cut to a beautiful shine.

Worldwide, pearls have been prized since B.C. in ancient Egypt and China, and many natural pearls have already been discovered in Japan from Jomon-era sites.

Japan is an island nation surrounded by the sea. For this reason, pearls from the natural world must have been a familiar treasure to the ancient Japanese. In the famous ‘Gishi Wajinden (『魏志倭人伝』)’ , which describes Himiko (卑弥呼), the queen of Yamataikoku (邪馬台国), it is written that around the middle of the 3rd century, a 13-year-old girl named Toyo (台与), who succeeded Himiko, offered ‘5,000 holes of white pearls’ along with 30 male and female slaves and 20 pieces of brocade to Gikoku (魏国). The reason for writing ‘5,000 holes’ instead of ‘5,000 pieces’ is thought to be that the pearls had holes drilled in them and threaded through them.

The Nihon Shoki, a history compiled in the Nara period, records an anecdote that during the reign of Emperor Ingyo (允恭), the 19th emperor, a huge pearl the size of a peach was found in a large abalone on the seabed of Awaji Island in present-day Hyogo Prefecture. The man who discovered the abalone was a diver named Osashi (男狭磯) from Awa Province (present-day Tokushima Prefecture), who entered the sea with a rope tied around his waist and caught the abalone from a depth of 60 fathoms (about 90 meters). Perhaps because he dived so deep into the sea, Osashi himself died soon afterward, but it is not difficult to imagine that pearls were collected in a similar manner in ancient times.

So what were the pearls used for after they were brought ashore? The aristocrat Oh-no-Yasumaro (太安萬呂), who died in the first half of the eighth century, was the compiler of Japan’s oldest extant book, the Kojiki (古事記 : Records of Ancient Matters), and his tomb, discovered in Nara City, Nara Prefecture, some 40 years ago, contained four pearls along with cremated bones and a bronze epitaph. Later investigations revealed that the pearls were Akoya pearls from the Akoya pearl oyster, and as there were no traces of fire, it was likely that they were placed in the tomb with the epitaph after cremation.

Oh-no-Yasumaro was from a clan called Ouji (多氏), based in the vicinity of Tawaramoto (田原本), Nara Prefecture. He had no special connection with the sea. There are various speculations as to why pearls were placed in his tomb, but no firm conclusion has yet been reached. However, there is no doubt that pearls were highly prized at the Imperial Court in the Nara period, and the Tokyo National Museum, for example, has a collection of ‘Gyokutai Zanketsu (玉帯殘闕)’, which is said to have been used by Emperor Shomu and was made into a sash by braiding pearls and glass beads with coloured thread. The Shosoin, which also houses a large collection of Emperor Shomu’s relics, includes ceremonial shoes, ‘Nono Gorai Ri (衲御礼履)’, made of leather dyed in Akane (red) and embedded with pearls, lapis lazuli and crystals, and a crown ornament made of variously coloured lapis lazuli beads and 3,000 small pearls, called a ‘raifuku onkanmuri zanketsu (礼服御冠残欠)’, Various ornaments using pearls have been handed down to the present day.

Of these, the Shosoin shoes and crown are assumed to have been used by Shomu, who had already become emperor, on the occasion of the opening of the Todaiji Vairocana Great Buddha in April 752. However, even though it was the occasion of a major national ceremony, it is hard to imagine a crown with shoes decorated with pearls and other jewellery and a number of small pearls. One can’t help but sigh at the opulence of it all.

Is that a pearl or a dewdrop of grass?

The crown of Shomu, as its name suggests, is now broken into pieces, and the parts are stored separately, including the gold, silver and gilt bronze ornamental fittings and the aforementioned hanging ornaments made from a series of lapis lazuli and pearls. It was not broken in the Shosoin over a long period of time, but was in fact accidentally destroyed on its way back to Kyoto on loan from the storehouse to be used as a reference for the crown used in the coronation ceremony of Emperor Gosaga in 1242, 500 years after the opening ceremony.

There is no way of knowing what kind of crown was used as a reference for the crown of Shomu. However, considering the vast amount of pearls used in the crown of Shomu, it is easy to imagine that the crown of Gosaga might also have been made of pearls of some kind.

The majority of pearls handed down from the Nara period to the present, including the ‘raifuku onkanmuri zanketsu’, are all smaller than one centimetre in diameter. The high level of processing technology at the time is astonishing, since holes were drilled in them and they were used like beads.

Today, when we hear the word ‘pearl’, we tend to imagine that all pearls are of a certain size. There are probably some of you who have read this far who may have thought the same. However, since ancient pearls were all natural products to begin with, we must consider that there is a considerable difference between the pearls they saw and the pearls we recognise today.

In Chinese poetry and waka poems, ‘shiratama (white beads)’, appears as a metaphor for pearls. However, if this is the case, for us to really appreciate the mentality of the people at the time, we must read these poems imagining the pearls as much smaller and delicate.

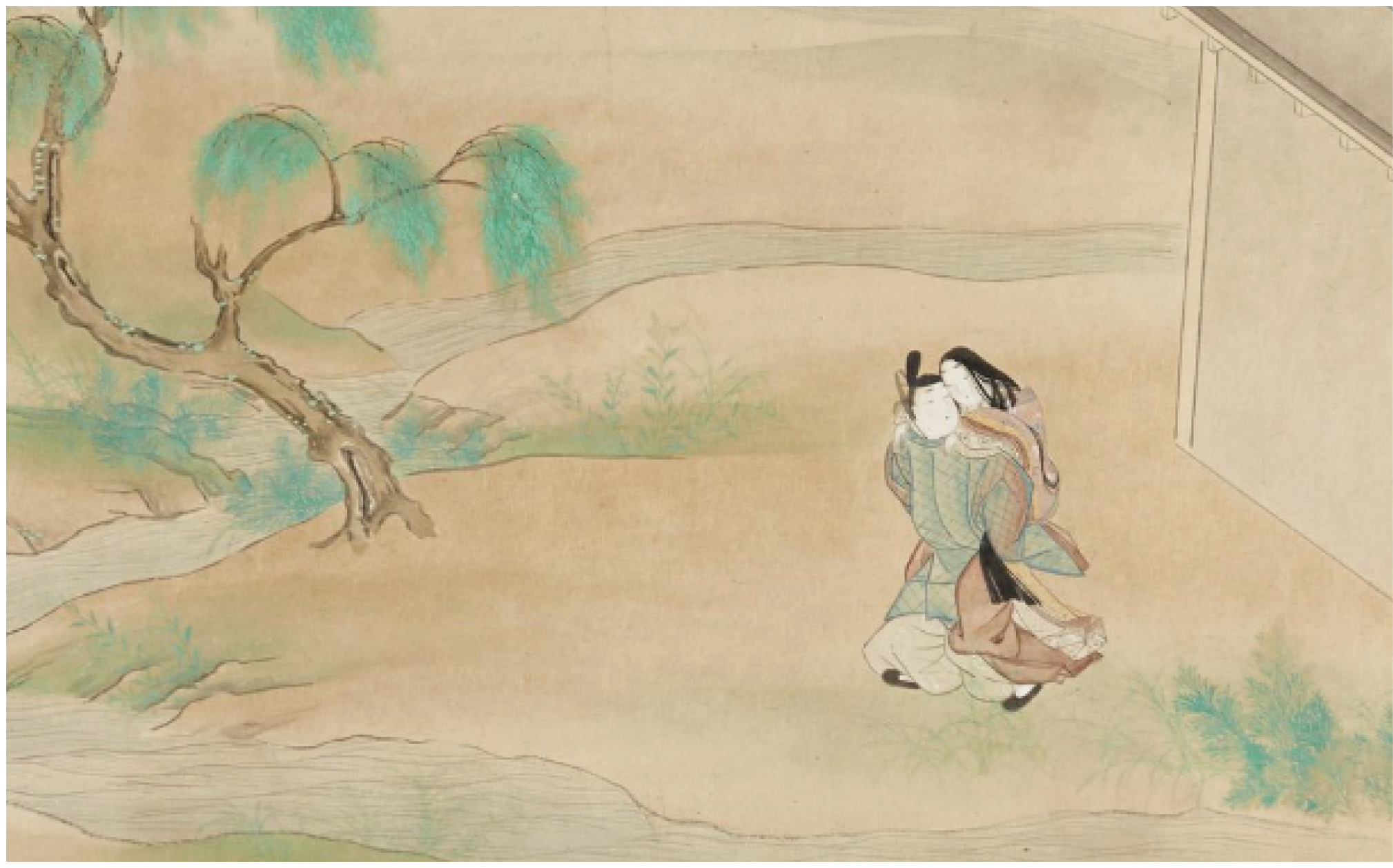

The Ise Monogatari (伊勢物語: Tales of Ise), which is thought to have been established around the 10th century, is a poem-tale featuring a man reminiscent of Ariwara no Narihira (在原業平). In the most famous waka poem of the tale, ‘shiratama’ is also used symbolically.

Shiratamaka Nan zo to Hito no toishi toki Tsuyu to kotaete Kienamashi monowo(白玉か 何ぞと人の問ひしとき 露と答へて消えなましものを)

Meaning: When (that person) asked, “Are (those) shiratama, what are they?”, I should have replied, “(Those) are dewdrops”, and (I) wish I had then also disappeared in the way dew does.

A man is on his way to take his lover away from home, when a woman sees dew on the grass and asks him what it is. The man is in too much of a hurry to answer, but later that night the woman disappears after being devoured by demons in a house that had been rained out. This is actually a parable about the woman’s family who followed them, captured her and brought her back. In any case, the above poem was composed by a man who was saddened by the fact that his lover had disappeared, and who answered, “When my lover asked me if those were pearls, I said they were dew, and I should have disappeared just like that dew”. If you interpret ‘shiratama’ as large cultured pearls as they are today, you cannot understand the transience of the dewdrops on the grass. People in ancient times understood pearls as much smaller beads than today’s pearls, which is why the metaphor perfectly captures the fragility of her existence, disappearing overnight.

We now have easy access to large pearls. The long history of pearl cultivation and the demand for large, beautiful pearls is due to the desire of people who loved natural pearls and were fascinated by their sparkle. In other words, it is the ancient people’s love for pearls that supports the brilliance of pearls as jewellery today.

The story of “Shiratama ka-” is about a man who steals away a woman he has been courting for many years, carrying her on his back. The man wandered into a place where demons lived and hid the woman in a warehouse, but the demons ate her in one bite.

Sawada Toko

Born 1977, Kyoto. Graduated from Doshisha University, Faculty of Literature, and completed the Master’s course at the same university. She made her debut in 2010 with ‘Koyo no Ten(孤鷹の天)’, which won the Nakayama Yoshihide Literature Award(中山義秀文学賞); won the Shinran Prize(親鸞賞) in 2016 for ‘Jakuchu(若冲)’ and the 165th Naoki Prize in 2021 for ‘Hoshi Ochite, Nao(星落ちて、なお)’.

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/223894/