“[My] drawings present completely true-to-life landscapes to give people just a moment of pleasure without the inconvenience of a long journey.” – Utagawa Hiroshige, preface to One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, 1859

Creator of poetic and scenic beauty as seen in the series 53 Stations of the Tokaido and One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), who enjoyed a 40-year long career as one of Japan’s most prolific and successful artists creating dozens of illustrated books, hundreds of paintings and thousands of woodblock prints.

Following Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) with his series 36 Views of Mount Fuji (c. 1830-32), Hiroshige played a leading role in establishing the landscape genre within ukiyo-e.

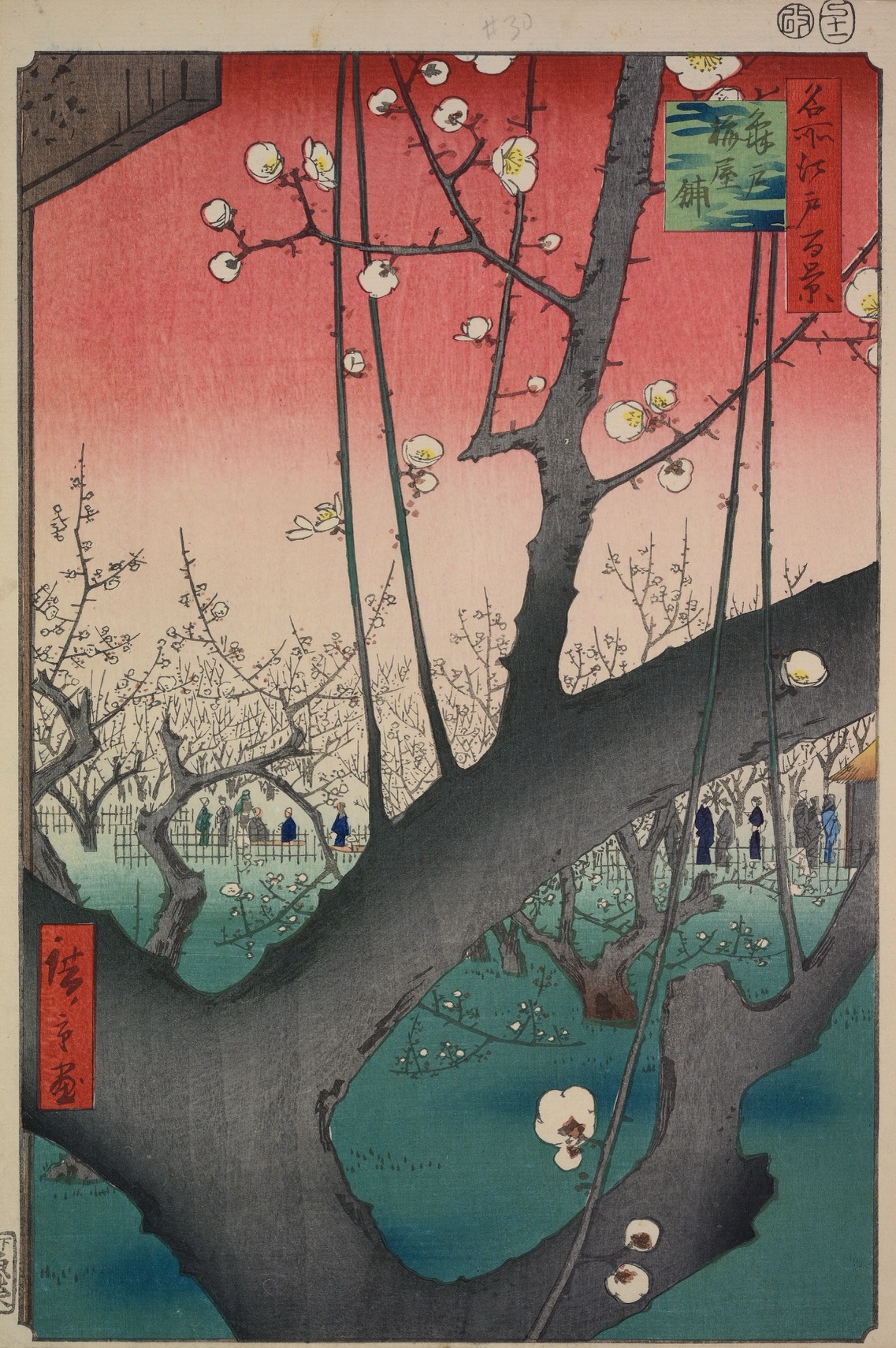

On May 1st, The British Museum in London opened its first ever exhibition on Hiroshige, although having collected his work since 1868 – only ten years after the artist’s death. The occasion for the 2025 exhibition is a major gift of 35 prints by Hiroshige from the collection of Alan Medaugh to the American Friends of the British Museum, along with a special loan of 82 prints from his collection. Widely recognized as the finest collection of prints by Hiroshige outside of Japan, visitors have the rare opportunity to enjoy early impressions in superior condition, such as Awa: The Rough Seas at Naruto (1855) and The Plum Garden at Kameido (1857).

“This exhibition provided an opportunity to share this gift, along with treasures of the Medaugh collection, and beautiful selected examples from the British Museum’s collection and the collections of other important lenders,” curator of the exhibition, Alfred Haft, explains.

With Hokusai and Hiroshige, the new vogue for landscapes and meisho (famous places) took off in the 1830s and 1840s, spurred on by a rising interest in domestic travel. Hiroshige’s portrayals of the two important routes between Kyoto and Edo, the Tokaido (Eastern Coast Road) and Kisokaido (Central Mountain Road) took the artist himself on journeys across Japan. He traveled along the Tokaido Road in 1832, which resulted in his successful series from c. 1833-35.

Hiroshige actually designed more than twenty different series of the Tokaido stations, reflecting the romanticism surrounding the subject. In the spring and summer of 1837 he also traveled along the Kisokaido, taking over the commission from his fellow artist Keisai Eisen (1790-1848).

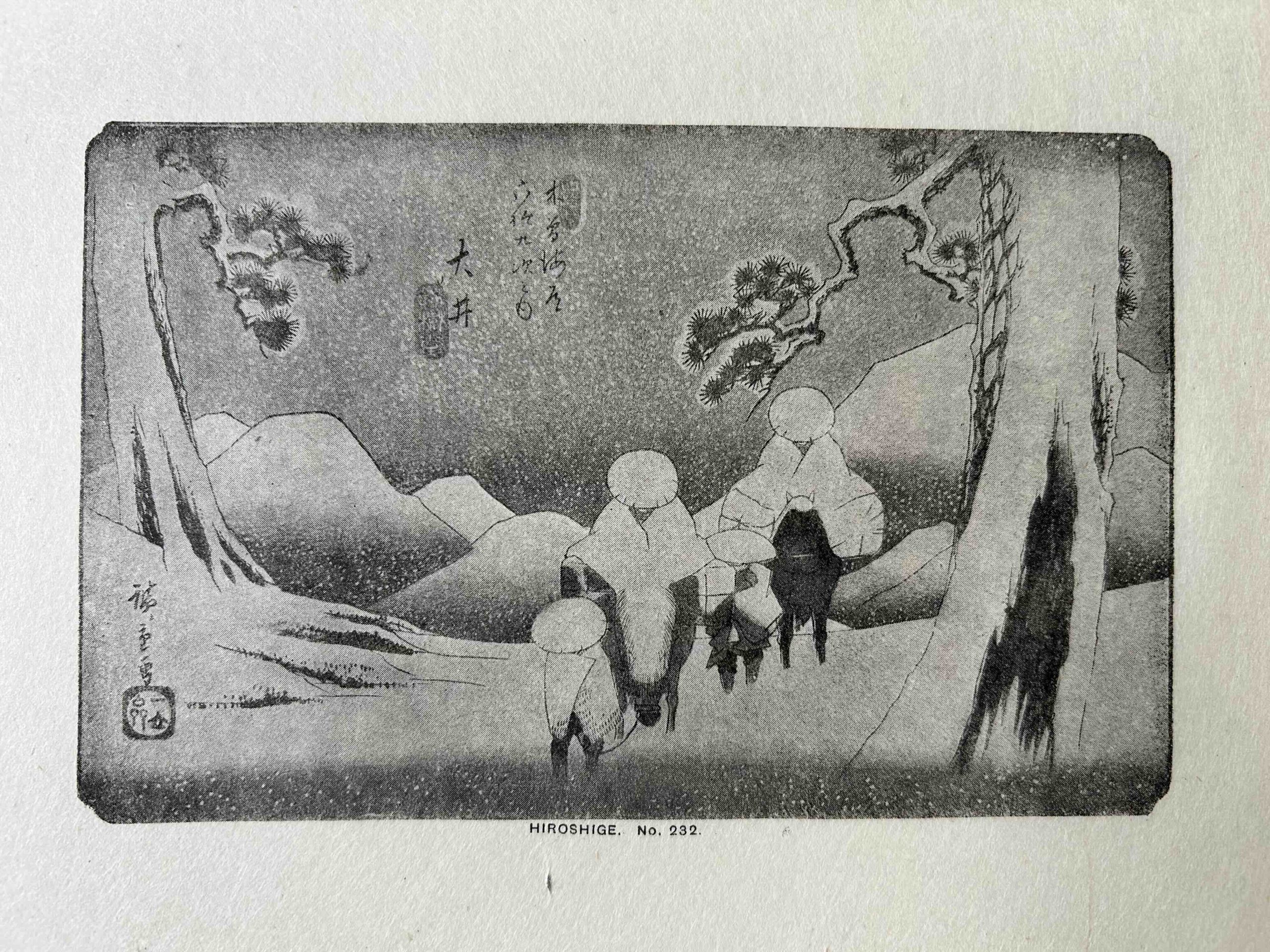

Prints from this series entered the British Museum’s collection in 1906 and were included in the Catalogue of Japanese & Chinese Woodcuts Preserved in the Sub-Department of Oriental Drawings in the British Museum (1916).

“Hiroshige presents a poetic world where people, nature and the fruits of culture work together. His gentle vision leads the viewer into a harmonious world of everyday life presented in brilliant colour. In his own day, he took viewers to new places without them ever having to leave home, and viewers can enjoy the same experience when seeing his prints today,” says Haft.

Legacy

What makes Hiroshige interesting from an art historical perspective is not only his powerful appeal which continues to this day, but also the influence his work had on later generations of artists, especially in the West. Just around the time that Hiroshige passed away in 1858, export of ukiyo-e took hold with the opening of Japan’s ports to trade with the West–– and Hiroshige’s works were among the thousands of prints being exported to the major European and North-American cities. Hiroshige quickly became one of the most celebrated Japanese artists among the European avant-garde.

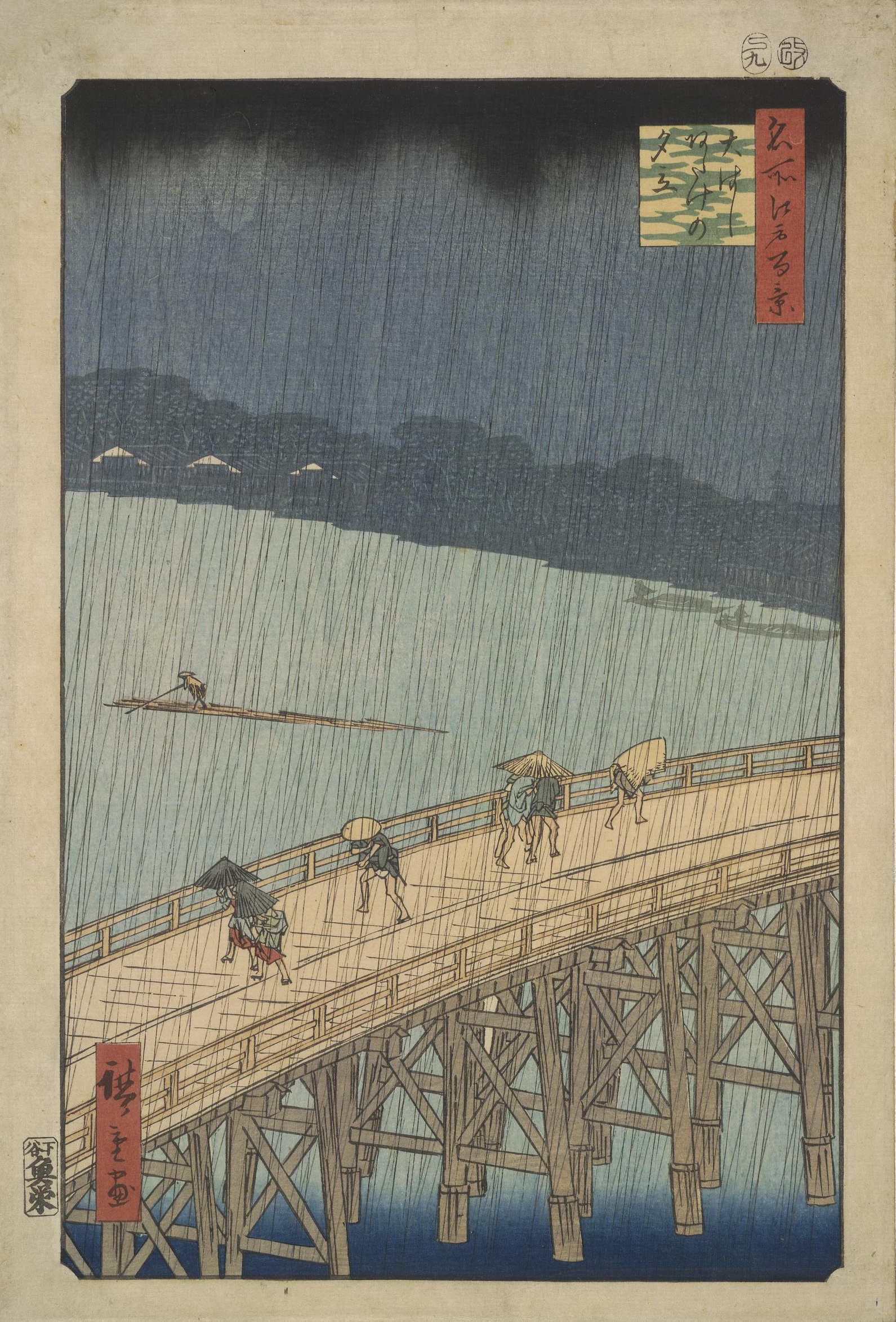

Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), who collected and even tried out as a ukiyo-e dealer, made oil paintings after Hiroshige’s designs. Van Gogh owned the two prints Sudden Shower over Ōhashi and Atake and The Plum Garden at Kameido from the series One hundred Famous Views of Edo, which he had probably bought along with several hundred other ukiyo-e from the Asian art dealer Siegfried Bing in Paris (see also article XX).

In 1887 Van Gogh painted both Flowering Plum Orchard (after Hiroshige) and Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige), now in the collection of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. To make his copy in oil, for Plum Orchard Van Gogh traced his Hiroshige print on a numbered grid – both of which are on display in the exhibition. However, new research by Capucine Korensberg, researcher at The British Museum, interestingly shows that Van Gogh must also have looked at a first edition of the print, from which he based his colours, such as the yellow hearts of the flowers.

While Hiroshige’s work left a strong mark on artists in the late 19th century, his influence continues to this day. A mixed-media print by renowned artist Noda Tetsuya (born 1940), who has led the way for Japanese printmaking since the 1960s, is presented in the exhibition, reflecting the influence of Hiroshige’s famous motif Sudden Shower over Ōhashi and Atake. In February 2002, Noda captured the view of the Millenium Bridge in London from Tate Modern, ecchoing Hiroshige’s use of a dizzying vantage point, as well as the masterful depiction of atmospheric London as seen in works by James Abbot McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), an artist himself strongly influenced by Hiroshige.

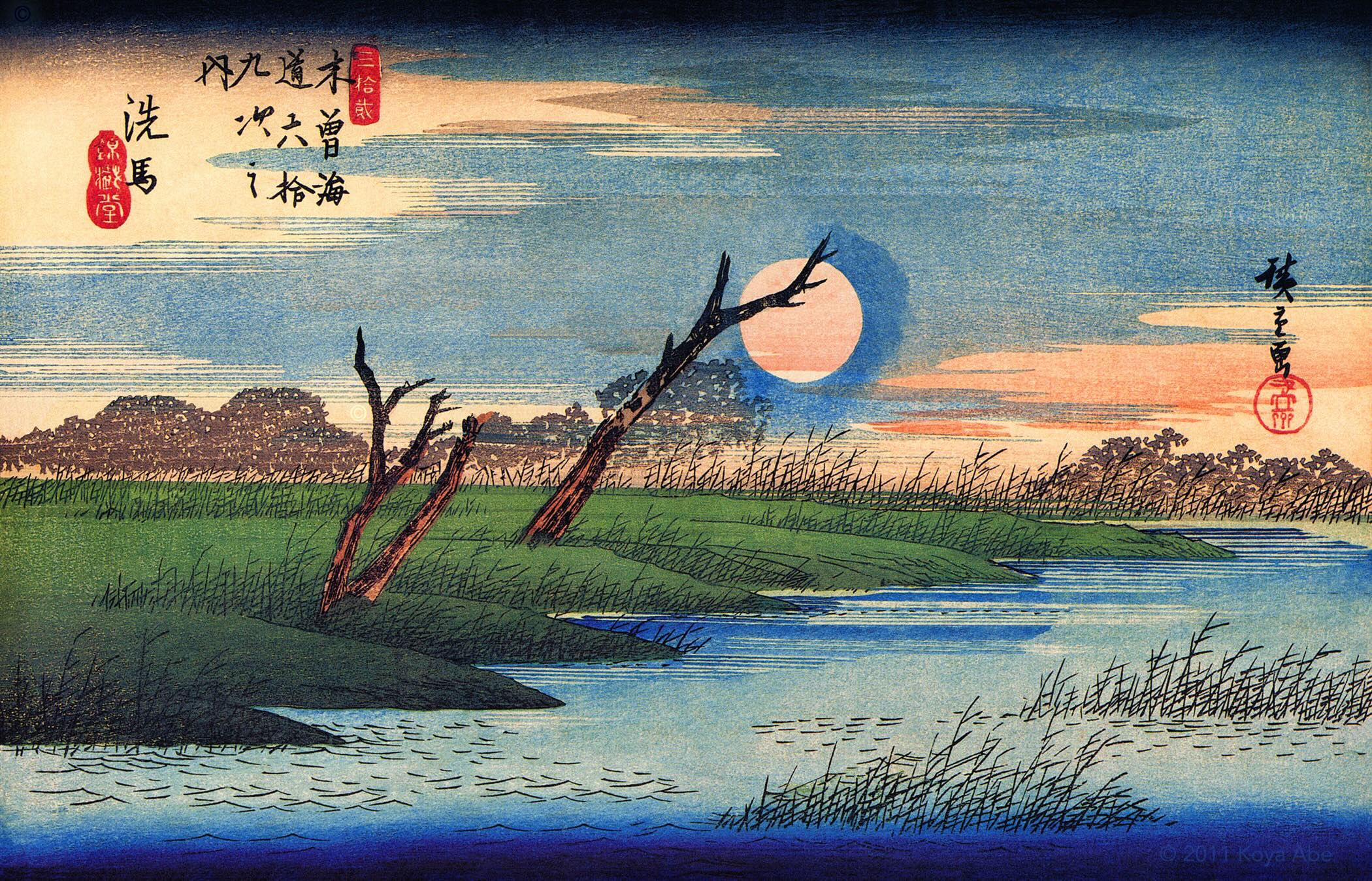

A more direct influence can be found in the work by New York-based artist Koya Abe (born 1964), whose work is represented in the collection of the British Museum, as well as in the exhibition with After Seba from the series Digital Art Chapter Six: Animism (2011).

Since 2000, Koya has been creating digital work based on famous ukiyo-e prints including landscapes by Hiroshige. In a series of ‘chapters’, Koya manipulates and alters the digital images to make thought-provoking collisions between cultures, particularly between his native Japan and the West. Abe has so skillfully manipulated his images that we are unaware which parts are ‘original’ and which parts are his ‘additions’. After Seba is based on Hiroshige’s 32nd station from the Tokaido series. The dark blue halo surrounding the moon indicates that Koya was aware of, and based his design on, the first edition of Hiroshige’s print. The halo was omitted from later editions.

Animism consists of 26 works and was Koya’s response to the Great Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami (11 March 2011). “My family has a long history in the area and the disaster was personal.”

Koya has digitally altered the images so as to remove almost every trace of human presence, as though humanity and its creations have been swept away.

“…a human being belongs to nature and is simply a product of nature. When a person dies, the person returns to nature: he becomes land. This is the circle…” -Koya Abe

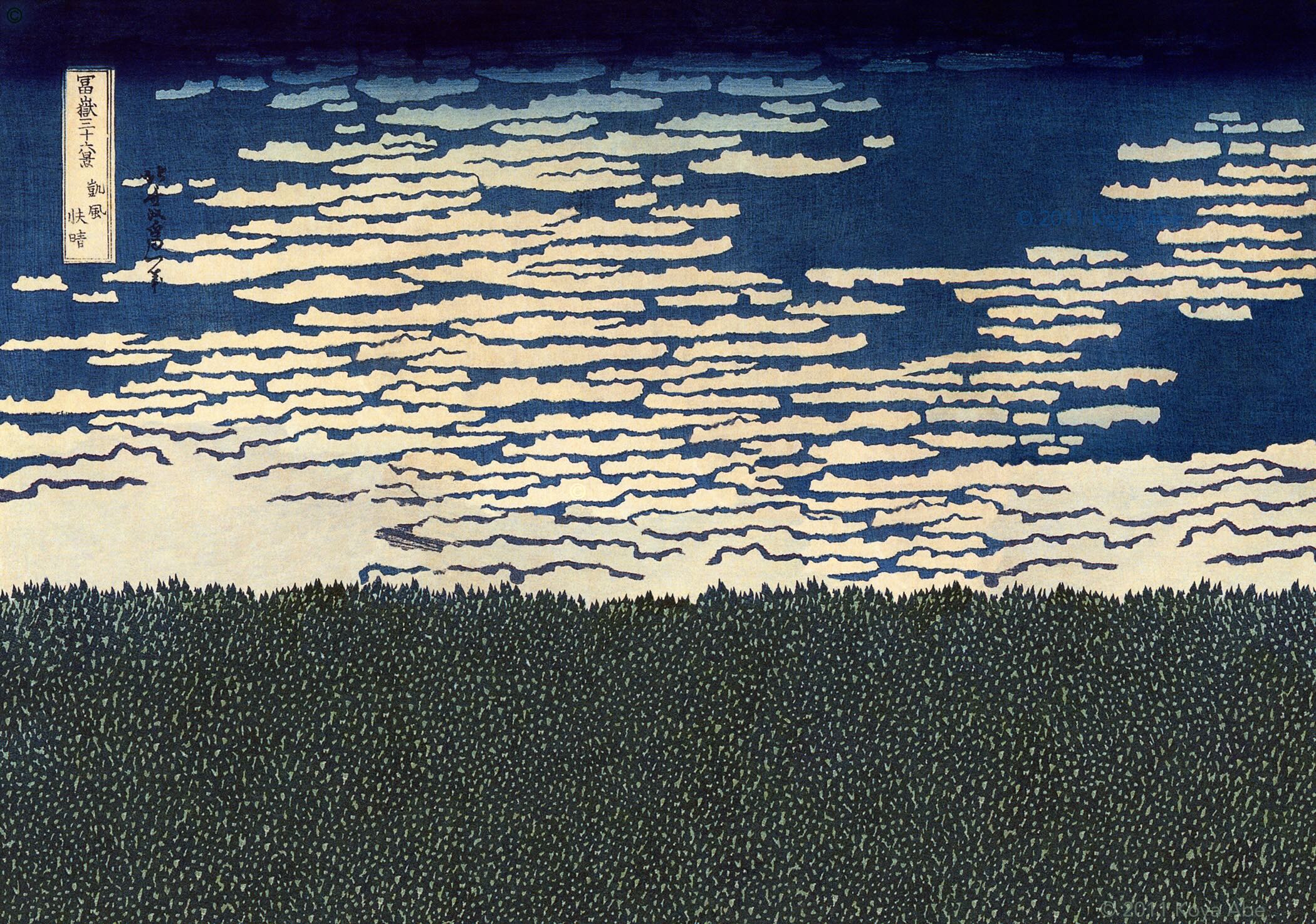

The series also includes motifs based on works by Hokusai. In After Red Fuji, even the most iconic (and geologically most immovable) symbol of Japan has disappeared, leaving the landscape deserted.

However, in another series Aesthetic(s) (2014), Koya has placed elegant women as taken from 1950-60s Western fashion illustrations in the classic landscapes of Hiroshige, creating anachronistic and humoristic scenes, where Japanese and Western culture meet (or clash). In Koya’s version of Hiroshige’s iconic snow scene of Kanbara at night, a 1960s girl fashionably dressed for winter is standing in the foreground looking straight at the viewer, while the Edo-period travellers unaware of her presence are trudging through the village covered in deep snow. This duality of cultures has been incorporated in most of Koya’s artwork from the beginning.

As Koya explains: “In essence, my background in studying photography as a Japanese person and as a foreigner in New York City lead me to the approach that I am exploring in my art. Ukiyo-e was and still is a core part of my work because of its personal context in my life. In my view, Hiroshige was the greatest photographer, before photography was invented.”

Hiroshige: artist of the open road at The British Museum will run until 7th September 2025. It is accompanied by a beautiful and well-researched catalogue written by Alfred Haft.

“I entrust my brush to that highway heading east, and seek journey’s end in the celebrated sights of a pure land in the west.” – Utagawa Hiroshige, poem written on his deathbed, 1858

This article is an original text of https://intojapanwaraku.com/art/278225/