Jewellery that avenges the death of the deceased master

Texts Sawada Toko

Those familiar with world history may be familiar with the ‘necklace incident’ that took place around Marie-Antoinette, the last queen of France. The year was 1785, on the eve of the French Revolution. A female impostor, who claimed to be a descendant of a noble family, approached a certain clergyman and swindled him out of money by falsely claiming to be a friend of Marie Antoinette. The necklace that gave the case its name was made by Louis XV, the grandfather of Marie-Antoinette’s husband, for his mistress, and was studded with more than 500 diamonds. After Louis XV’s sudden death, the necklace remained in the hands of a jeweller, and the conwoman made off with it after having a clergyman buy it for her, claiming that Marie-Antoinette wanted it.

The case soon became public and the female impostor was quickly arrested. However, the queen’s reputation was destroyed when she wrote a book full of lies about Marie-Antoinette while in prison. It is interesting to note that the fraud, which is an essential part of the history of the French Revolution, is inseparable from this magnificent piece of jewellery.

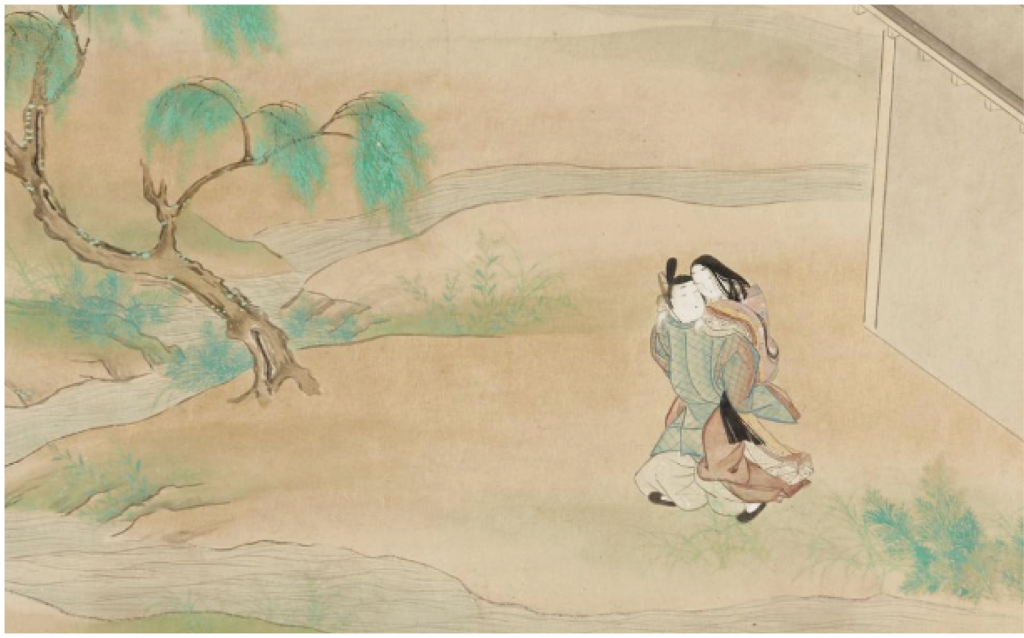

In fact, there are several examples of jewellery also being involved in the history of Japanese antiquity. For example, Emperor Nintoku, who is believed to have been buried in the Mozumimiharanaka no Misasagi (百舌鳥耳原中陵 : Sakai City, Osaka Prefecture), Japan’s largest zenpokouenfun (large keyhole shaped burial mound), was the country’s 16th emperor. He is thought to have existed around the late 4th century. According to the ‘Nihon Shoki (日本書紀)’, Japan’s oldest official history, one day Emperor Nintoku asked his half-brother, Prince Hayabusa wake no miko (隼別皇子), to act as his go-between, as he wished to take a woman named Metori no himemiko (雌鳥皇女) as his wife. Prince Hayabusa wake no miko, however, had the audacity to take Princess Metori no himemiko as his wife, and even procclaimed his ambitions for the throne. In the end, they were killed by assassins sent by Emperor Nintoku, but Princess Metori no himemiko was said to be wearing a magnificent piece of jewellery at the time of her death. One of the assassins steals the jewellery from the dead body of the Princess and gives it to his wife.

According to the ‘Nihon Shoki’, these jewellery items were ‘tedama’ and ‘ashidama’ – beads worn as decorations for the hands and feet, or, in modern terms, bracelets and anklets. The wife, who received the stolen jewels from her husband, apparently lent them to a woman close to her without knowing their origin. Later, at a banquet held at court, the emperor’s empress noticed that the jades worn by the women in attendance resembled those belonging to Princess Metori no himemiko. It is revealed that an assassin has stolen the hand and foot jewels of Princess Metori no himemiko, and he is condemned to death. It is as if her jewellery was an attempt to avenge the death of its deceased owner.

It shows that she wears bracelets on her wrists and anklets on her ankles. The extravagant attire and the fact that her entire body is neatly represented, down to her legs, and that she is seated on a chair, suggest that she represents a woman of very high status.

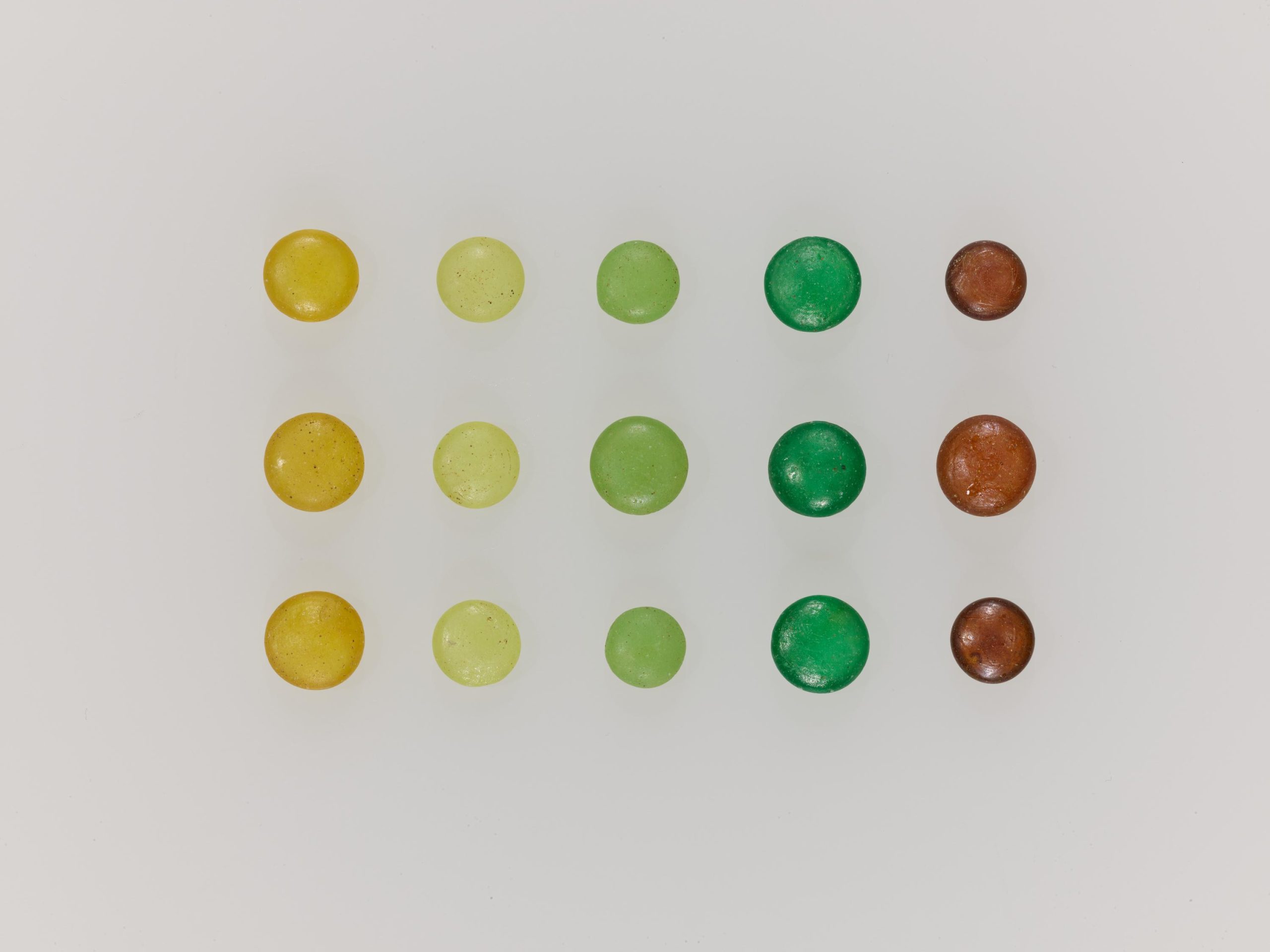

Only a very small handful of people

The Takaidayama kofun (高井田山古墳) mound in Kashiwara City, Osaka Prefecture, is a round burial mound dating from around the 5th century, close to the reign of Emperor Nintoku. Of the two coffins in which he was buried, the coffin on the west side had been stolen, but that on the east side had not, and pure gold ear rings were excavated from the position of both ears with the pillow to the north, and glass beads were found in clusters near both wrists and ankles. In other words, the dead were apparently buried wearing jewellery, including cueballs and anklets. According to the report, tedama and ashidama were both made of dark blue glass balls, but the average diameter of the balls used for the tedama was about 1 cm, while the ashidama were about 5 mm in diameter, which is very different. The glass products may sound heavy, but the total weight of the tedama is about 20 grams for one hand and less than 10 grams for one foot, so in terms of weight alone they are not much different from today’s bracelets and anklets.

A little later, in the ‘Harimakoku Fudoki (播磨国風土記)’, which was ordered to be compiled in the 6th year of Wado (713), an anecdote is recorded about women with jade ornaments on their hands when the Imperial Court captured a certain family. When an official, sensing something was amiss, enquired about their origins, the women were found to be of noble birth and were released. Here, the presence of cudgels is used as a standard to indicate the status of the women, suggesting that tedama and ashidama were only worn by a handful of people at the time.

Ashidama mo tedama mo yurani oru hatawo Kimiga Mikeshi ni nui aemu kamo(足玉も手玉もゆらに織る服を 君が御衣に縫ひもあへむかも(『万葉集』)

——I wove it into cloth with all my heart, shaking my toadstools and cueballs violently. I wonder if I can make this into a kimono that will suit her. ‘Manyosyu’

‘Yurani’ is an expression of the sound made by balls touching each other.

Can you sew and dress your robe with cloth woven with the sound of tedama and ashidama?

In this song, the sound of the glass balls touching each other and the sparkle of the sound can be clearly perceived.

By the way, five generations after the aforementioned Emperor Nintoku, there was a woman named Sahobime (沙本毘売) who was the empress of Emperor Suinin, who is thought to have existed from the late third to the fourth century. According to the ‘Kojiki (古事記)’, a history book on the same level as the ‘Nihonshoki’, on one occasion, Sahobime’s elder brother attempted to have her sister killed, in an act of treason. However, Sahobime, who loved the Emperor, was unable to complete the assassination and confessed everything to him, before running to her brother. However, at the time, a child of the Emperor was in her womb. She eventually wanted to deliver the child to the Emperor, but not wanting the Empress to die, the Emperor took the opportunity to plan to forcibly take her away. Knowing the Emperor’s intentions in advance, Sahobime shaved off her long hair and put on a wig, and spoiled the threads of her tedama and her robe with sake before handing the child over to him. After the soldier, who boasted of his strength at the Emperor’s behest, received the baby, he reached out to catch her, only to have her hair fall out at the edge of his grip, the thread of her cue ball break if he grasped it, and her robe tear if he tried to hold it. It is interesting to note that here she deliberately devised a way to cut the thread of the tedama.

Ancient glass has more air bubbles than today’s glass, and the texture of excavated objects is often rough to the touch. Since they were strung together and used as bracelets, the threads that penetrated the jade must have been quite strong. That is why the soldiers who came to capture Sahobime probably tried to grab the tedama, and the ingenuity they applied to it caught him off guard.

Today, the word tedama has been forgotten, replaced by the French word ‘bracelet’. However, if you peruse the old books, you will find that in the distant past, tedama were used by women to protect themselves, or to avenge their sins. As well as their beauty, jewellery also tells the story of the lives of those who loved it.

Although they date from the Nara period, it is easy to imagine that they attracted the attention of many people. The tedama and ashidama, made from a series of these, were only worn by a handful of people at the time.

Sawada Toko

Born 1977, Kyoto. Graduated from Doshisha University, Faculty of Literature, and completed the Master’s course at the same university. She made her debut in 2010 with ‘Koyo no Ten(孤鷹の天)’, which won the Nakayama Yoshihide Literature Award(中山義秀文学賞); won the Shinran Prize(親鸞賞) in 2016 for ‘Jakuchu(若冲)’ and the 165th Naoki Prize in 2021 for ‘Hoshi Ochite, Nao(星落ちて、なお)’.

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/225740/