As one of Japan’s most popular artists around the world, 葛飾北斎 (Katsushika Hokusai, 1760-1849), helped formulate the image of Japan and Japanese art for many foreigners, particularly in the late 19th century. In this series, we take a look at several motifs featured in Hokusai’s artwork that exemplify the beauty of Japan. In this article, we focus on the theme of water.

Prints of water show Hokusai at his best—from waterfalls to the ocean, there was nothing Hokusai couldn’t draw!

Japan—a country blessed with an abundance of water. Thanks to this fact, Hokusai was able to develop his spectacular, almost transcendental splashing wave designs.

One could say that another symbol of Japanese beauty often drawn by Hokusai is water. Japan runs rich with waterways and is dotted with many famous waterfalls. Before long these winding rivers pour into the ocean that surrounds the island country. If you think about it, there aren’t as many lands as abundant with water as Japan. Hokusai was aware of this reality and armed with the belief that there was nothing he could not draw, the artist set out to draw and vividly express a moment of the very difficult-to-capture subject, moving water.

From long before, Japanese artists have taken great pains to devise an idealized form of water. Starting with what is rumored as the original example of Japanese aesthetics, the National Treasure 「那智瀧図」 (“Nachi Falls”), there have been many pictures throughout Japanese art history featuring water as their subjects. However, we have yet to find anyone as obsessed with water or who depicted water in its ever-changing and infinite variety of forms as Hokusai. From crashing waves on rough seas, to his keen observation of falling streams, to even producing an image not unlike a video still in its realism, there truly wasn’t anything Hokusai could not draw. We want to call this genius 浮世絵 (ukiyo-e, a genre of commoner art from the 17th to 19th century depicting everyday life) artist a visual magician!

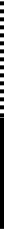

『上町祭屋たい天井絵 男浪図』 (Kanmachi Festival Float Ceiling Painting “Masculine Waves”), single panel, colored pigment on paulownia wood, 118.0 × 118.5 cm, 1845 – 46, Hokusai Museum.

『上町祭屋たい天井絵 男浪図』 (Kanmachi Festival Float Ceiling Painting “Masculine Waves”), single panel, colored pigment on paulownia wood, 118.0 × 118.5 cm, 1845 – 46, Hokusai Museum.

Comparatively early in his career as a painter between 1800 – 1805, Katsushika Hokusai designed the print 「おしをくりはとうつうせんのづ」 (“Express Delivery Boats Rowing through Waves”). If we count this as the starting point for when Hokusai began trying to express the tossing and crashing of waves, the peak of his efforts would be the magnificent waves featured in 「神奈川沖浪裏」 (“The Great Wave off Kanagawa”) (1830 – 1833) from 『富嶽三十六景』 (Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji) series. This image here represents the culmination of his skills in his final years. Furiously tumbling and swirling with intense energy, these waves appear to have been painted by some angry god or demon. In his quest to capture the essence of waves, Hokusai seems to have envisioned something out of this world. He painted the festival float ceiling painting pictured above at the age of eighty-six during his second visit to the town of Obuse in the Shinshū region of present Nagano prefecture.

Other examples

『千絵の海 総州銚子』 (“Rough Water at Chōshi” from the Sea of Chie series), medium format polychrome woodblock print, c.1833. Image: UIG/Pacific Press Service

『千絵の海 総州銚子』 (“Rough Water at Chōshi” from the Sea of Chie series), medium format polychrome woodblock print, c.1833. Image: UIG/Pacific Press Service

The series 『千絵の海』 (Sea of Chie) consists of 10 prints that depict different fishing styles throughout various locations in Japan, but the landscape pictures also express different types of waves and movement of water. This highly-regarded print from the series is often called a masterpiece and illustrates the fishing customs of Chōshi, an area known for its powerful waves from the Pacific. A receding wave sharply pulls back along rocks in the foreground, while an incoming wave rushes forward towards the rocks in the background. The opposing waters collide in the center with tossing white spray and foam. This volatile and dynamic composition draws viewers in and gives the impression of being swallowed up by the wild waves.

『富嶽三十六景 甲州石班沢』 (“Kajikazawa in Kai Province” from The Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series), oban-size polychrome woodblock print, c.1831, the Sumida Hokusai Museum.

『富嶽三十六景 甲州石班沢』 (“Kajikazawa in Kai Province” from The Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series), oban-size polychrome woodblock print, c.1831, the Sumida Hokusai Museum.

The Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series is known for its bold and original compositions, but this print from the series is particularly known for its feeling of tension. The setting depicts what was formerly Kajikazawa in Kai Province and is presently known as Fujikawa in Yamanashi prefecture. The Kamanashi River and Fuefuki River converge into the large Fuji River, making this area an important strategic point for transportation. Kajikazawa was known for its strong current and rapids, and indeed at first glance, this print seems to depict the tossing waves of an ocean rather than a river. The figures of fishermen perched atop the dark indigo colored rock made from Berlin blue ink is particularly impressive.

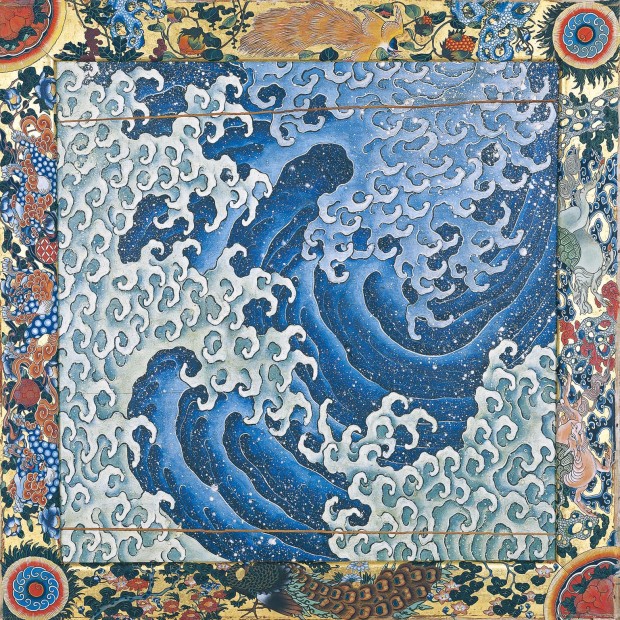

『諸国瀧廻り 下野黒髪山きりふりの滝』 (“Kirifuri Waterfall at Kurokami Mountain in Shimotsuke” in the series, A Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces), oban-sized polychrome woodblock print, c. 1832-33, the Sumida Hokusai Museum.

『諸国瀧廻り 下野黒髪山きりふりの滝』 (“Kirifuri Waterfall at Kurokami Mountain in Shimotsuke” in the series, A Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces), oban-sized polychrome woodblock print, c. 1832-33, the Sumida Hokusai Museum.

Hokusai’s 『諸国瀧廻り』 (A Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces) series enjoyed the same popularity as his Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series. While both series feature impressive landscapes, it is said that in his waterfall series, Hokusai’s main aim and passion was to study and portray the way water changes as it falls. In this particularly magnificent print, Hokusai beautifully depicts the changing form of the stream as it pours down from the rocks and splashes into the basin below, creating wavelets. The formative style seen here is very Hokusai-like. Drawn here is Kirifuri Waterfall, one of the Nikko region’s top 3 waterfalls, on Kurokami Mountain also called Mount Nandai.

Translated and adapted by Jennifer Myers.