In Japan, the new year is particularly a time when people engage in culture and traditions. Many of the traditions passed down through generations can be traced back as far as the Heian period. As we revisit scenes from the historical drama ‘Hikaru Kimi-e (光る君へ)’, set in the Heian era, let us explore traces of the time when figures such as Fujiwara no Michinaga (藤原道長) and Murasaki Shikibu (紫式部) were alive, preserved within New Year traditions.

Is the origin of hanetsuki a nobleman’s sport?

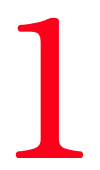

In the early episodes of ‘Hikaru Kimi-e’, noblemen were seen gallantly riding horses and competing in a sport called dakyu (打球). It bore a striking resemblance to polo in England, didn’t it?

In Japan, this dakyu eventually evolved into a children’s game called ‘buriburi-giccho (ぶりぶり毬杖)’, where a ball was hit back and forth using a wooden mallet attached to a string. It is said that this game later became the foundation for hanetsuki (羽根突き), a game similar to badminton, played with a wooden paddle and without a net.

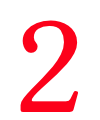

Hamayumi and Hamaya: bows and arrows to ward off evil

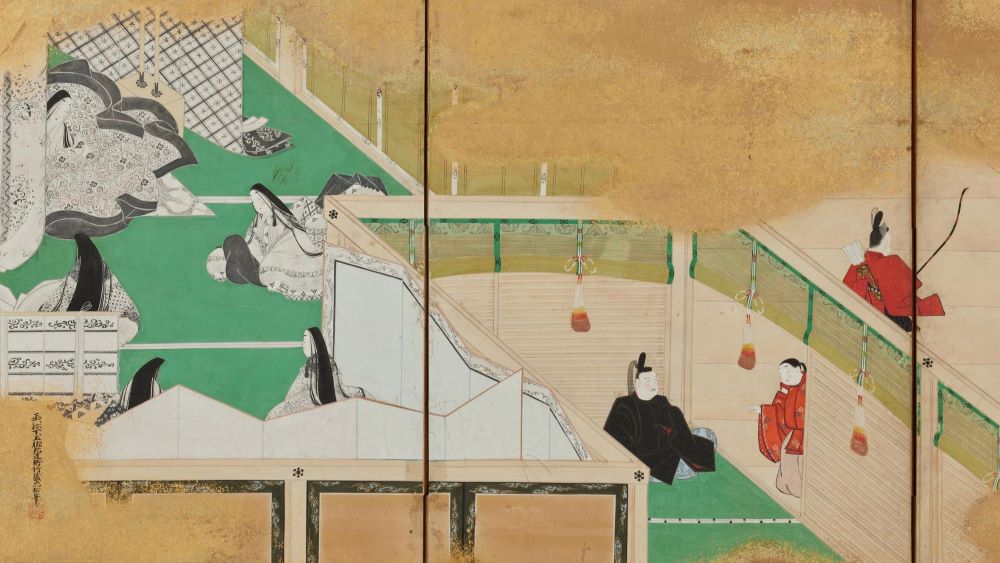

The hamayumi (破魔弓, ceremonial bow) displayed during a boy’s first New Year, and the hamaya (破魔矢, ceremonial arrow) often received at shrines, are believed to originate from the New Year’s court ritual of the Heian period known as ‘jarai (射礼, archery etiquette)’.

Over time, this ritual evolved into an event where children would shoot arrows at targets as a form of fortune telling. The target came to be called ‘hama (ハマ)’, and the characters for ‘破魔 (warding off evil)’ were applied, transforming the practice into a ritual to ward of evils.

Since ancient times, bows and arrows have been regarded as tools to ward off evils. Practices such as tsuru-uchi (弦打, striking the bowstring) and meigen (鳴弦, resonating the bowstring) were common during significant events, such as the birth of a prince or rituals following a birth.

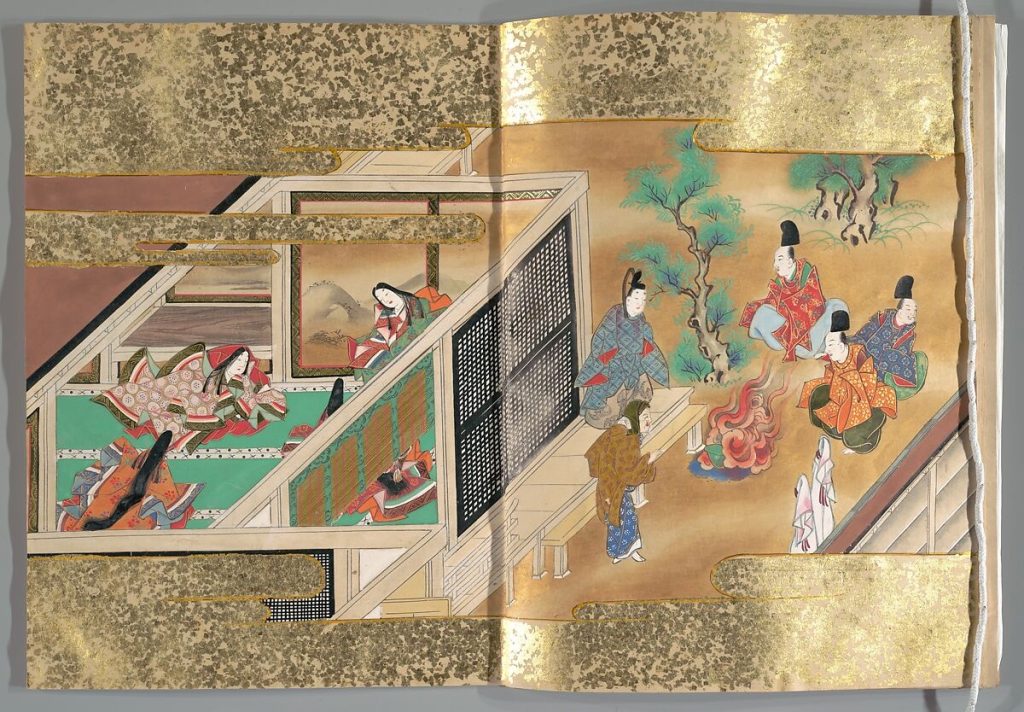

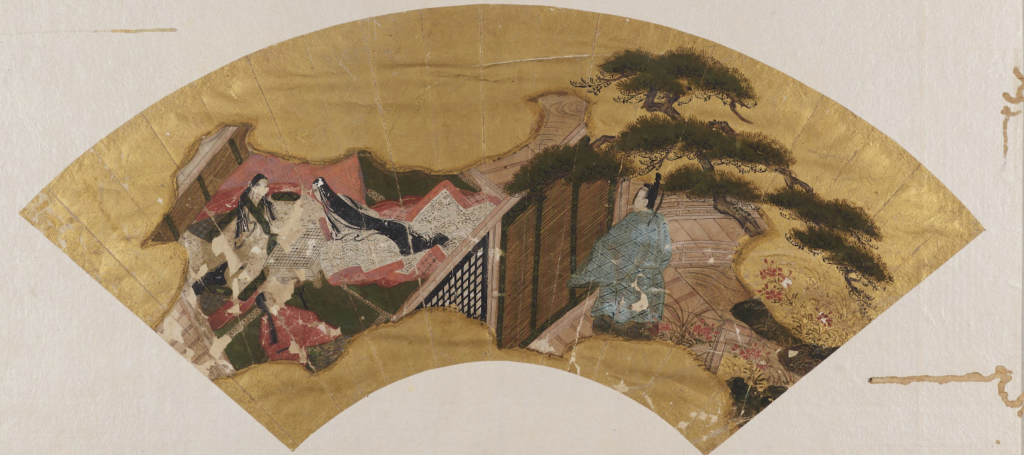

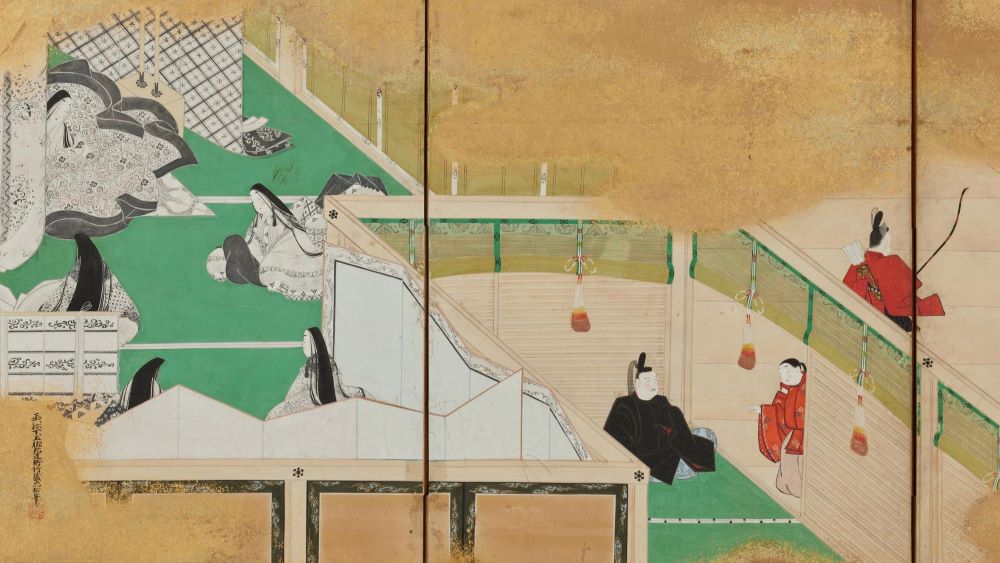

The ‘Eiga monogatari zu byobu (栄華物語図屏風, Folding screen illustrated with the ‘tale of glory’)’, which depicts the birth of Empress Shoshi (彰子), consort of Emperor Ichijo (一条), includes an illustration of a man holding a bow, further highlighting the tradition’s deep historical roots.

In ‘Hikaru Kimi-e’, during the scene depicting Empress Teishi (定子) ’s childbirth, her brothers, Korechika (伊周) and Takaie (隆家), stood watch through the night, bows in hand. Similarly, in the scene of Shoshi (彰子) ’s childbirth, noblemen lined up to perform tsuru-uchi, but malevolent spirits wreaked havoc during the ritual. While Michinaga (道長) is portrayed in the drama as an earnest and upright figure, the fact that he was so deeply resented by others suggests… well, quite a lot, doesn’t it?

The origins of karuta games lie in kai-awase

Karuta (かるた, traditional Japanese playing card game), such as Hyakunin Isshu (百人一首) Karuta, Inubou (犬棒) Karuta, and Kyodo (郷土) Karuta, are now a staple of New Year celebrations, with various types available today.

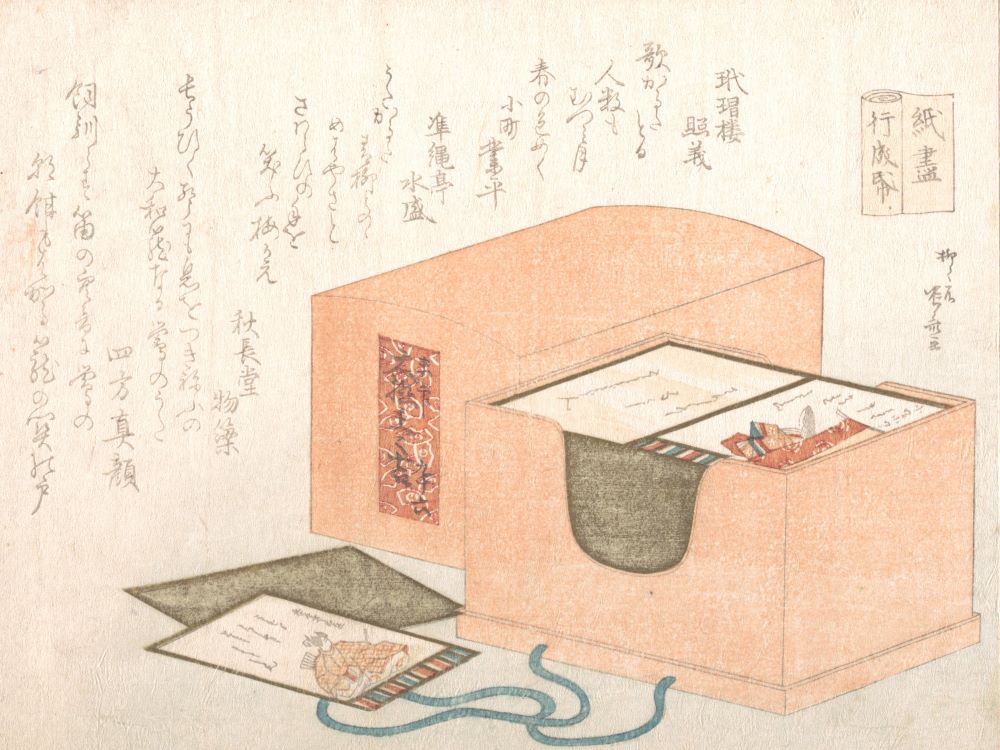

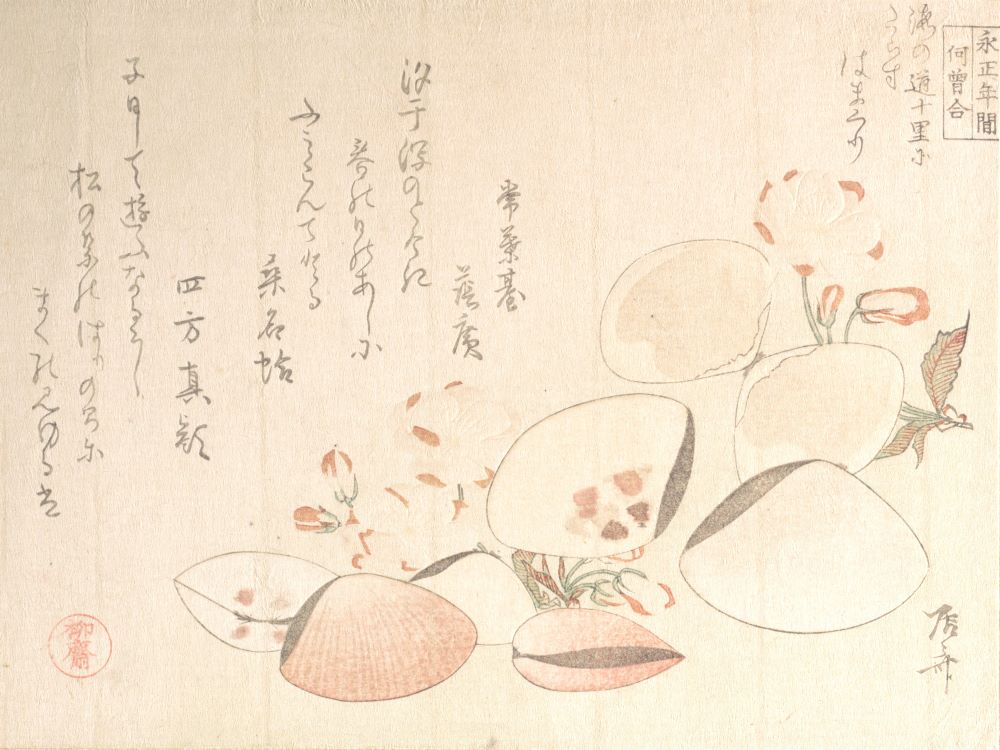

The roots of karuta trace back to the Heian period and the aristocratic pastime known as kaioi (貝覆い), more commonly referred to as kai-awase (貝合わせ). In this game, pairs of clam shells, such as those from hamaguri clams, were scattered, and players competed to find the perfect match based on the patterns or sizes of the shells.*

Over time, the insides of the shells began to feature matching paintings of flowers and birds, scenes from The Tale of Genji, or waka poetry. This evolution ultimately gave rise to the karuta games we know today.

*Originally, kai-awase was a game where players competed for the size and beauty of the shells. Later, the term also came to refer to the matching game of kaioi, where players searched for perfectly paired shells.

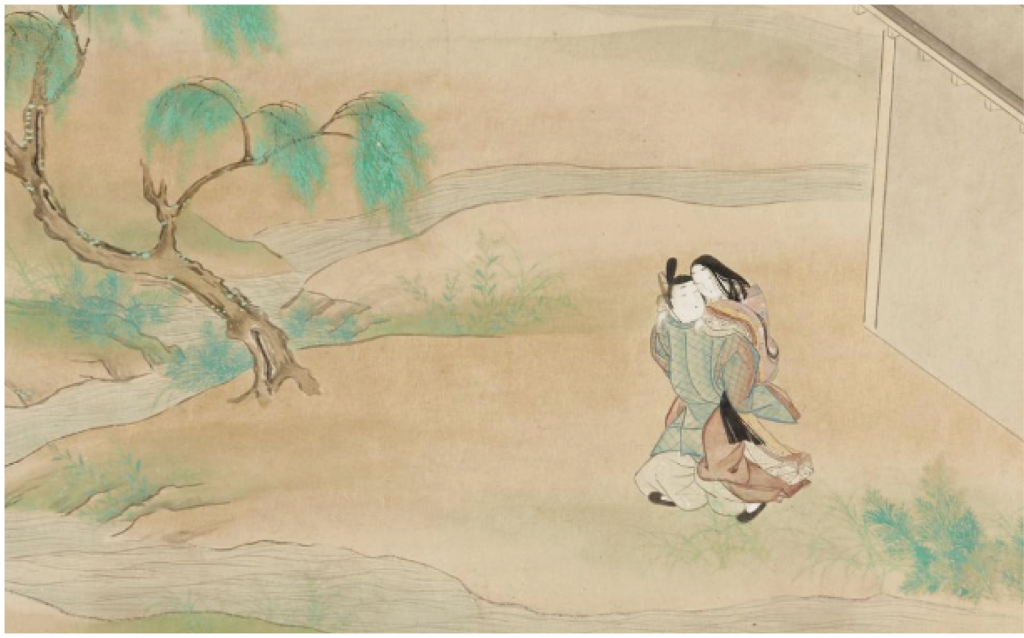

In ‘Hikaru Kimi-e’, there was a poignant scene where the young Shoshi, newly introduced to Emperor Ichijo’s court, played with shells in solitude.

After the birth of a prince to the couple, Shoshi was later shown smiling warmly as her attendants, including Izumi Shikibu (和泉式部), and noblemen enjoyed a lively game with beautifully decorated shells arranged in the garden.

‘Otoshidama’ – a gift shared from the toshigami

The setting of ‘Hikaru Kimi-e’ takes place during the height of the regency politics era, when maternal relatives of the Emperor served as regents or chancellors to wield political power. Emperor Ichijo ascended the throne at the age of seven, and Shoshi entered the imperial court at just twelve, all to ensure the regent family maintained their dominance.

In those days, the traditional kazoedoshi (数え年) age system meant that a child’s first year began at birth, and a year was added every New Year’s Day. By today’s age-counting methods, they were effectively one to two years younger.

During the New Year, it is the Toshigami (年神, deity of the year) who bestows upon us the gift of a new year of life (spirit). ‘Otoshidama (お年玉)’ is a gift received from the Toshigami, symbolising life itself. In the past, the rice cakes offered to the Toshigami were later shared among family members, and these were called ‘otoshidama.’ Today, the pocket money that children receive during the New Year is a remnant of this tradition.

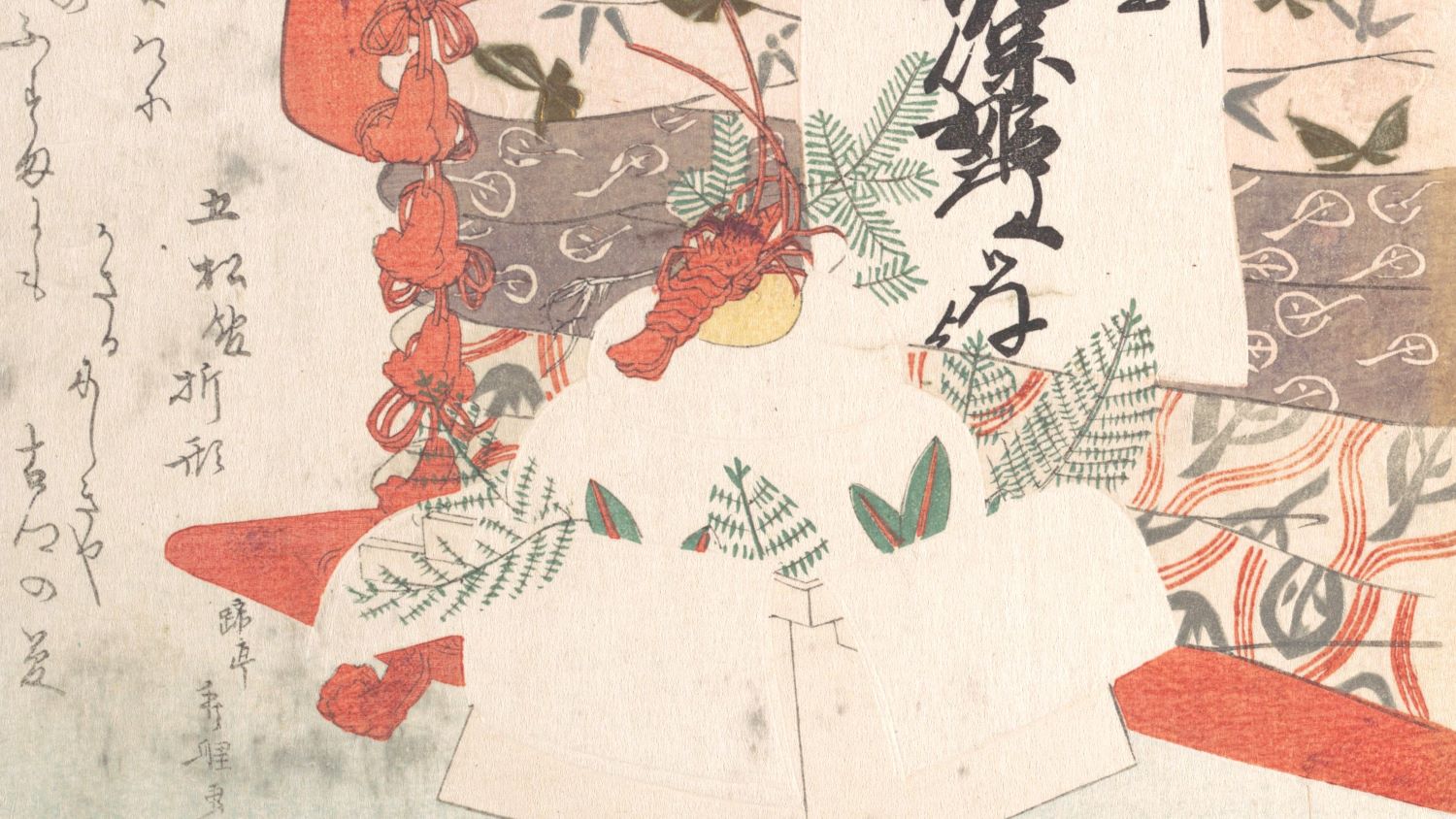

‘Pine’ – a symbol of eternity

The pine tree, which retains its green leaves even in winter, symbolises eternal life and youth. Since the Heian period, pine trees have been used as markers to welcome the Toshigami during the New Year celebrations.

Court rituals eventually transformed into public celebrations and children’s games…

Though the forms may have changed over time, the hope for the safety of families and the healthy growth of children remains unchanged, both now and in the past.

Thinking about how familiar New Year traditions have been passed down from the Heian period to the present day, it almost feels as if I’ve crossed time and space to meet Murasaki Shikibu herself.

Reference Books:

Ocho no katachi (王朝のかたち), written by Inokuma Kaneki (猪熊兼樹), Hayashi Mikiko (林美木子) and yushoku saishoku (有職彩色, illustrated with traditional colours), Tanko-sha (淡交社)

Encyclopedia Nipponica, Shogakukan (小学館)

The Dictionary of Japanese History, Yoshikawa Kobunkan (吉川弘文館)

Revised Edition of the Great Encyclopedia of the World, Heibonsha (平凡社)

The Complete Works of Japanese Classical Literature: Eiga Monogatari (栄花物語), Shogakukan (小学館)

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/rock/culture-rock/260340/