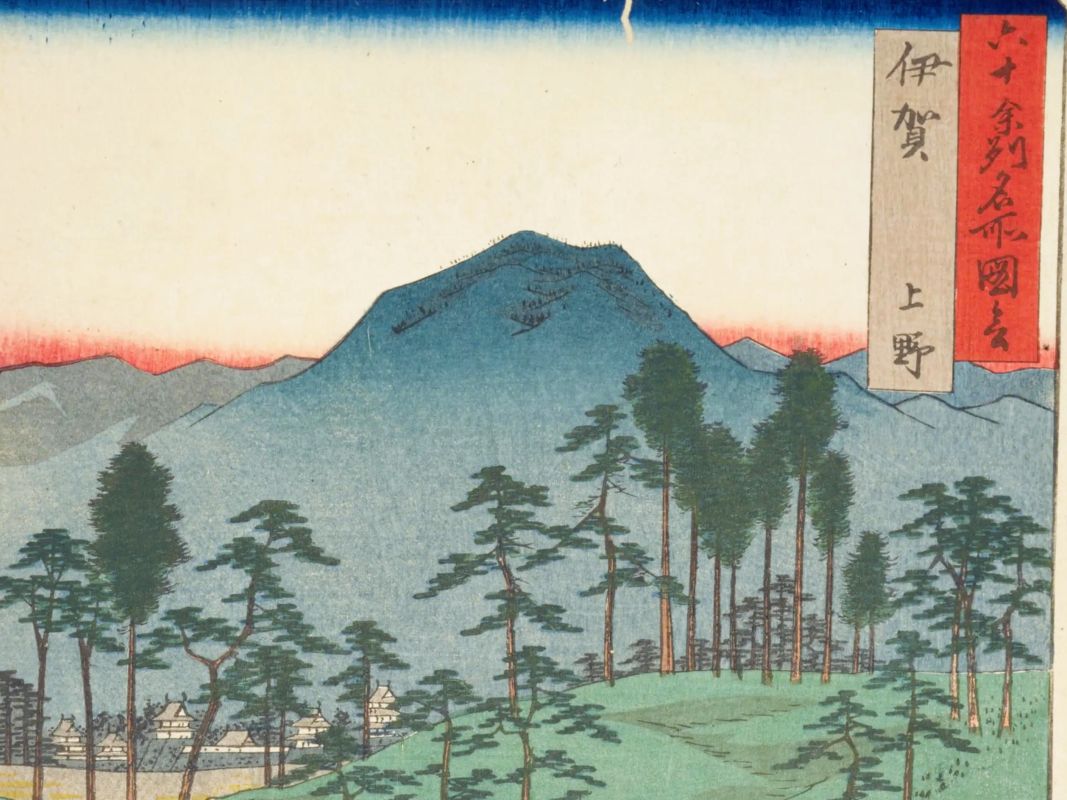

Among those tasked with security was a group known as the ‘Igamono (伊賀者),’ said to have rescued Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康) from a perilous situation during the Sengoku (戦国) period. The Igamono were ninjas (忍者) originating from Iga (伊賀) Province (Iga no Kuni, modern-day western Mie Prefecture), familiar from popular media such as the manga series Ninja Hattori-kun (忍者ハットリくん).

The igamono of the Ooku: watchmen and bodyguards

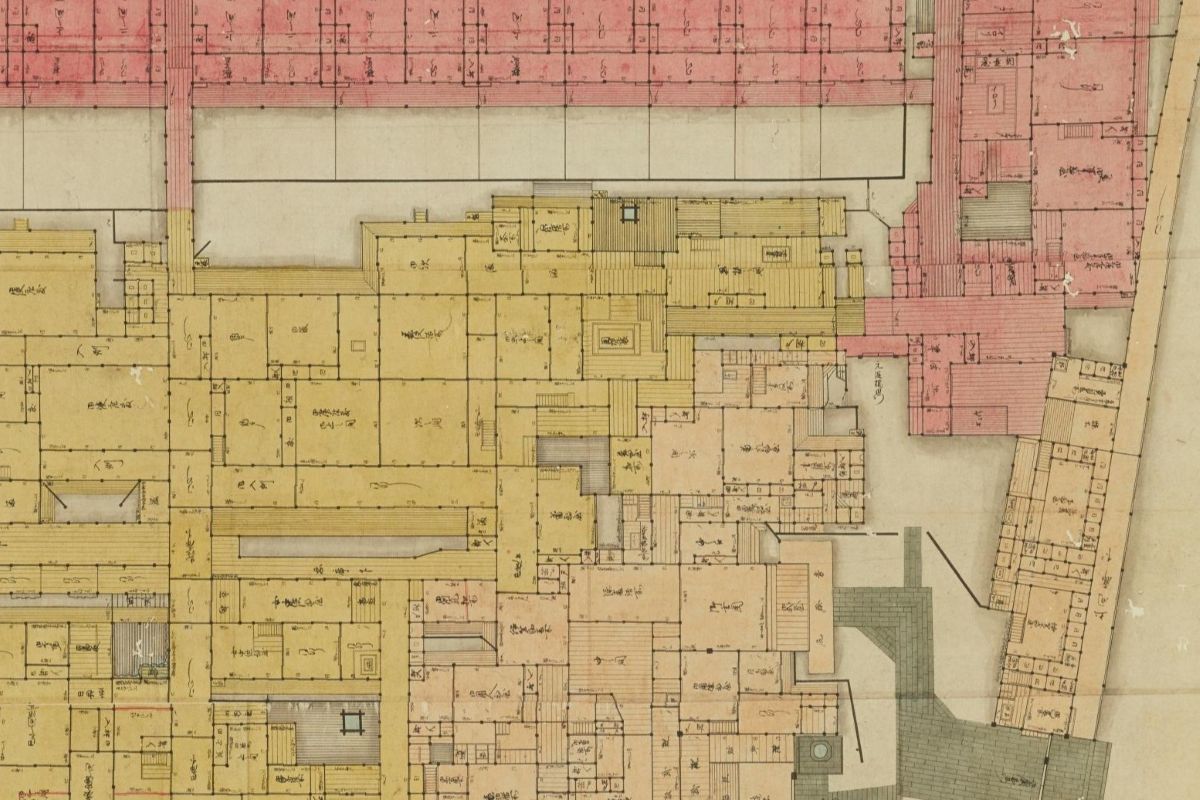

The Ooku was divided into three main sections: the Gotenmuki (御殿向), where the Midaidokoro (御台所; the Shogun’s official wife) and concubines who bore the Shogun’s children resided; the Nagatsubone (長局), where the Ooku ladies-in-waiting lived; and the Ohiroshiki-muki (御広敷向), where male officials worked.

The Ohiroshiki-ban (御広敷番) were responsible for monitoring the people and goods entering and exiting the Ooku. Working under the management of the Ohiroshiki-ban no Koshira (御広敷番之頭; head of the Ohiroshiki-ban), the guards were divided into roles such as Ohiroshiki Soeban (御広敷添番) and Ohiroshiki Igamono (御広敷伊賀者). The Ohiroshiki Igamono guarded the Nanatsuguchi (七つ口), a connecting gate between the Nagatsubone and the Ohiroshiki. They also escorted the ladies-in-waiting when they left the Ooku.

The Shogunate’s retained igamono were snipers

The Igamono did not only work in the Ooku.

The Teppo Hyakuningumi (鉄砲百人組, Musket Hundred-Man Units) that protected the castle consisted of four divisions: the Iga group, Koka (甲賀) group, Negoro (根来) group, and Nijugokigumi (二十五騎組). They usually took turns guarding the Hyakuninbansho (百人番所, hundred-man guard station) in the Ninomaru (二の丸), protecting the Ote San no Mon (大手三の門, Ote Third Gate). This gate was the second gate after entering the Otemon (大手門), located between the Sannomaru (三の丸) and Ninomaru areas. Daimyo (大名, feudal lords) entering the castle had to dismount from their palanquins here to proceed, so the gate was also known as the Gejomon (下乗門, Dismount Gate).

The Igamono were also responsible for guarding the Shogun during his visits to Kan’ei-ji (寛永寺) Temple in Ueno (上野) and Zojo-ji (増上寺) Temple in Shiba (芝, both ancestral temples of the Tokugawa family). It is said that in times of emergency, their duty was to protect the Koshu Kaido (甲州街道) and assist the Shogun’s escape from Edo.

The Igamono’s status was relatively low within the samurai class, equivalent to Yoriki (与力) or Doshin (同心, low-ranking officials). They were Gokenin (御家人, direct retainers) classified as Ome-mie ika (御目見え以下), meaning they were not permitted a direct audience with the Shogun. Despite this, there was a specific reason why they were entrusted with such crucial duties.

Saving Ieyasu during the Crossing of Iga crisis

The ‘Iga-goe’ (伊賀越え, Crossing of Iga) is counted as one of the most significant crises in Tokugawa Ieyasu’s life. In Tensho (天正) 10 (1582), when Oda Nobunaga (織田信長) was assassinated in the Honno-ji (本能寺) Incident, Ieyasu was in Sakai (堺), Izumi (和泉) Province (modern-day Sakai City, Osaka Prefecture), having been invited by Nobunaga.

Having lost his ally Nobunaga and accompanied by only a few retainers, Ieyasu was pursued by Akechi Mitsuhide (明智光秀) and at one point prepared for death. However, his retainers persuaded him to cross the mountains of Iga, aiming to return to his territory in Mikawa (三河) Province.

It was during this time that local samurai from Iga Province and Koga (甲賀, Omi (近江) Province), separated by the mountains, assisted Ieyasu in crossing the region. Some of these individuals, who excelled in intelligence gathering and surprise attacks during the Sengoku period, subsequently served Ieyasu and later became retained officials of the Shogunate.

However, some historians suggest that the episode where the Igamono helped Ieyasu during the ‘Crossing of Iga’ might be a later fabrication.

Hattori Hanzo was a samurai, not a ninja

Interestingly, Hattori Hanzo Masanari (服部半蔵正成), who is widely perceived as the ‘leader of the Iga ninja,’ was actually a samurai counted among Ieyasu’s sixteen close retainers. While he commanded the Igamono, he himself was not a ninja.

Hattori Hanzo supported Ieyasu in his unification of Japan. During the Edo period, he established a residence in front of a gate facing the Koshu Kaido and guarded the western side of the castle. It is believed that this is why the gate became known as the Hanzomon (半蔵門).

The Igamono of the Ooku were a little arrogant

During the Edo period, a time of peace lasting 260 years, the ‘Igamono’ of the Ooku were no longer ninjas but had become conventional government officials.

The Igamono were inherently low-ranking samurai who were typically not permitted to wear hakama (袴). However, Ohiroshiki Igamono were specially allowed to wear haori (羽織) and hakama—a privilege granted specifically because of their duty in the Ooku.

When high-ranking individuals, such as the Roju (老中, Council of Elders), visited the Ooku, both the Ohiroshiki Soeban and the Igamono would line up in front of their guard stations and bow. During winter, hibachi (火鉢, braziers) were used in the guard stations, and it was customary to put them away before lining up. While the Soeban would put their braziers away, the Igamono did not.

Although both the Soeban and the Igamono were classified as Ome-mie ika (below the rank for an audience with the Shogun), the Igamono received significantly less pay from the Shogunate (30 hyo (俵) and two-person provision, roughly 15 koku (石)) compared to the Soeban (100 hyo, roughly 40 koku).

Despite their lower pay, the Igamono were allowed to keep their braziers out because of an anecdote from the early Edo period. A woman named Mika-dono (みか殿), a concubine of Ieyasu, noticed the Igamono on duty at the entrance on a cold winter day and kindly gave them a brazier.

This suggests that in the early Edo period, the Igamono assigned to Ooku security were older, seasoned veterans—elderly individuals who would have been considered in need of warmth. It seems they received slightly special treatment.

Perhaps Ieyasu had indeed been assisted by the Igamono at some point and never forgot that debt of gratitude.

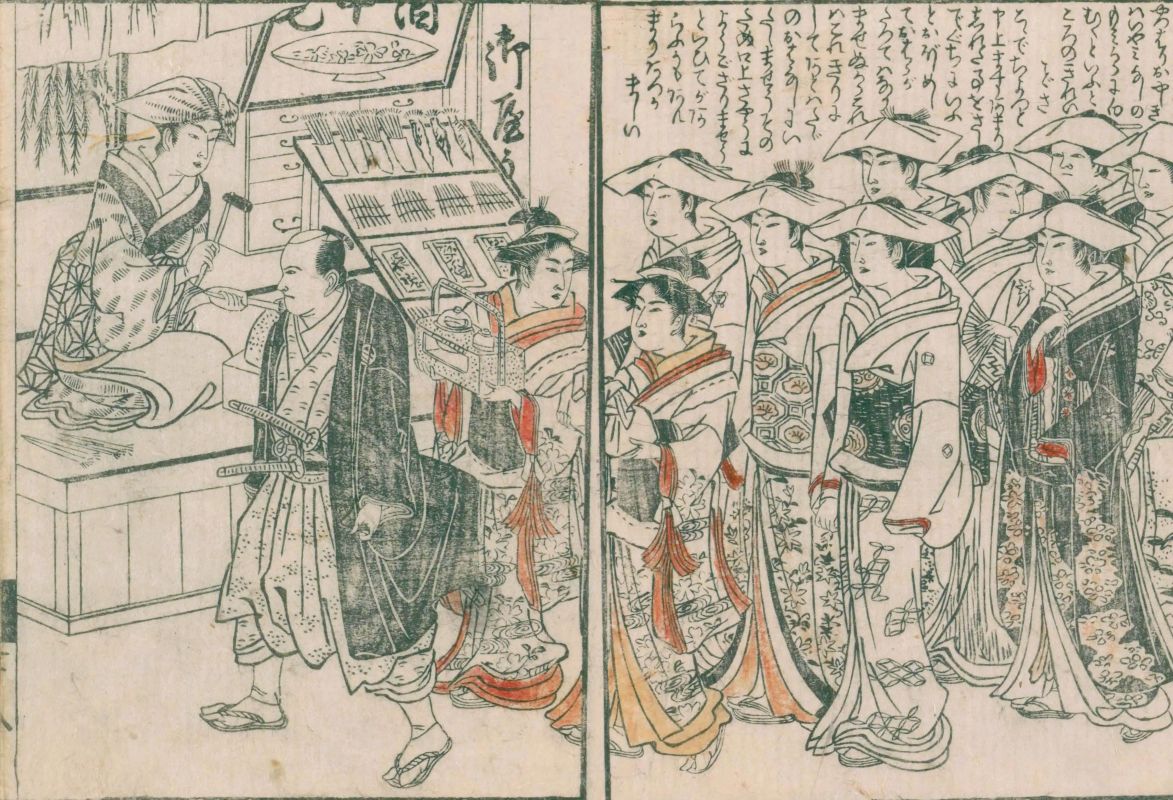

Header image: Cropped from Tsubone Masaoka, Nikki Danjo, Otoko no Suke, Kawazu Saburo, Matano Goro, Kisegawa, Shobu-mae, Yorimasa, Ino Hayata (局政岡・仁木弾正・男之助・河津三郎・股野五郎・き世川・菖蒲前・頼政・井ノ隼太) by Utagawa Toyokuni (歌川豊国). Source: National Diet Library Digital Collections

Descendants of the Ninja, by Takao Yoshiki (高尾善希)(Kadokawa Shoten, 角川書店)

Secret Agents and Garden Inspectors of the Edo Period, by Shimizu Noboru (清水昇) (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 河出書房新社)

The Ladies of the Inner Palace, by Mitamura Engyo (三田村鳶魚) (Seiabo, 青蛙房)

Nipponica: The Encyclopaedia of Japan (Shogakukan, 小学館)

The Dictionary of National History (Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 吉川弘文館)

World Encyclopaedia, Revised New Edition (Heibonsha, 平凡社)

Tales of Edo Castle (Tokyo Municipal Hibiya Library, 東京市立日比谷図書館)

Okazaki (岡崎) City History, Supplementary Middle Volume: Tokugawa Ieyasu and His Circle (City of Okazaki)

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/276455/