Woodblock prints spark travel fever in old Tokyo

In the early 1800s, two immensely popular series, Katsushika Hokusai’s 『富嶽三十六景』 (Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji) and Juppensha Ikku’s comic novel “Tokaidochu Hizakurige,” filled many hearts with a yearning to travel along the setting of these works. That is, the Tokaido Road which connected 江戸 (Edo, 1603-1868, present day Tokyo) with the ancient capital of Kyoto.

It was at this opportune time that 歌川広重 (Utagawa Hiroshige, 1797-1858) published 『東海道五十三次』 (The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido), an 浮世絵 (ukiyo-e, “pictures of the floating world”) series that enjoyed brisk sales, even rivaling those of Hokusai’s art. With this tour de force, Hiroshige turned landscapes into a mainstream genre of ukiyo-e and instantly joined the ranks of the era’s star artists.

『名所江戸百景 堀切の花菖蒲』 (One Hundred Famous Views of Edo: “Horikiri Iris Garden”)

Large-sized polychrome print, 1857, Nara Prefectural Museum of Art.

Large-sized polychrome print, 1857, Nara Prefectural Museum of Art.

Horikiri was a low-lying wetland fed by a side stream of the Sumida River, located in the northern corner of Tokyo’s Mukojima district. Every May, the whole area would burst into color with the blossoming of countless irises, making for a pleasant outing for Edoites. In this work, Hiroshige fills the foreground with a close-up of Horikiri’s famed irises, beyond which can be seen people taking in the beautiful display. The low angle of this perspective imparts a spacious feel to the scene.

Who is the Japanese artist, Utagawa Hiroshige?

In contrast with his predominantly eccentric, artsy peers, Hiroshige was a very serious, commonsensical man whose warmth is felt in his distinctive compositions crafted from painstaking observation of his subjects.

In his twilight years, however, Hiroshige’s personality seems to have changed, judging from the daring, pop art-like compositions that characterized many of the ukiyo-e produced for his swan song, 『名所江戸百景』 (One Hundred Famous Views of Edo), as exemplified by the three selections shown here, in this article.

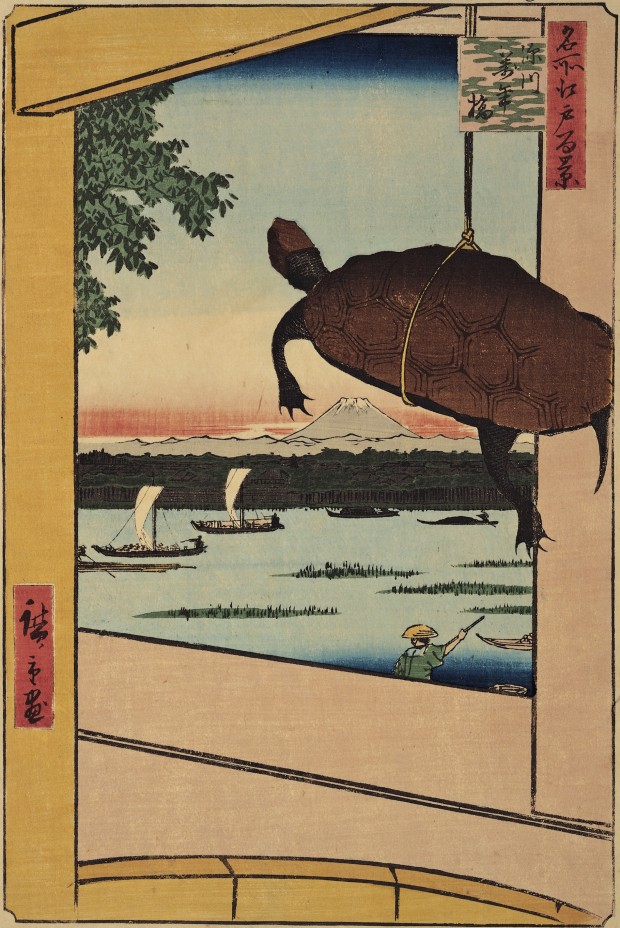

『名所江戸百景 深川萬年橋』 (One Hundred Famous Views of Edo: “Mannen Bridge in Fukagawa”)

Large-sized polychrome print, 1857, Nara Prefectural Museum of Art.

Large-sized polychrome print, 1857, Nara Prefectural Museum of Art.

Seemingly floating in midair, this turtle is actually suspended from the handle of a bucket, and is a play on the name of the titular bridge, as turtles were symbols of longevity figuratively said to live for 10,000 years. In Japanese, 10,000 years is pronounced as mannen. Captured turtles were used in the hojoe rite of Tomioka Hachiman-gu Shrine, in which turtles and fish were released back into the river in hopes of building up good karma. The turtle here forms an interesting contrast with Mt. Fuji, seen from across the Sumida River.

As suggested by the emphasis placed on the foreground objects in these three images, Hiroshige seems to have been influenced by the sesshiga style derived from Chinese floral paintings of the Southern Song period. In this style, the artists created close-ups of a single branch or cluster of flowers, rather than depicting the entire plant. At the same time, however, the unusualness of his choices of subjects—here, a realistic carp streamer and turtle—reflect the unique sensibilities of this artist.

Hiroshige’s bold images offer strength and hope in dark times

It was with very special sentiments that Hiroshige crafted One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, a homage to his beloved hometown that was the culmination of a lifetime of artistry. The impetus for this grand work was Hiroshige’s reaction to a cataclysmic earthquake that struck Edo in 1855. The magnitude 7 tremors wrought destruction across the city, triggering huge infernos and taking more than 7,000 lives.

Hiroshige, who had served as a fire warden in his younger years, was shocked and saddened to see the flames devastate the city he had lovingly captured in his art for decades. In the following year, he became a Buddhist monk at the age of 60 and decided to pour all the artistic genius he cultivated over the years into producing One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, boldly highlighting in the foreground of these images, diverse symbols of a city rising from the ashes.

『名所江戸百景 水道橋駿河台』 (One Hundred Famous Views of Edo: “Suido Bridge and the Surugadai Quarter”)

Large-sized polychrome print, 1857, Nara Prefectural Museum of Art.

Large-sized polychrome print, 1857, Nara Prefectural Museum of Art.

This is a scene of streamers hung in celebration of the Tango-no-sekku holiday, looking toward Surugadai from Hongo heights. The banners and ribbon-like streamers in the background are flying over the homes of samurai; the lower classes, prohibited from erecting banners, decorated their homes with carp streamers instead. The large foreground image of a carp streamer sailing high in the sky, seemingly above Mt. Fuji, is believed to symbolize the revival of Edo following the 1855 earthquake.

The series entered publication just four months after the project was set in motion. Hiroshige ultimately crafted 119 woodblock scenes before passing away at 62, leaving behind a fantastic array of art filled with his heartfelt wish to contribute to Edo’s recovery and share with many, the joy of its rebirth.