Throughout history, art has served as a means for connecting to and expressing spirituality; art provides a natural vehicle for exploring the transcendental while the process of creating art can act as a form of philosophical meditation. Across cultures around the world, religious passion and contemplation on the meaning of life have given rise to an array of awe-inspiring artworks, including the depiction of paradise. How does one draw paradise? What does paradise look like for you?

The roots of the word “paradise” in many cultures referred to walled enclosures such as gardens or royal parks, and often today, people imagine paradise as idyllic scenes of Nature. Below, we compare the devotional Zen Buddhist works of a Japanese artist, 伊藤若冲 (Ito Jakuchu, 1716-1800) and the mystic symbolism in the paintings of French Post-Impressionist, Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin (1848-1903). Let’s see how Jakuchu and Gauguin convey their spiritual beliefs through depictions of Nature as paradise.

Jakuchu’s works convey the sacredness of all living beings

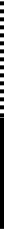

Ito Jakuchu, 「動植綵絵 老松孔雀図」 (“Colorful Realm of Living Beings, Old Pine Tree and Peacock”), hanging scroll, color on silk, 142.9 × 79.6 cm, circa 1757-1760, Museum of the Imperial Collections

Ito Jakuchu, 「動植綵絵 老松孔雀図」 (“Colorful Realm of Living Beings, Old Pine Tree and Peacock”), hanging scroll, color on silk, 142.9 × 79.6 cm, circa 1757-1760, Museum of the Imperial Collections

Though well loved for various reasons, the 18th century Kyoto painter, Ito Jakuchu, enjoys popularity for his vivid depictions of animals, such as the elegant white peacock seen above. Born as the son of a grocer, Jakuchu continued his father’s business. It is said that painting offered him creative respite from the monotony of daily life, and many examples of sketches made from careful observation of animals, such as his family’s chickens, remain. Eventually, Jakuchu passed the grocery business on to his brother, and afterwards took up painting full time while living the life of a 文人 (bunjin, literary intellectual) with strong ties to Zen Buddhism.

While Jakuchu’s almost hyperrealistic attention to detail and ability to capture the essence of the natural world demonstrate his artistic love for Nature, these aspects also point to his belief in the Buddhist concept concerning the divinity of life in all its various forms. This idea called 仏性 (bussho), claims that all living things have a Buddha nature, and it expresses the miraculous unity of Nature. A similarly wondrous treatment of the natural world and its creatures can be seen in many of Jakuchu’s works.

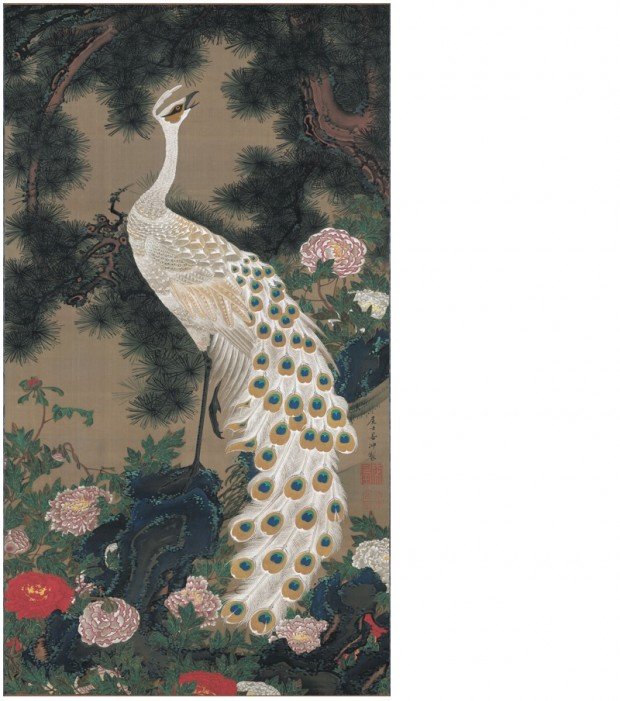

Ito Jakuchu, 「鳥獣花木図屏風」 (“Birds, Animals, and Flowering Plants in Imaginary Scene”), lefthand screen of pair of six-paneled screens, color on paper, 168.7 × 374.4 cm, Edo period (18th century), Etsuko & Joe Price Collection

Ito Jakuchu, 「鳥獣花木図屏風」 (“Birds, Animals, and Flowering Plants in Imaginary Scene”), lefthand screen of pair of six-paneled screens, color on paper, 168.7 × 374.4 cm, Edo period (18th century), Etsuko & Joe Price Collection

In the above screen, Jakuchu portrays an array of animals and birds great and small in a verdant, water-filled landscape. The mosaic-like background is comprised of diligently painted squares measuring 1 cm each. Reflecting the concept that all creatures can attain Buddha-hood, this work features wild beasts and birds who have attained Buddha-hood and now dwell harmoniously in paradise.

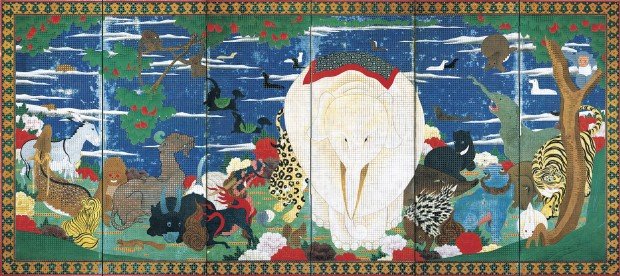

Ito Jakuchu, 「動植綵絵 群魚図(鯛)」 (“Colorful Realm of Living Beings, Fish, Red Snapper”), hanging scroll, color on silk, 142.3 × 78.9 cm, circa 1765-1766, Museum of the Imperial Collections

Ito Jakuchu, 「動植綵絵 群魚図(鯛)」 (“Colorful Realm of Living Beings, Fish, Red Snapper”), hanging scroll, color on silk, 142.3 × 78.9 cm, circa 1765-1766, Museum of the Imperial Collections

Perhaps Jakuchu’s most ambitious project and representative works is the series, 「動植綵絵」 (Doshoku sai-e, Colorful Realm of Living Beings), a set of 30-hanging scrolls featuring 花鳥絵 (kacho-e, bird-and-flower paintings) completed between 1757-1766. Detailed scenes of birds, fish, insects, mythical beasts, and plants fill the large-scale scrolls as a testament to the harmonious unity and sacredness of all living things. While the menagerie of creatures in 27 of the scrolls appear teeming with life, the seated figures of 3 bodhisattvas in the remaining 3 scrolls appear static in contrast. The difference can be said to provide a divine focus to Nature and wonder over its chaotic yet unified quality.

These silk scrolls were donated to Shokokuji Temple by the artist and are regarded as cultural treasures today. The Colorful Realm of Living Beings series conveys Jakuchu’s spiritual awe, and seems to attest to the idea that paradise can be found in Nature.

Gauguin’s paradise finds spiritual fulfillment by connecting with Nature

Similar to Jakuchu, Paul Gauguin also felt dissatisfied with working as a stockbroker and then Parisian businessman. He painted in his free time before trying to make a living as an artist. However, disillusioned with the European art scene, Gauguin escaped his notion of “civilization” to what he considered a more primitive yet spiritually fulfilling way of life by living with Nature in the French Polynesian islands, including Tahiti and the Marquesas.

Paul Gauguin, “Arearea,” 1892, oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, ©album/PPS

Paul Gauguin, “Arearea,” 1892, oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, ©album/PPS

In his painting “Arearea” from 1892, Gauguin found inspiration in both the colorful scenes around him in Tahiti as well as in the ancient stories and customs of the native peoples. In the background, we see that the artist has painted some sort of religious rite—believed to have been a creation of Gauguin’s imagination rather than from real life—to emphasize the direct relationship Gauguin believed humans should have with Nature. Meanwhile, the colorful, lush, and peaceful natural setting implies that this simple and very idealized archaic way of living in Nature is a form of paradise.

Gauguin’s works are noted for their experimentation with non-representational color and scenes of exoticism. His art style attempts to capture the inherent meaning of subjects rather than depict them with realistic accuracy. Gauguin’s island works carry spiritual overtones as they seek to harmonize man and Nature, or perhaps to put man back in his natural state, as well as to blend the mythical and supernatural with the everyday. In the artist’s mind, the tropical paradise-like, abstracted image of Nature held not only the key to his artistic quest, but also offered a more truthful answer to the meaning to human existence.