Interested in getting a Japanese omamori?

If you have ever visited a Japanese お寺 (otera, temple) or 神社 (jinja, Shinto shrine) and seen the many little brocade pouches, charms, and figurines available for purchase, perhaps all of the options seemed overwhelming. What does each お守り (omamori, amulet or charm) mean? How are they used?

Whether an avid collector of omamori or newly acquainted with these Japanese charms, read on to discover some interesting tidbits about omamori culture in Japan and how to find the right one(s) for your needs. Your concerns and questions are answered with our handy guide!

Various omamori including marriage, good fortune, and “Au-un” tiger omamori from Kuramadera Temple photographed by Shinohara Hiroaki, money pouches from Udo Shrine and a prosperity amulet from Togakushi Shrine photographed by Miyahara Muga.

Various omamori including marriage, good fortune, and “Au-un” tiger omamori from Kuramadera Temple photographed by Shinohara Hiroaki, money pouches from Udo Shrine and a prosperity amulet from Togakushi Shrine photographed by Miyahara Muga.

Why are so many things labeled as omamori?

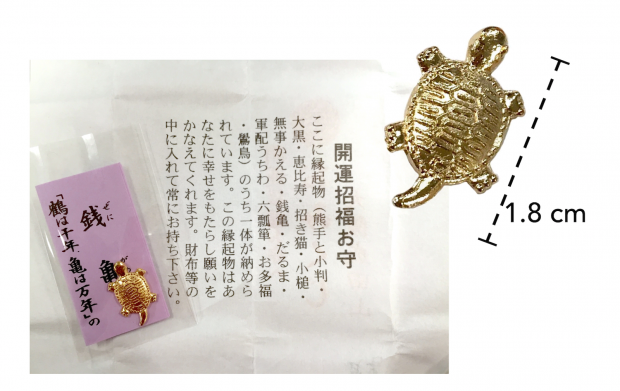

Looking around at the omamori selections at temples and shrines, you may be surprised to find that they come in many shapes and sizes, including charms fashioned into the forms of items considered auspicious in Japanese culture. For example, 瓢箪 (hyōtan, gourds) have been a common symbol used for good health since ancient times and turtles for longevity or wealth, while circles and knots symbolize eternal bonds. This 銭亀 (zenigame, pond turtle) charm featured easily fits into one’s wallet or bag, and is said to help ward off illness and procure wealth.

A written omamori with small gold turtle charm from Naritasan Temple in Osaka.

A written omamori with small gold turtle charm from Naritasan Temple in Osaka.

Zodiac animals like the horse pictured below, too are popular icons. Each shrine and temple often have their own special iconography, or mascot if you will, connected to their origin story.

Another type of omamori comes in the form of written sutras and power words tucked into colorful brocade packets and pouches like these monkey charms. The latter of these should never be opened or else the spiritual power will be released according to those who believe in its efficacy.

Year of the Horse ceramic bell from a shrine in Yamanashi next to good fortune monkey pouches from Hie Shrine photographed by Kitchen Minoru.

Year of the Horse ceramic bell from a shrine in Yamanashi next to good fortune monkey pouches from Hie Shrine photographed by Kitchen Minoru.

Which one should I buy?

Each omamori was designed with its own purpose and function. When giving omamori as a gift, it is better to keep the purpose in mind rather than choosing the most colorful or fancy-looking one if possible. The large selection of omamori available in Japan address a variety of concerns.

A small omamori charm from Imado Shrine in Tokyo.

A small omamori charm from Imado Shrine in Tokyo.

Each place often has its own unique omamori as well! For example, Imado Shrine in Asakusa, Tokyo is famous for the 招き猫 (maneki neko, beckoning cat) and matchmaking. One of its omamori pictured below combines both of these ideas with a cat tied with a 縁結び (enmusubi, marriage) ribbon.

What is the meaning behind each omamori?

While larger temples and shrines will probably have English explanations, smaller ones may not. Here is a basic guide to some of the more standard types of omamori you may encounter. Please note that the kanji characters may vary slightly.

・Happiness, 幸せ (pronounced shiawase)

・Good luck, 開運 (read as kaiun)

・Success, (勝守 katsumori) to achieve a particular goal such as securing a job or passing a test

・Love and matchmaking, 縁結び (en-musubi); there are also many pair omamori for couples to bestow happiness in their current relationship

・Good Health, 健康 (kenkō)

・Recovering from an illness, 病気平癒 (byōki heiyu)

・Safe childbirth, 安産 (anzan)

・Academic success, 学業成就 (gakugyō jōju) to pass examinations and aid in studying

・Prosperity and good business, 商売繁盛 (shōbai hanjō)

・Traffic safety, 交通安全 (kōtsū anzen)

・Warding off evil, 厄除け (yakuyoke), helps prevent misfortune from getting in the way of accomplishing one’s goals

You may notice that among the rows of omamori for sale are even those aimed for pets, for beautiful hair as well as prevention of hair loss, fertility, nice legs, a harmonious household, and safe travels. Apparently, there’s even one offered by Kanda Myojin Shrine in Tokyo to keep your computer running smoothly and stay safe from malware. The perfect omamori for you is out there!

What are these other charms also available for purchase?

When looking around for omamori, you may come upon a few other terms at a temple or shrine shop. Several types of lucky and protective items exist in Japanese culture, such as engimono, ofuda, and ema. Let’s take a look at what the differences are between these types of lucky talismans and omamori.

Maneki neko photographed by Yasukuni and a “demon-breaking arrow” from Meiji Jingu Shrine.

Maneki neko photographed by Yasukuni and a “demon-breaking arrow” from Meiji Jingu Shrine.

Originally engimono were items meant to bring about a change in one’s fortunes and were sold around the New Year season. Engimono are more like general lucky charms, but nowadays are not always constrained to the New Year holidays. The above maneki neko (beckoning cat) from Imado Shrine and hamaya (demon-breaking arrow) from Meiji Jingu Shrine to protect a household belong in the category of engimono.

Omamori can be thought of as portable amulets, often with prayers or power words written on paper or wood and enclosed in a cloth covering. At times they come in the form of small ceramic or metal charms and figurines, too, without a divine presence but could still ward off evil.

An ofuda and many wooden ema.

An ofuda and many wooden ema.

An ofuda differs slightly from an omamori, but in many regards is rather similar. It is a Shinto object meant to be placed in the household, and consists of a prayer written on wood or paper, and then wrapped in paper. In general, ofuda protect a household and family from calamities. The ofuda pictured above from Matsushima Shrine in Tokyo bestows good dreams. Lastly, an ema is a wooden votive upon which people write their wishes. Examples are seen above hanging on racks around a tree at Imado Shrine in Tokyo.

There are many interesting omamori and other talismans to discover in Japan! Enjoy looking around and we hope this guide helps you find the right charm(s) for you!

Written by Jennifer Myers