It is not uncommon that people of different cultures to you, may be taken aback at things that you may find completely ordinary.

History has repeatedly shown that such surprises have led to the creation of new cultures.

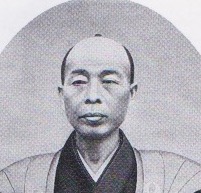

Hasekura Rokuemon Tsunenaga (支倉六右衛門常長), a samurai of the Sendai domain, served under Date Masamune, and in 1613, he led the ‘Keicho ken-o shisetsu dan (慶長遣欧使節団/European mission)’ to Europe on Masamune’s order.

The presence of Japanese was so rare in Europe at that time that there was even a parade in Rome. There is an episode that symbolises such rarity of Japanese. It is as follows,

“A piece of paper Hasekura blew into and threw away when they sneezed was later exhibited in a museum in Rome.”

…… That’s disgusting. Why did they keep something like that? Would it be more valuable to collect things like swords, and armour?

Searching through literature to find the answers to these questions, eventually led me to the ‘Bibloteca Angelica’ in Rome.

First, let’s review the ‘Keicho ken-o shisetsu’, commonly known from Japanese school textbooks

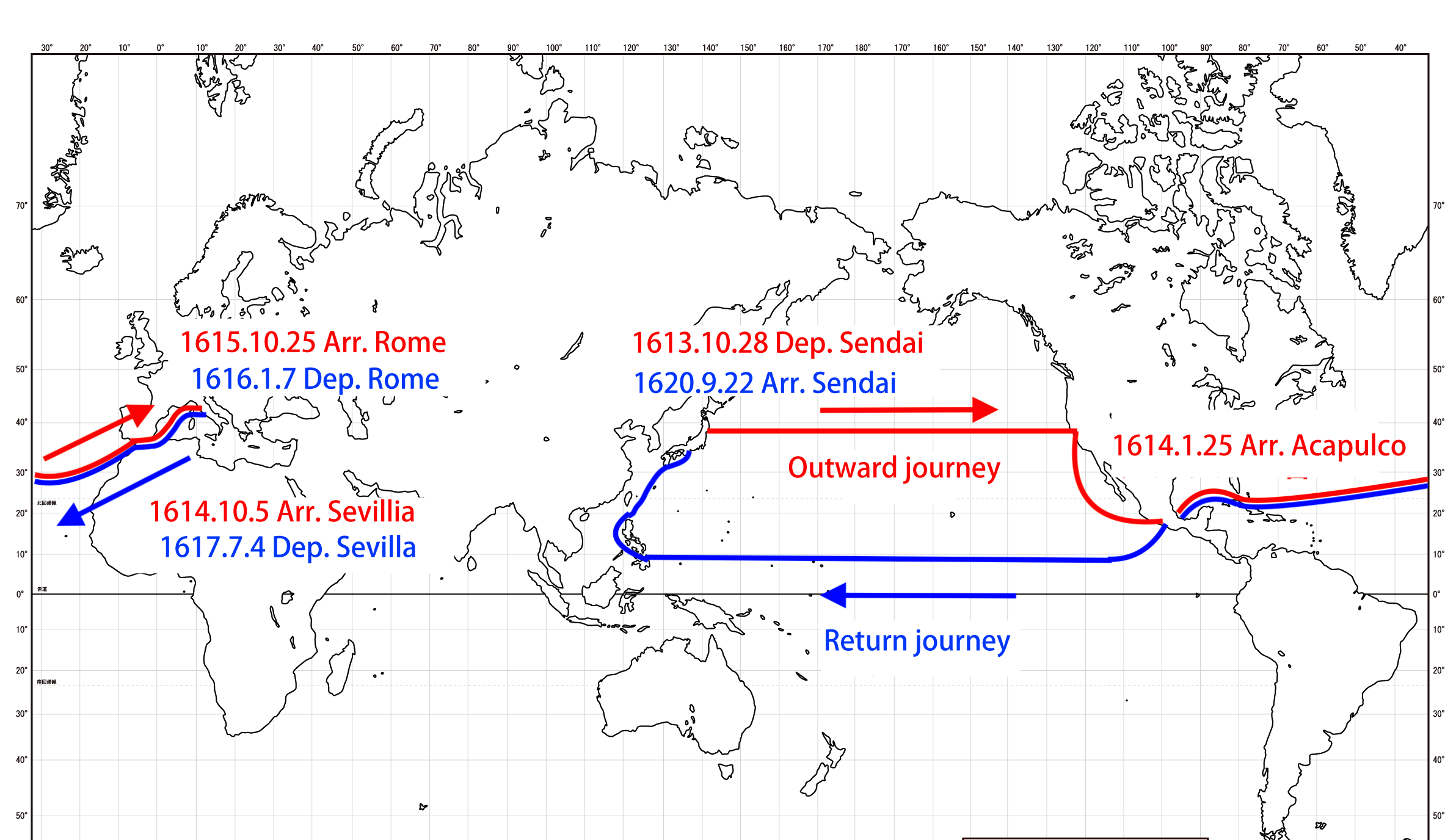

On October 28, 1613 (September 15, Keicho 18), Date Masamune (伊達政宗), lord of the Sendai domain, dispatched his retainer, Hasekura Tsunenaga, to Spain and Rome via present-day Mexico.

The purpose of the mission was to negotiate direct trade with Mexico. More than 180 people, including Spanish interpreters, boarded a sailing ship and sailed across the Pacific Ocean to South America, then across the Atlantic Ocean to Europe.

This group is called the ‘Keicho ken-o shisetsu dan’, and along with the ‘Tensho ken-o shisetsu (天正遣欧使節)’, which had departed about 30 years earlier, it is an epoch-making achievement in Japanese history, and is always mentioned in textbooks.

Hasekura stayed in Rome for a while, even obtaining citizenship, and returned to Japan in 1620, seven years after setting sail. The portrait of Pope Paul V and Christian ritual implements he brought back with him at that time were designated as national treasures in 2001 as valuable materials that “tell the reality of the negotiations between Japan and Europe in the early Edo period”.

2520 Nights 2521 Days Trip

In modern times, it would take only one day to reach Rome by plane, even if you were traveling around the Pacific Ocean, but it took Hasekura and his group two years to reach Rome.

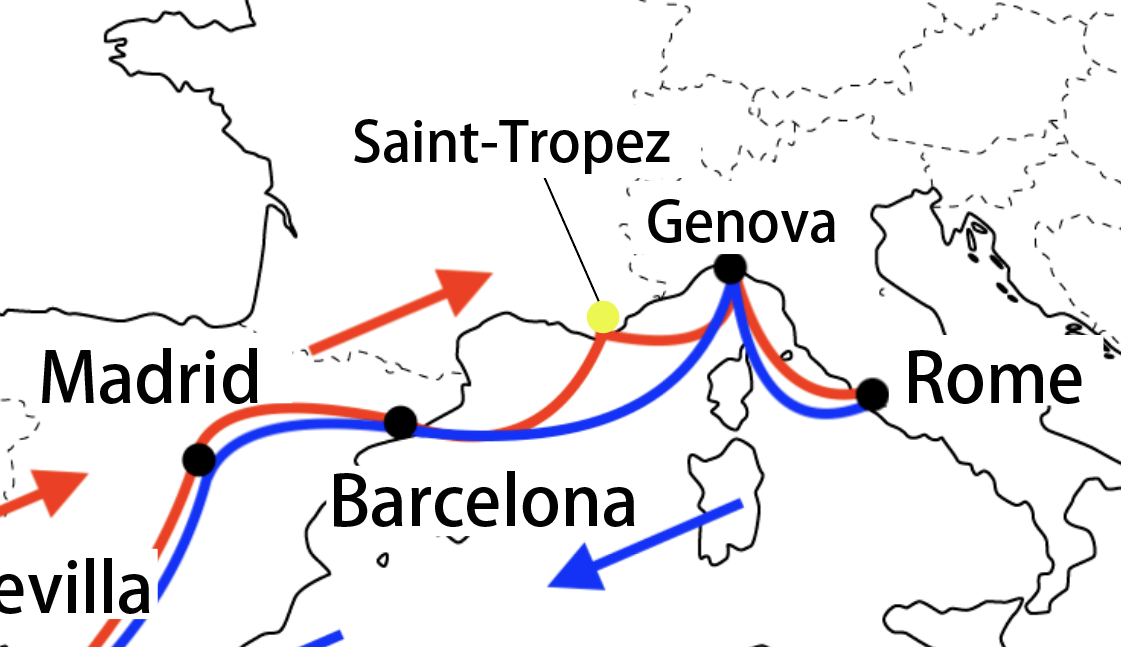

They departed in October 1613. From there, they crossed the Pacific Ocean to Acapulco in South America, which took three months. After staying in Mexico, he left there on March 24, 1614, and traveled to Seville, Spain, for six months.

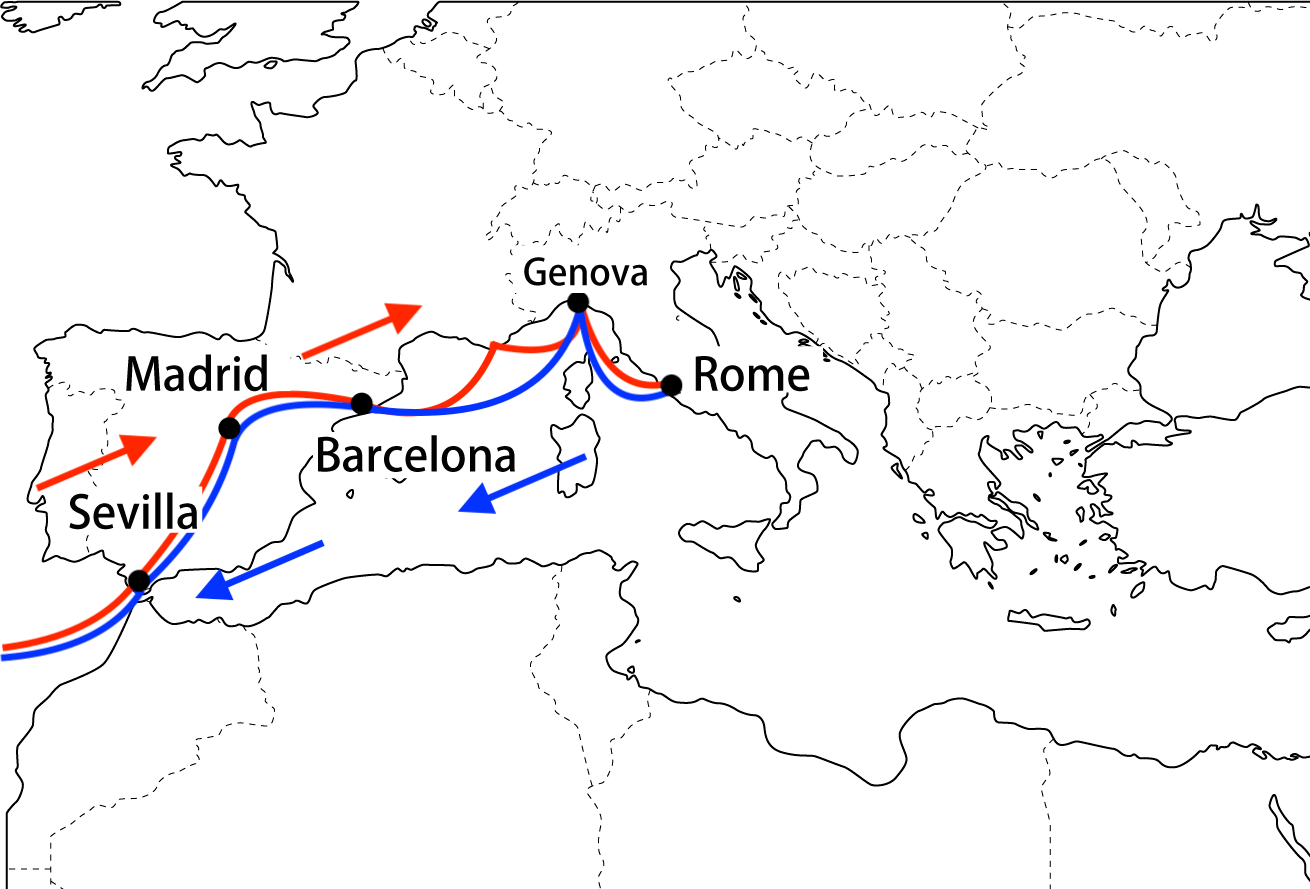

From there, he travelled overland across Spain and from Barcelona to Italy by sea.

From there, he travelled overland across Spain and from Barcelona to Italy by sea.

He arrived in Rome in October 1615, one year after his departure from Spain and two full years after his departure from Sendai.

For a long time, it was actually believed that “Hasekura and his party sailed from Barcelona and then went directly to Italy”.

However, at the beginning of the 20th century, an unexpected document was found in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris. They were memoirs and letters of the Marquis of Saint-Tropez, who ruled the small French port town of Saint-Tropez, and his wife.

The shisetu dan from Barcelona was caught in a storm in the Mediterranean Sea and made a hasty port stop here, which was the first time a Japanese person stepped on French soil. (Until the discovery of this memoir, the first Japanese person to visit France was thought to be Takenouchi Yasunori (竹内保徳), the head of the Edo Shogunate’s ken-o shisetsu dan tyo (遣欧使節団長) in 1862. It was a significant discovery in the history of French-Japanese exchange that set the record straight for more than 250 years.)

Fighting over a paper handkerchief

The “Hanagami jiken (鼻紙事件: paper handkerchief Incident)” (named on its own) occurred in this Saint-Tropez.

Let’s take a look at the journal of the Marquise of the time, translated by the historian Ishida Mikinosuke (石田幹之助).

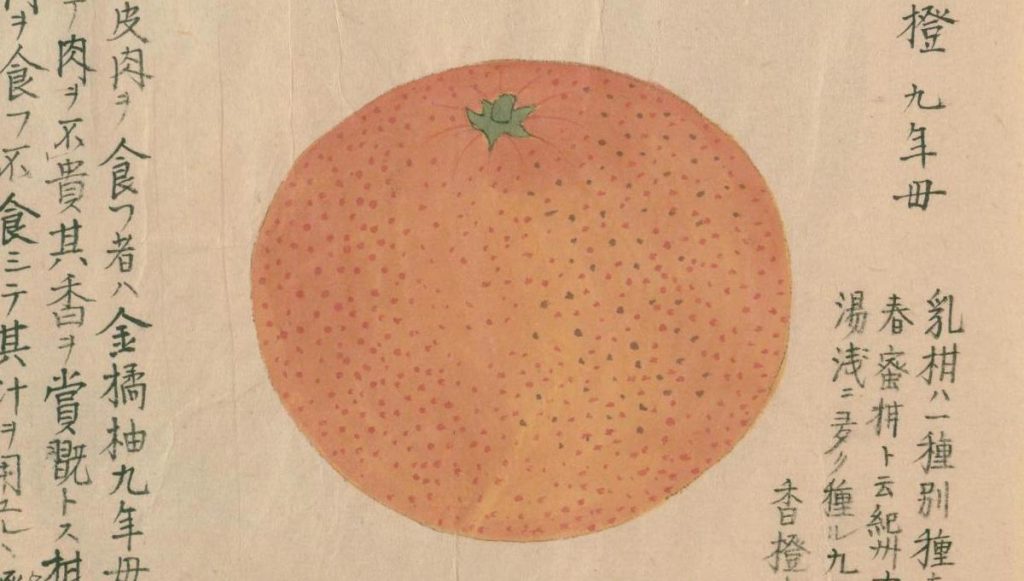

‘They used a large piece of paper as a handkerchief, and blew their nose into it, and discarded it after every use, never using the same piece more than once.

The Japanese kept these handkerchiefs in their clothes as if they were the most luxurious love letters of a courtesan. They carried a considerable amount in their pockets, but they had enough for the long journey ahead.

The people of St. Tropez were said to be eagerly awaiting the Japanese to go out. and this was indeed true.. Whenever one of the Japanese used a handkerchief and threw it away, they would rush over and pick it up. People fought each other to get their hands on this precious souvenir.

The most valuable of all was Hasekura’s handkerchief. Hasekura’s handkerchief had historical value in the eyes of the people.’

(Ishida Mikinosuke, ‘Date Masamune no osyukenshi ni kansuru sinjijitsu ni tuite (On the New Facts Concerning Date Masamune’s Envoy to Europe)’, in The Works of Mikinosuke Ishida, Vol. 3 (1986, Rokko Shuppan). (Lines have been broken as appropriate for ease of reading.)

The Marquise saw that the group was blowing their noses with a ’silk handkerchief’, but it is assumed a Kaishi (懐紙: paper folded and tucked inside the front of one’s kimono esp. for use at the tea ceremony or writing a Tanka).

Because we can see other descriptions to this “silk”,

(They are) writting characters from the top down with a brush on the silk”

and that each had a considerable amount of it in their pocket, we can conclude the silk is Kaishi paper.

In Japan, it was common to use paper for blowing one’s nose, such as Asakusa paper ( made from recycled paper that has been reworked) made in the Asakusa, Tokyo and Ueda paper from Nagano, as in the Edo period senryu (川柳), “Hana wo kamu Kami ha Ueda ka Asakusaka (Is the paper for blowing one’s nose Ueda or Asakusa?)” (Reference: ‘Washi no ohanashi (和紙のおはなし)’ by Tokyo Washi Co.)

On the other hand, in Europe at that time, it was common to use a handkerchief or hands to blow one’s nose. The use of paper must have been very rare.

The result of the meeting of such two cultures,

Hasekura “Achoo!

↓↓↓↓

Blow his nose and throw away the paper

↓↓↓↓

French people “Wow! Give me some too!”

↓↓↓↓

Fistfight over the paper handkerchiefs

It was a very strange scene.

Almost comparable to children flocking to grab leaflets scattered by street advertisers.

Moreover, it seems that the Hasekura group also got carried away, blowing their noses and throwing away more and more.

I had no idea that this was the first encounter between a Japanese and a Frenchman. The history of the two countries began with a very bizzare scene. In addition to this, the Marquise also describes in detail Hasekura’s appearance, the group’s clothing, and the swords they each carried.

Asked the library in Rome

The numerous paper handkerchiefs blown into by Hasekura’s group later became perhaps ‘the most valued paper handkerchiefs in human history’.

It was even transported to Rome, where it was displayed in a museum.

According to Yamauchi Hisashi (山内昶), in his book ‘Shoku no rekishi jinruigaku’ (「食」の歴史人類学) (1994, Jinbunshoin),

“Several pieces of what is believed to be Hasekura’s scraps of paper are still kept in the Angelica Museum (Library) and the Anthropological Museum in Rome.”

…… Seriously? So I contacted the Angelica Library.

Me “Sorry to bother you. I heard about ……, is it true?”

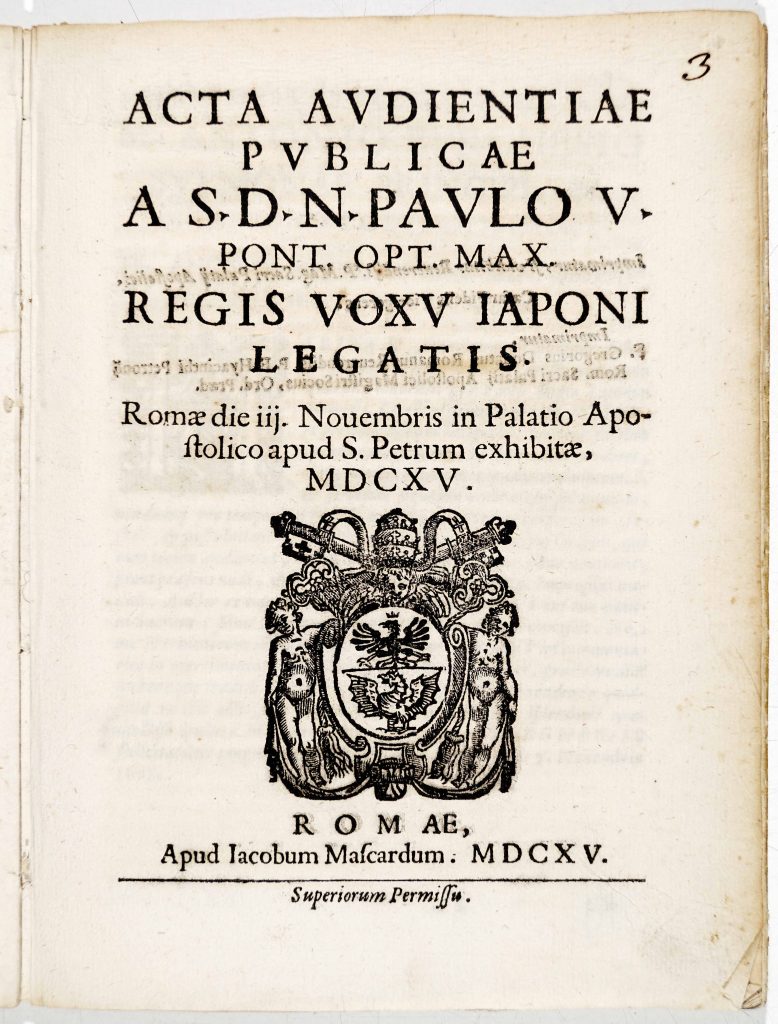

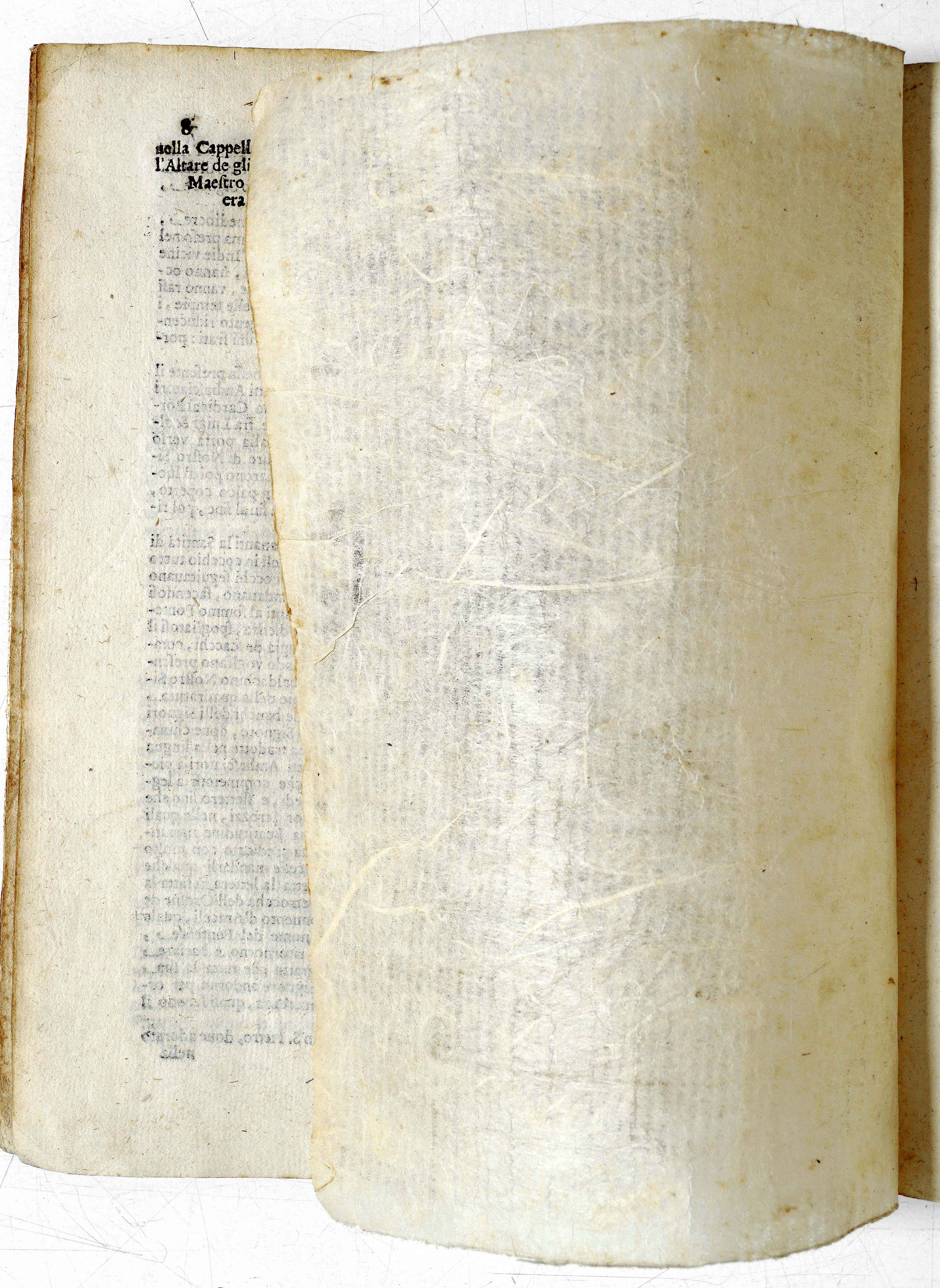

Ms. Anna Letizia Di Carlo (Rare Book Room, Biblioteca Angelica). “Yes, it is true! The paper is kept with the miscellaneous documents written in 1615. Here are those documents.”

……It was really there(I had thought it probably wouldn’t be).

Anna: “In this book, you will find the paper handkerchief you are looking for”.

Indeed, the paper quality is different from the other pages, indicating that only this section is Japanese paper.

So it was a kaishi, after all.

Unfortunately, we couldn’t see any trace of snot (we also can’t believe we were looking for it), but the paper handkerchief that Hasekura blew on was indeed kept in Rome.

Anna said, “We also have a portrait of him in our museum.

And here it is.

There are actually many mysteries about the portrait of Hasekura Tsunenaga. If you are interested, please refer to ‘Hasekura Tsunenaga Keicho ken-o shisetsu no shinso : Syozoga ni himerareta jitsuzo (支倉常長 慶長遣欧使節の真相:肖像画に秘められた実像)’ by Oizumi Koichi (大泉光一), who has researched the portrait in detail.

The clothes and hairstyle were probably extremely unusual for them at the time. The way the sleeves are strangely plump and the way the side arms are stuck in the right hip, one can imagine that the artist probably thought, “What the heck is he wearing?

Unfortunately, we did not know how this library got their hands on this paper handkerchief, whether it was collected by Bishop Angelo Rocca, or whether it has ever been exhibited in addition to being stored.

However, the artefact is definitely from 1615, and Anna sent me this other page of relevant descriptions.

(but I’m not going to go into that here as it would take me forever to translate it, but I’ll look into it in the future)

This is indeed Rome, where all roads lead. The quality of their library collection is also astounding.

When you encounter “common sense” that is different from yours

Encounters with other cultures are sometimes met with shock. Because of the magnitude of that shock, humankind has repeatedly looked down on, rejected, or even discarded such cultures.

We must not forget the fact that Europe was still in a period of war at the time of Hasekura’s arrival in Europe and for a long time afterward, but from this paper handkerchief, which has been carefully preserved for more than 400 years, and the many records written down in detail, is it just me who feels that the people of that time did not merely admire Hasekura and his party and Japanese customs as a spectacle, but studied them and tried to learn something from them.

How do we behave when we come into contact with ‘common sense’ or ‘the norm’ that is different from our own?

I feel that we in modern Japan have much to learn from this ‘most valued paper handkerchief in the history of humankind’.

(Incidentally, it was not until 1872, 250 years after Hasekura’s arrival in Europe, that the Kimberly-Clark Company of Wisconsin, USA, developed and sold tissues, so it does not appear that the custom of paper sniffing spread in Europe.)

References other than those listed in the text

Ota Naoki, Hasekura Tsunenaga ken-o shisetsu mouhitotsu no isan – sono tabiji to nihon-sei supein-jin tati (『支倉常長遣欧使節 もうひとつの遺産−−その旅路と日本姓スペイン人たち』) (Yamakawa Shuppansha, 2013).

Oizumi Koichi, Hasekura Rokuemon Tsunenaga ‘Keicho ken-o shisetsu’ Research kenkyu shiryo syusei (『支倉六右衛門常長「慶長遣欧使節」研究史料集成』) (Yuzankaku, 2010)

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/rock/culture-rock/140907/