Dr. Makino Tomitaro (牧野富太郎), who laid the foundations of Japanese plant taxonomy, made headlines when he was used as the model for the TV morning drama ‘Ranman (らんまん)’ in the first half of 2023. Dr Makino collected some 400,000 plant specimens in his lifetime. The number of botanical drawings he made amounted to approximately 1,700.

What was his 94-year life like as a lover and researcher of plants? Here is a digest of his life and works.

The botany born from the man who called himself the ‘spirit of plants’

Makino Tomitaro

Makino Tomitaro

Makino Tomitaro was born at the end of the Edo period in 1862 as the eldest son of a wealthy merchant family running a sake brewery in Sakawa (佐川) village (now Sakawa town), Takaoka (高岡) county, Kochi prefecture. Although he lived a comfortable life, his parents and grandfather died one after the other before he could remember anything, and he was brought up by his grandmother. He was a child who liked to play alone with plants and trees. In early spring, the area around Kinpu Shrine (金峰神社) on the hill behind the shrine was covered with the flowers of the baikaoren, which was probably Dr Makino’s indelible scene, with the baikaoren being his favourite flower.

Baikaoren

Baikaoren

Sakawa Village is an area where learning flourished, and the local school, Meikyokan (名教館), was built by the Fukao (深尾) clan, the feudal lord of the village. Tomitaro also studied at a terakoya (寺子屋) and a private school before entering Meikyokan, where he studied various cutting-edge Western subjects. In 1874, when the school system was introduced, the school building of Meikyokan became a primary school, which Tomitaro also started attending, but he felt unsatisfied with the classes and dropped out after two years. After leaving primary school, Tomitaro went to Yokokurayama (横倉山) in Ochi cho (越知町) and the surrounding mountains to collect plants and learnt botany on his own. The rich mountains and fields of Tosa (土佐) nurtured Tomitaro, and learning from actual experience became the starting point of his studies.

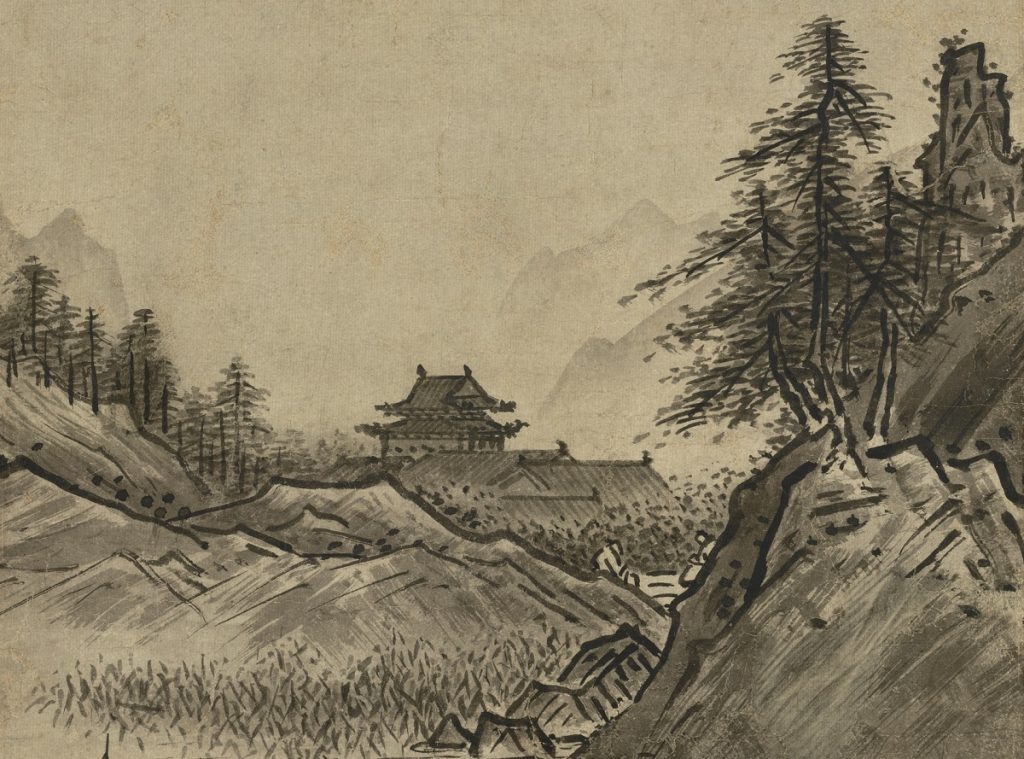

The approach from the main gate of the Makino Botanical Garden to the main building is an ecological garden of plants growing in the diverse natural environment of Kochi Prefecture.

The approach from the main gate of the Makino Botanical Garden to the main building is an ecological garden of plants growing in the diverse natural environment of Kochi Prefecture.

He eventually decided to pursue botany and moved to Tokyo in 1884 at the age of 22. He immersed himself in full-scale botanical research while working in and out of the Botany Department of the Faculty of Science at the University of Tokyo. In 1887, he and a friend founded the Botanical Journal, which was prefaced by an article by Tomitaro. In 1889, he was the first in Japan to give a scientific name to a new species, Yamatogusa (ヤマトグサ), discovered in Tosa, and published it in the Botanical Journal. This was a memorable moment when the Japanese were able to give it a scientific name on their own, without relying on foreign scientists. He left a significant mark on the pioneering period of Japanese botany.

Soukei nozeng (Nouvellaceae), Kent paper, Ink (brush), watercolour / Meiji 14 (1881), 13.7 x 19.3 cm

Soukei nozeng (Nouvellaceae), Kent paper, Ink (brush), watercolour / Meiji 14 (1881), 13.7 x 19.3 cm

Dr Makino traversed the entire country, discovering and naming some 2,500 plant species. This number represents about half of Japan’s higher plant species above the fern level. He travelled around Japan, guiding plant enthusiasts and popularising botany to the masses.

In botany, botanical illustrations are indispensable as a record of research, as they enable the characteristics of plants to be expressed and recorded more clearly than text. In this respect, Dr Makino had keen powers of observation and a natural talent for skilful and precise drawing, and he accurately and faithfully sketched the plants he discovered.

Botanical specimens of Himehydrangea (Saxifragaceae) collected in Oizumi (大泉), Nerima-ku (練馬区), Tokyo, where Dr Makino’s home was located.

Botanical specimens of Himehydrangea (Saxifragaceae) collected in Oizumi (大泉), Nerima-ku (練馬区), Tokyo, where Dr Makino’s home was located.

First, we focus on the typical forms of plants, examining the most representative forms from the many collected, and then sketching them in detail under close observation using loupes and microscopes. The forms of the species, which are necessary for botanical taxonomy, are then drawn in full. Flowers and seeds are also drawn throughout the year, and these partial drawings are reconstructed on a single sheet of paper to include as much information as possible on the characteristics of the plants.

Oleander (Oleaceae), Kent paper, Ink (brush), watercolour / Meiji 14-15 (1881-’82), 13.6 x 19.5 cm

Oleander (Oleaceae), Kent paper, Ink (brush), watercolour / Meiji 14-15 (1881-’82), 13.6 x 19.5 cm

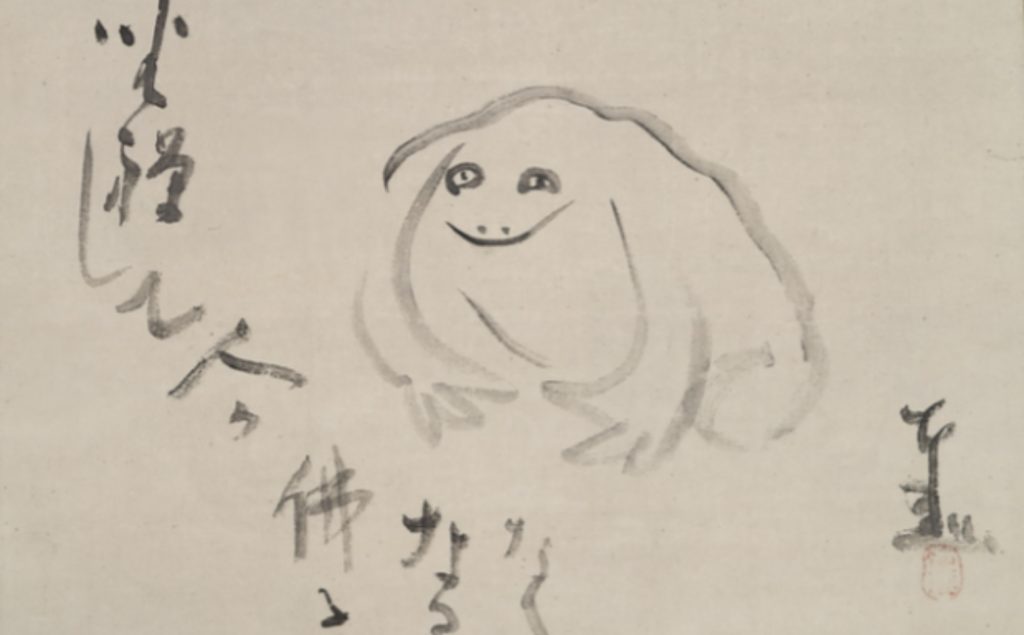

Most of the botanical drawings are drawn with maki-e (蒔絵) or mensou (面相) brushes with extremely fine tips, known as three rat’s hairs. If you look closely, you can see extremely fine lines within a single line, or fine hairs on the surface, a truly microscopic depiction. Although drawn with a brush, they are as sharp as copperplate engravings and also capture the texture of the plants.

At the time, there were no paints available in Japan that could produce actual colours, so he used the finest Winsor Newton paints made in England. During his lifetime, he refined his drawing techniques by sketching approximately 1,700 works and established an advanced botanical drawing method known as the ‘Makino method’. His spirit to capture plants in minute detail in his drawings and his thorough research attitude in patiently working with plants are evident. He called himself a ‘somoku no sei (草木の精, the spirit of plants and trees)’, and it can be said that his work could only have been created through the eyes of a man with an unbounded love for plants.

Jorohototogis (Liliaceae), lithograph print, watercolour / 1888 (Meiji 21) ‘Nihon shokubutsu shi zuhen (日本植物志図篇)’, vol. 1, no. 1, fig. 1.

Jorohototogis (Liliaceae), lithograph print, watercolour / 1888 (Meiji 21) ‘Nihon shokubutsu shi zuhen (日本植物志図篇)’, vol. 1, no. 1, fig. 1.

He had a great ambition to produce a superior botanical journal with precise botanical drawings and descriptions that would rival Western publications, and in 1888 he self-published ‘Nihon shokubutsu shi zuhen (日本植物志図篇, Japan Botanical Atlas)’ . He was so particular about this that he not only produced the original drawings, but also did the lithographic printing himself, accurately and faithfully recording the flora. By this time, his family had fallen on hard times and he had 13 children, but in 1900 he produced the ‘Dai Nihon Shokubutsu Shi (大日本植物志, The Botanical History of Japan)’. In this work, Dr Makino’s enthusiasm to demonstrate Japan’s academic standards to the world can be felt. Eventually, the sophisticated Makino method of botanical illustration was completed, and its precise diagrams were highly regarded overseas.

Kochi Prefectural Makino Botanical Garden

Official website

Botanical maps and photographs courtesy of the Kochi Prefectural Makino Botanical Garden

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/rock/travel-rock/1886/