When we think of ukiyo-e (浮世絵) hanga (版画; art prints), vibrant colours often come to mind. However, at the beginning of the Edo period, these prints were only produced in monochrome ink. Later, a technique called Benizurie (紅摺絵; red prints) *1 emerged, which incorporated colors like vermillion. Over time, the techniques advanced, and vibrant, multi-colored ukiyo-e hanga began to flood the market. These prints, which were as elegant as brocaded textiles (nishiki-ori; 錦織), came to be known as nishiki-e (錦絵). Suzuki Harunobu (鈴木春信), the ukiyo-e artist we introduce here, played a major role in this evolution of ukiyo-e hanga.

Quiz, Who painted Shunga? Even those famous painters!?

Interactions with cultural figures broadened his horizons as an artist

The details of Harunobu’s birth remain unclear, but he is believed to have been born around the Kyoho era (1716-1736). His family name was Hozumi (穂積), he was commonly known as Jirobei (次郎兵衛), and he adopted the art name Shikojin (思古人). Later in life, he became an artist and is said to have resided in the Shirakabe (白壁) district of Kanda (神田), Edo (near present-day Kanda Kajicho; 神田鍛冶町). This area was home to many affluent scholars and cultural figures. Among them, he is thought to have been especially close with Hiraga Gennai (平賀源内), a noted expert in herbal medicine, Western studies, and renowned for his work with electric devices. Harunobu also had connections with Ota Nanpo (太田南畝), who wrote satirical poetry and comic novels, Sugita Genpaku (杉田玄白), a Dutch-trained physician, and Odano Naotake (小田野直武), an Akita domain samurai and Western-style painter. It was fortunate for Harunobu to have received the support of such well-educated individuals.

*3. Sugita Genpaku, a physician who translated and published ‘Kaitai Shinsho (解体新書)’, a pioneering medical text.

*4. Odano Naotake was a Western-style painter from the late Edo period who studied with Hiraga Gennai.

He quickly rose to fame as an artist by creating ‘Egoyomi (絵暦; picture calendars),’ a popular trend at the time

Around 1760 in the Horeki period, Harunobu began creating actor portraits using benizurie. By the early Meiwa (明和) era, a popular pastime among samurai, the wealthy, and cultural figures involved exchanging ‘egoyomi (絵暦)’—illustrated prints with calendar information embedded within beautiful artwork, similar to modern calendars. Harunobu was commissioned by individuals such as Okubo Tadanobu (大久保忠鋸), a shogunate retainer and haiku poet, to produce egoyomi. As this trend gained popularity, publishers saw an opportunity to market these egoyomi to the general public, with Harunobu at the forefront of this production.

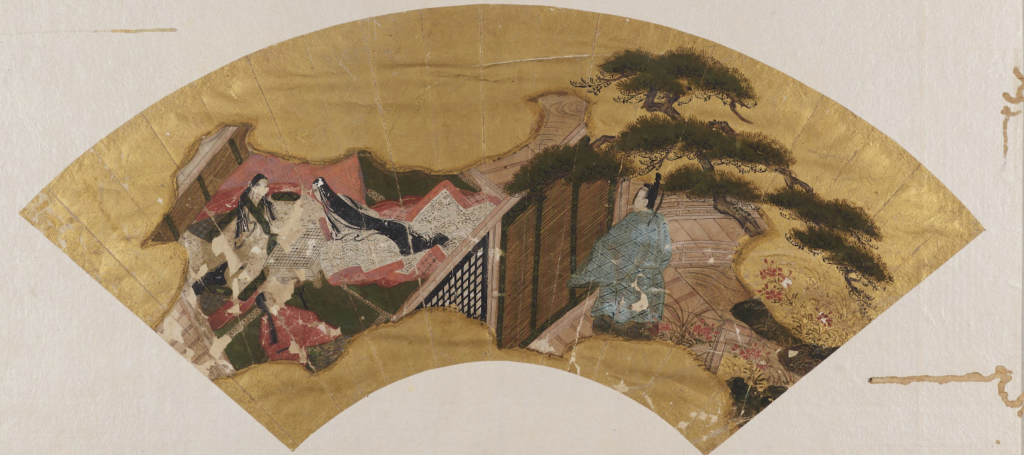

Depicting classical stories and waka poetry using the ‘mitate (見立)’ technique

Even today, the term ‘mitate (見立)’ refers to the practice of replacing one thing with another. Harunobu’s works feature numerous examples of this ‘mitate-e (見立絵; allusive art)’. He also employed a technique known as ‘Yatsushi (やつし)’, where classical and elegant subjects, such as the poets from the Thirty-Six Immortal Poets and stories from the ‘Ise Monogatari 伊勢物語)’, were depicted in contemporary settings. The incorporation of classical narratives into his artwork, along with his portrayal of androgynous figures, resonated with many samurai and cultural figures, allowing him to establish a distinctive worldview.

*7. The practice of representing something once considered authoritative or prestigious in a more accessible or familiar manner, reflecting contemporary styles.

Expressing beautiful women and lovers with rich sentimentality

Harunobu continued to capture the tender moments of lovers, such as in his famous masterpiece ‘Setchu aiai gasa (雪中相合傘)’, portraying their delicate expressions and intimacy. He gained widespread acclaim for his lyrical depictions of beautiful women. His artistic style is said to have been influenced by prominent Edo period ukiyo-e artists like Nishimura Shigenaga (西村重長), Okumura Masanobu (奥村政信), and Torii Kiyomitsu (鳥居清満), as well as by Nishikawa Sukenobu (西川祐信) from Kyoto.

In his shunga, he depicted a humorous world with extraordinary and imaginative concepts

Having likely learned the fundamentals of painting from them, Harunobu gradually shifted his focus to the everyday lives of common people, portraying the daily lives of those who worked in the Yoshiwara red-light district, as well as themes involving parents and siblings. In his later years, he produced numerous ukiyo-e prints, such as ‘Ehon Seiro Bijin Awase (絵本青楼美人合)’, which depicted courtesans by their real names. He also created images inspired by well-known figures of the time, including Kasamori Osen (笠森お仙), the popular young woman from the teahouse Kagiya (鍵屋), and Ofuji (お藤) from the toothpick shop Motoyanagiya (本柳屋).

In his shunga, he released what would become one of his representative works, ‘Furyu Enshoku Maneemon (風流艶色真似ゑもん)’. This print features a man named Maneemon, who shrinks after drinking an elixir, traveling across various regions and pleasure districts to indulge in sexual practices while peeking into the secret affairs of men and women. This extraordinary concept garnered much attention, showcasing Harunobu’s sense of humour, which resonates with contemporary audiences.

A dynamic innovator in ukiyo-e, he created a vast body of work that became a monumental cultural phenomenon

Harunobu, who depicted a vibrant world, was active as an artist for a brief period of just over ten years, from around Horeki (宝暦) 10 to Meiwa (明和) 7. During this time, he created approximately 1,000 ukiyo-e hanga and published 16 book editions. As a true pioneer of his era, Harunobu produced a vast body of work that established the nishiki-e as a significant cultural phenomenon before passing away in Meiwa 7.

References: Edo no ninki yukiyo eshi (江戸の人気幸代絵師) by Naito Masato (内藤正人), Gentosha Shinsho (幻冬舎新書); Sekai daihyakka jiten (世界大百科事典; Shogakukan (小学館) Digital); Nihon daihyakka jiten (日本大百科全書; Shogakukan)

Header image: ‘Anto no Yusho (あんとうの夕照)’ from the series ‘Zashiki Hakkei (坐鋪八景)’, from The Art Institute of Chicago

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/rock/culture-rock/240591/