Even today, collectible photo prints of favourite idols are treasured by fans. Similarly, during the Edo period, owning ukiyo-e prints of popular yujo (遊女) or kabuki (歌舞伎) actors was a common aspiration among townspeople. Among the artists who captivated the public with lifelike portraits of actors was Katsukawa Shunsho (勝川春章). Though his name may not be widely recognised today, he was the master of the renowned ukiyo-e artist Hokusai (北斎) and is said to have influenced Sharaku (写楽) ’s actor portraits.

Apprentice to ukiyo-e pioneer, Hishikawa Moronobu

Shunsho is believed to have been born during the Kyoho (享保) era, a time when the turbulent Sengoku (戦国) period had faded into history, and a peaceful, pleasure-seeking society thrived. As townspeople began to have disposable income for entertainment, kabuki theatre and the pleasure quarters became the height of fashion. Traditionally, painting was the domain of the aristocracy and samurai, who commissioned artists for wall and screen paintings. However, artists found inspiration in the customs and lifestyles of the common people, leading to the creation of genre paintings depicting yujo and actors. The Ukiyo-e Ruiko (浮世絵類考), compiled by Ota Nanpo (大田南畝) during the Kansei (寛政) era, notes:

Katsukawa Shunsho, a disciple of Katsukawa Shunsui (勝川春水), resided in Ningyocho (人形町). He was renowned for his kabuki actor portraits during the Meiwa (明和) period and was also known as Katsumiyagawa (勝宮川).

While his origins are not definitively known, Shunsho is thought to have been born around 1726 and lived in Tadokoro-cho (田所町), Nihonbashi (日本橋), Edo. Some sources suggest his real name was Fujiwara Masateru (藤原正輝), commonly known as Yosuke (要助). Besides the art name Shunsho, he used several pseudonyms, including Kyokurosei (旭朗井), Kirin (李林), Yuji (酉爾), and Rokurokuan (六々庵).

At that time, ukiyo-e were primarily monochrome prints or hand-painted works, making them expensive one-of-a-kind items. Artists like Hishikawa Moronobu (菱川師宣)*1, considered the founder of ukiyo-e, specialised in hand-painted bijin-ga (美人画, portraits of beautiful women), while Torii Kiyonobu (鳥居清信)*2 depicted kabuki actors. After Moronobu’s death, Miyagawa Choshun (宮川長春)*3, who followed in his stylistic footsteps, gained popularity for his bijin-ga. Choshun’s student, Miyagawa Shunsui, became the master of Katsukawa Shunsui (勝川春水)*4, who in turn taught Shunsho, making Shunsho a third-generation disciple of the Miyagawa school.

*2 An ukiyo-e artist of the mid-Edo period. He pioneered the hereditary tradition of producing kabuki signboards and theatre programmes, and is considered the founder of the Torii (鳥居) school, which continues to this day.

*3 A mid-Edo period ukiyo-e artist and the founder of the Miyagawa school. He specialised in hand-painted portraits of beautiful women (bijin-ga).

*4 A disciple of Miyagawa Choshun, known for his skill in hand-painted bijin-ga. Founder of the Katsukawa school, under whom Katsukawa Shunsho studied.

A tale resembling the tale of the 47 Ronin? The controversial origins of the Katsukawa School

In 1750, Choshun undertook part of the restoration work at Nikko Tosho-gu (日光東照宮) under the direction of Shunga (春賀), head of the Inaribashi (稲荷橋) branch of the Kano (狩野) school and an official painter for the shogunate. Despite the high praise for the completed work, payment was not forthcoming. Frustrated, Choshun visited Shunga’s residence to demand his due. However, given the low social status of ukiyo-e artists at the time, Shunga’s disciples deemed Choshun’s actions insolent. They assaulted the elderly artist, bound him with rope, and discarded him in a rubbish heap.

Choshun was rescued by his son and disciples, but their anger did not subside. They stormed the Kano residence and killed Shunga and his followers. This incident, reminiscent of the tale of the forty-seven ronin, led to the dissolution of the Inaribashi Kano family (稲荷橋狩野家) due to embezzlement of artists’ payments. Choshun’s son committed suicide, one of his senior disciples was exiled to Niijima in Izu (伊豆新島), and Choshun himself was temporarily banished from Edo. He died two years later from complications of his injuries.

In the wake of this scandal, Shunsui and his followers changed their artistic surname from Miyagawa to Katsumiyagawa and continued their work discreetly. Eventually, they adopted the name Katsukawa, founding the Katsukawa school. This rebranding coincided with the rising popularity of Shunsho’s realistic actor portraits, marking the tumultuous beginning of his illustrious career in ukiyo-e.

Revolutionizing the world of actor portraits

Though Shunsho spent many years in obscurity and became entangled in the unfortunate incident involving the Miyagawa school around the age of 23, the times seemed to favour him. Ukiyo-e, previously rendered solely in black ink, evolved rapidly into multi-block, multi-colour nishiki-e (錦絵) prints. The first to adopt this technique was Suzuki Harunobu (鈴木春信)*5, and Shunsho soon followed suit, mastering the new methods.

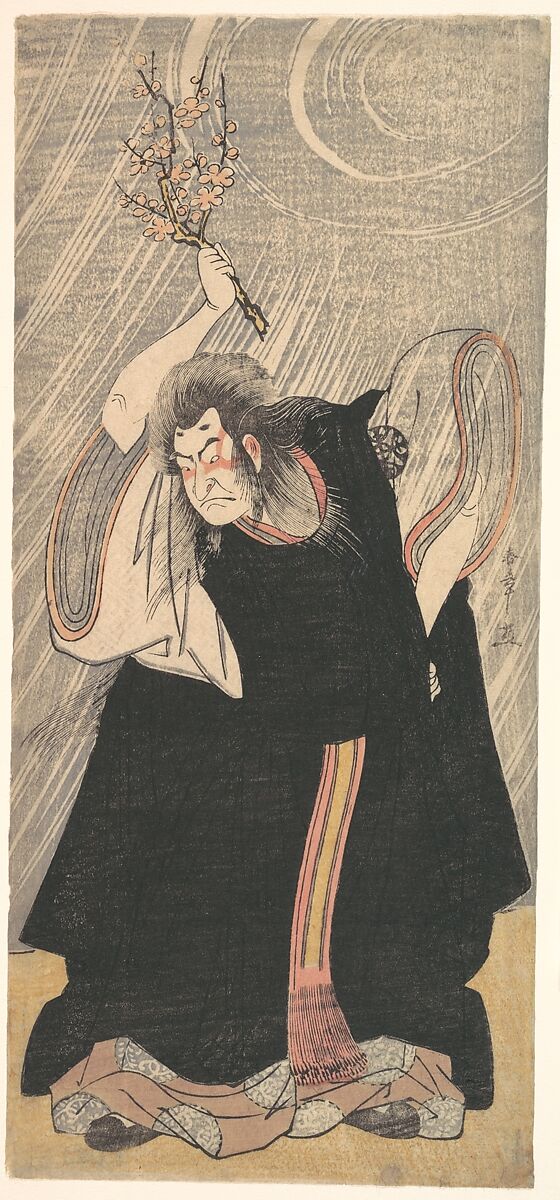

Traditionally, kabuki signboards and actor portraits were the exclusive domain of the Torii school, a family tradition. However, their depictions of actors’ faces and gestures were formulaic and monotonous, leaving the townspeople to imagine what the actors truly looked like. It was in Horeki (宝暦) 13 that Shunsho appeared like a comet, around the age of 37.

Shunsho’s actor portraits were so lifelike that viewers could recognise the actors even without their names. These prints captivated the hearts of the common people — much like today’s celebrity photo cards. In doing so, Shunsho opened up an entirely new frontier in ukiyo-e: realistic actor likenesses. For actors, too, these prints became products that boosted their popularity. As a result, commissions for Shunsho increased, and he went on to portray leading performers such as Ichikawa Danjuro V (五世市川團十郎) and Segawa Kikunojo III (三世瀬川菊之丞). In this way, Shunsho established himself as the foremost authority in actor prints and joined the ranks of the most celebrated ukiyo-e artists.

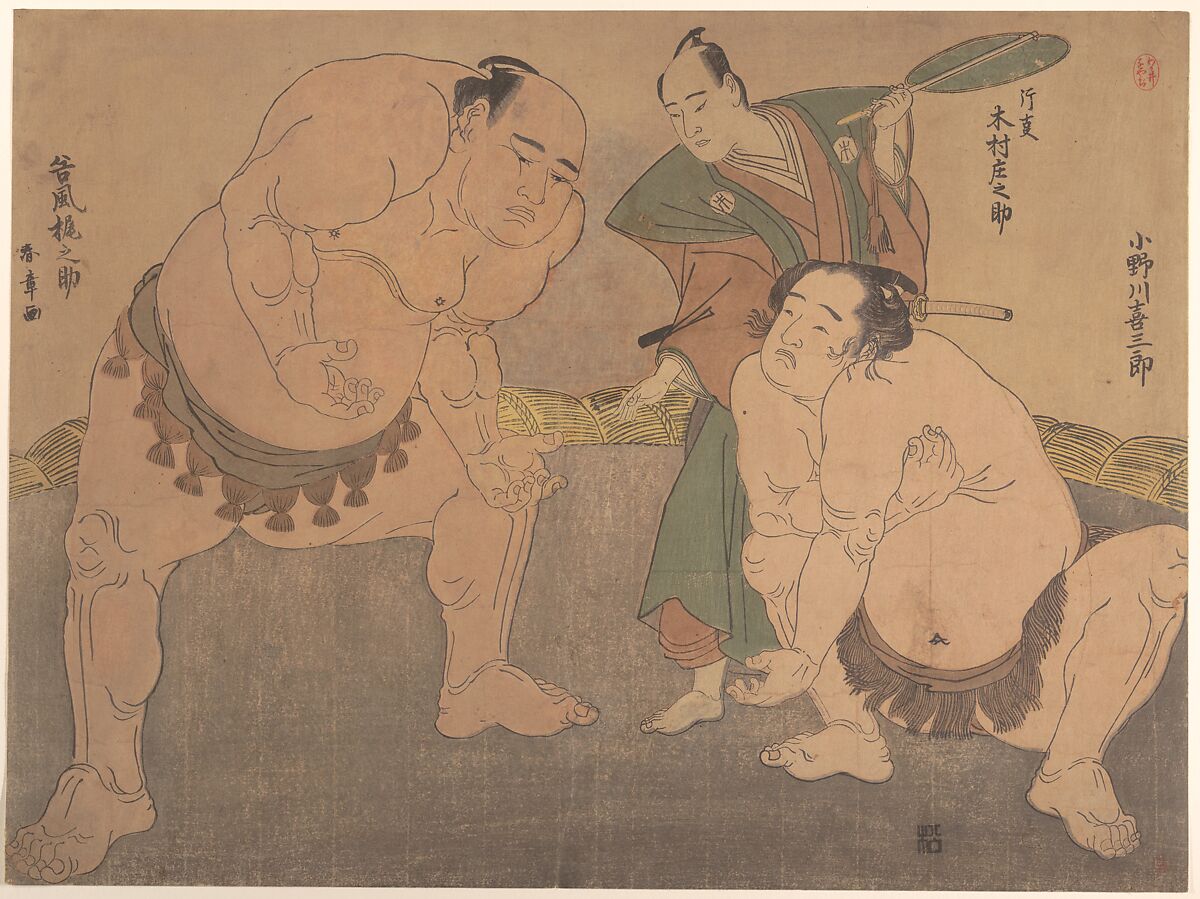

Shunsho’s Sumo Prints: the birth of a new genre

Another body of work that cemented Shunsho’s popularity was his ‘sumo prints (相撲絵)’. Much like kabuki, sumo — especially benefit matches held at venues such as the Ekoin Temple in Ryogoku (両国回向院) — had become a form of popular entertainment for the townspeople. Portraits of sumo wrestlers, who had grown familiar and beloved through their ring-entering ceremonies, became a major hit. From the Tenmei (天明) era onwards (1781–1789), sumo prints became established as a new genre within ukiyo-e. It is no exaggeration to say that Shunsho was the one who laid the foundations for the sumo prints still familiar today.

The ukiyo-e superstar: Katsushika Hokusai’s first master

In the 7th year of Anei (安永, 1778), at the age of 19, Katsushika Hokusai began his artistic apprenticeship under Shunsho. The sumo wrestler illustrations that appear in Hokusai Manga and other works seem to bear strong influence from Shunsho. Among the Katsukawa school, Hokusai quickly distinguished himself, and Shunsho took great care of him, giving him the artist name Katsukawa Shunro (勝川春朗). Under this name, Hokusai made his professional debut as an illustrator for Yoshiwara Saiken (吉原細見, a guide to Yoshiwara)*6.

However, after Shunsho’s death, Hokusai, who did not get along with his fellow disciples, left the Katsukawa school and struck out on his own. For Hokusai, who later belonged to no particular school, meeting Shunsho must have been a pivotal moment in his career as an ukiyo-e artist.

A man of many talents: from picture books and shunga to hand-painted works

Though Shunsho secured his position as the leading artist of kabuki actor portraits, he had already been involved in numerous other projects, including illustrations for picture books.

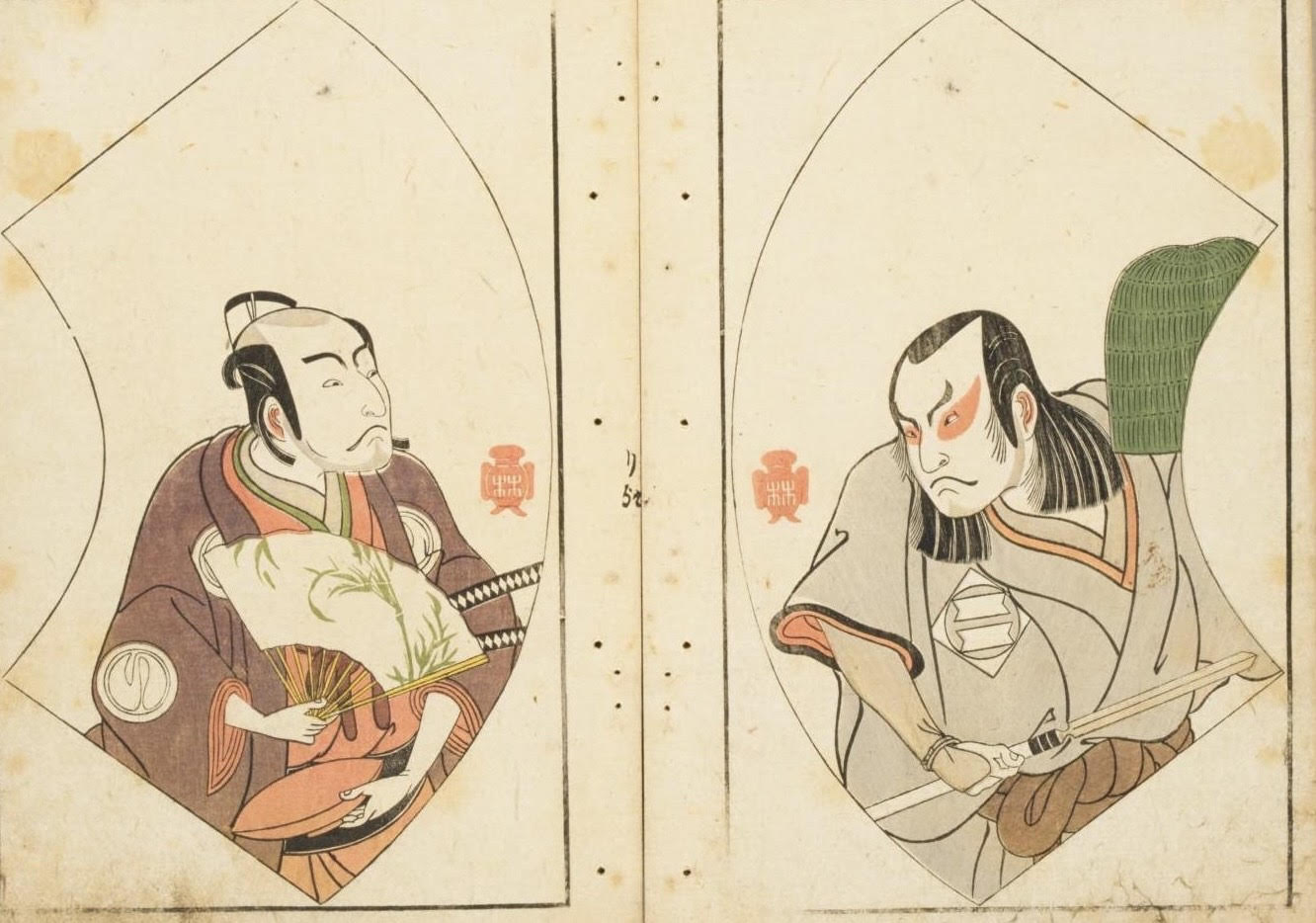

In the 7th year of Meiwa (明和, 1770), he collaborated with Ippitsusai Buncho (一筆斎文調)*7 on Ehon Butai ogi (絵本舞台扇), which became a bestseller with all 1,000 copies selling out.

At the time, it was common for ukiyo-e artists to produce erotic art, known as shunga (春画). Although Shunsho did not paint beauties in standard ukiyo-e prints, in his shunga works he created many elegant, hand-painted images of women, showcasing his extraordinary versatility with the brush.

Several renowned ukiyo-e artists, including Haruyoshi (春好) and Shun-ei (春英), emerged from under Shunsho’s guidance. His disciples also left behind a wealth of superb prints, many of which are now housed in prestigious collections such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It is truly puzzling that the name of such a talented artist remains relatively unknown. Perhaps he was simply too far ahead of his time. This genius of the early days of ukiyo-e raced through its dawn and ended his life as an artist on the 8th of December, 1792 (Kansei,寛政 4), at the age of 67.

‘Popular Ukiyo-e Artists of Edo: 15 Masters of the Popular and the Artistic’ by Naito Masato (内藤正人), Gentosha Shinsho (幻冬舎新書); ‘Edo Ukiyo-e Artists’ by Fukuda Kazuhiko (福田和彦), Yomiuri Shimbun Publishing; ‘Katsukawa Shunsho’ by Hayashi Yoahikazu (林美一), Kawade Shobo Shinsha (河出書房新社); ‘Sekai Dai-Hyakka Jiten (World Encyclopaedia) Digital Edition’

Header image : Ehon Butai Ogi (絵本舞台扇) – Courtesy of the National Diet Library Digital Archive

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/rock/culture-rock/235764/