The Arimatsu Narumi Shibori Yukata Worn on the Third Day After Giving Birth

My son was born after his due date, during the time of year when the air is at its coldest and crispest. I remember as if it were yesterday how he cried with a vigorous voice, his body larger than most thanks to his long stay in my womb. While I was smiling to myself with the joy of starting “motherhood”—holding him and breastfeeding with unpractised hands—I also harboured anxieties about being faced with so many first-time experiences.

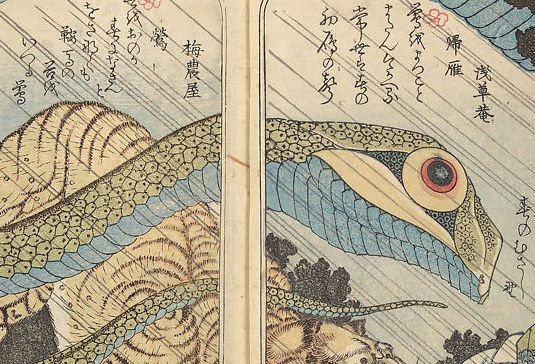

After having stayed in in my postpartum pyjamas in the hospital room, on the third day after delivery, I put on a Yukata, with an indigo-coloured Arimatsu Narumi Shibori pattern (有松鳴海絞り). While I had been thinking of nothing but my son since the moment I woke until I fell asleep, it was only when I put on the yukata that my consciousness suddenly returned to myself; I realised how sleepy I was and that my lower back was aching.

Compared with Western clothing, kimono and yukata involve many more steps to put on. Focusing fully on the act of dressing, even for a short time, often leaves both body and mind feeling refreshed once it’s done—and I’ve never felt that more clearly than in that moment.

By tending to the body, the mind naturally settles as well. It feels akin to meditation, and I see it as one of the mindful qualities inherent in kimono culture.

Combed Cotton Is Ideal for ‘Child-rearing Kimono’

After being discharged from the hospital, the true struggle of child-rearing began, and this brought a major change to my kimono life. The primary premise for choosing a kimono shifted to “something that feels good and won’t cause a rash even if it touches my son’s sensitive skin” and “something I can hold him tight in without worrying about wrinkles.” Furthermore, it had to be “something I can toss in the washing machine immediately if milk is spilt.” These became my non-negotiable criteria when choosing kimono or yukata.

The item that proved exceptionally useful for daily wear was the Men-koma (綿コーマ; combed cotton) yukata. Men-koma is a plain-weave fabric made from durable combed cotton yarn. Woven with yarn that is strong, has little fuzz, and is uniform in thickness, the fabric is characterised by a soft, moist texture that feels incredibly comfortable against the skin.

It was especially wonderful after taking a bath. Back then, after stepping out of the bath, I was so preoccupied with my son that I didn’t have the luxury of fastening buttons one by one. A yukata—which I could throw on like a towel and simply tie with a cord—was perfect.

This makes sense when you trace back the origins of the yukata. While commonly seen at festivals and fireworks displays today, the origin of the yukata is said to be the Yukatabira (湯帷子), a garment used by aristocrats in the bathhouse during the Heian period. It is said that eventually, commoners also began wearing them after bathing, and indigo-dyed versions became popular as everyday clothing and for strolling around town.

My way of dressing, chosen out of desperation during childcare by prioritising function, was actually a distillation of ancestral wisdom, refined and honed over time.

The Obi That Stabilised My Unstable Postpartum Body

Around this time, I often wore a Hakata-ori (博多織) hanhaba-obi (半幅帯; half-width sash). Among these, I have long loved the Kenjo-gara (献上柄)—a pattern based on Buddhist ritual implements that was presented as a gift to the Shogunate during the Edo period. The reason I never tire of it is its modern air despite being a traditional motif.

Furthermore, its suppleness—achieved by using a large number of warp threads—and the excellent comfort of a fit that never loosens once tightened are superb. The unique kinunari (絹鳴り; silk squeak), the “kyu-kyu” sound made when the silk surfaces rub together during tightening, is another feature unlike any other. I found support for my still-unsteady, postnatal body by wrapping an obi around my waist as I held my baby.

There was also a significant change in how I wore my kimono. At first, I worried about the garment becoming disarranged after my child pulled at the chest or after using a baby carrier. However, at some point, I began to feel that those disarrangements were precious memories of my child that could only be experienced in this very moment. The wrinkles in the kimono after a hug are proof of being held with full affection. It is a beauty where a person’s character and daily life appear in their dressed form. I realised that this is a unique charm and ‘flavour,’ different from a perfectly symmetrical and meticulously arranged appearance.

Looking back at photos from that time, my collar and the back of my kimono are always slightly loose, the obi never quite snug. Yet those imperfect silhouettes hold scenes of life with my child as a baby, reflected in the way I was dressed. They are irreplaceable, tender memories—true treasures to me.

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/fashion-kimono/250965/