Known in the 7th century, tiger and leopard furs

There is a poem that I recall every year when the end of the year comes into sight. It is ‘Toshi Meguri (年めぐり)’ by Sakata Hiroo (阪田寛夫, 1925-2005), which appeared in my elementary school Japanese textbook. Beginning with ‘karuta takoage genki na ko (かるた たこあげ げんきなこ= playing cards, kite, cheerful child)’, the poet sings about the seasonal poems of the year in the rhythm of the seven-five syllables. The poem also includes a number of words that, to a twenty-first century city dweller, evoke a kind of nostalgia, such as ‘kirinogeta (きりのげた = lacqured wooden clogs)’ and ‘shikano no koe (deers cry)’.

Among these, however, the one we see the least of all is probably ‘kegawagaito (けがわがいとう=fur coat),’ one of the words that embodies the twelfth month of December. In Japan, the word’ gaito (外套, cloak)’ has been completely replaced by ‘coat’ today, and it is very rare to see people wearing all-fur products in town today, partly due to the spread of the animal rights movement and the improved properties of artificial fur.

However, if we go back in history, fur, with its excellent protection against cold and beautiful patterns and fur, has been loved by many people in Japan since ancient times. ‘Nihon syoki (日本書紀, the Chronicles of Japan),’ a history book compiled in the Nara period, mentions that in the 15th year of the Emperor Temmu (天武, 686), an envoy from Silla on the Korean Peninsula brought ‘ kohyogawa (虎豹皮, toratiger and leopard skins)’ along with various treasures and textiles.

Although tigers and leopards appear in various Chinese and Buddhist scriptures, they are not native to Japan. However, because of their beautiful patterns, their pelts were highly prized in Japan during the Nara and Heian periods. According to the ‘Engishiki (延喜式),’ a Heian-period ritual book, tiger skins were only to be worn by officials of the fifth rank and above, while leopard skins were only to be worn by councilors and above.

It is interesting that tiger and leopard skins are already strictly distinguished, but councilors and above are high-ranking officials who would be considered cabinet members today. In ancient society, leopard skins were a luxury item that could only be used by a very few people.

What the fur that Suetsumuhana was wearing meant

Nagaya-o (長屋王), a member of the imperial family who held the important position of Sadaiji (左大臣 = Minister of the left) during the reign of Emperor Shomu (聖武天皇) in the Nara Period, is known for a huge amount of mokkan (木簡= wooden writing tablet) excavated from the ruins of his mansion. Among these wooden tablets, there is actually one that is inscribed with ‘ hyogawa mon roppyaku mon (豹皮文六百文). This seems to be a record of the purchase by the Nagaya Kings of imports from Bohai Province (a country located from present-day northeastern China to the northern part of the Korean Peninsula), which was the largest source of fur for Japan at the time. The fact that the number of furs presented by the envoy from Balhae in 741, shortly after the Nagaya Kings were driven to death by a political upheaval, was not so many as ‘seven strips of tiger skin, seven strips of bear skin, and six strips of leopard skin’ reminds us that these items were quite expensive.

In the early Heian period, Prince Shigeakirasinno, a son of Emperor Daigo (醍醐天皇), surprised the Japanese envoys to Japan by wearing an eight-piece Kuroten no Kyu (黒貂の裘), a fur coat made of leather). Kuroten, along with tiger and leopard skins, were imported from Balhae in great numbers, but what is interesting is that the Balhae envoy actually brought only one kyu fur coat with him. It is said that the envoy was very embarrassed because of this. It is interesting to note that the fur played an effective role as a tool for informing people of one’s wealth.

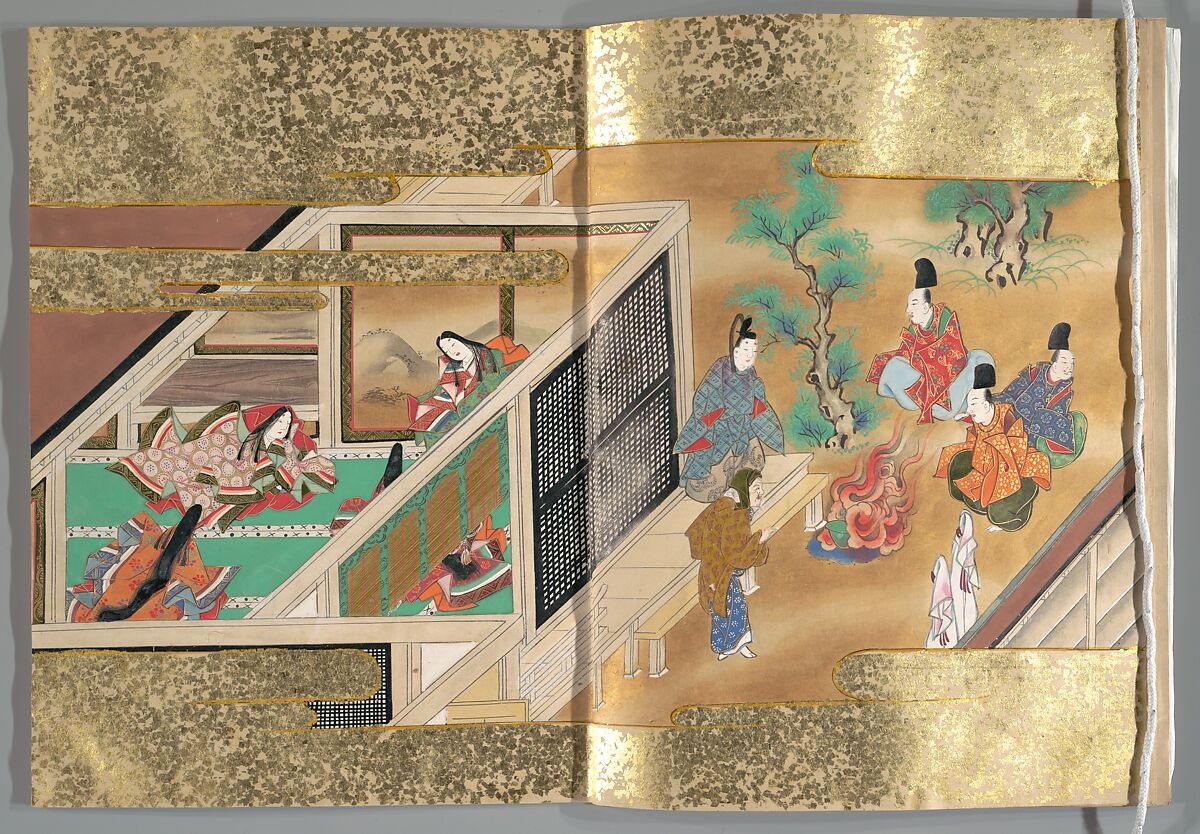

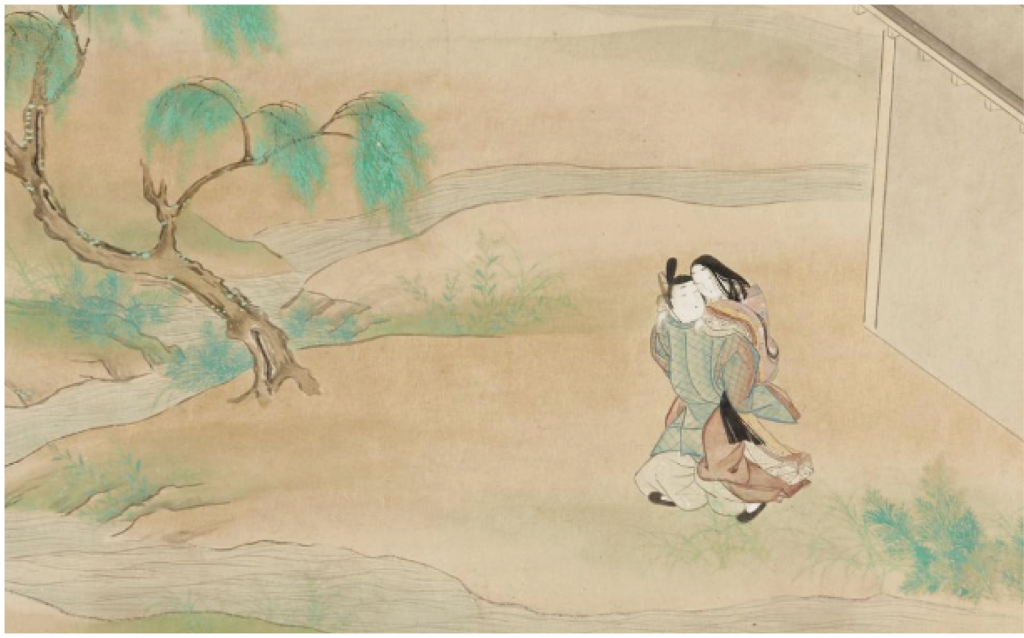

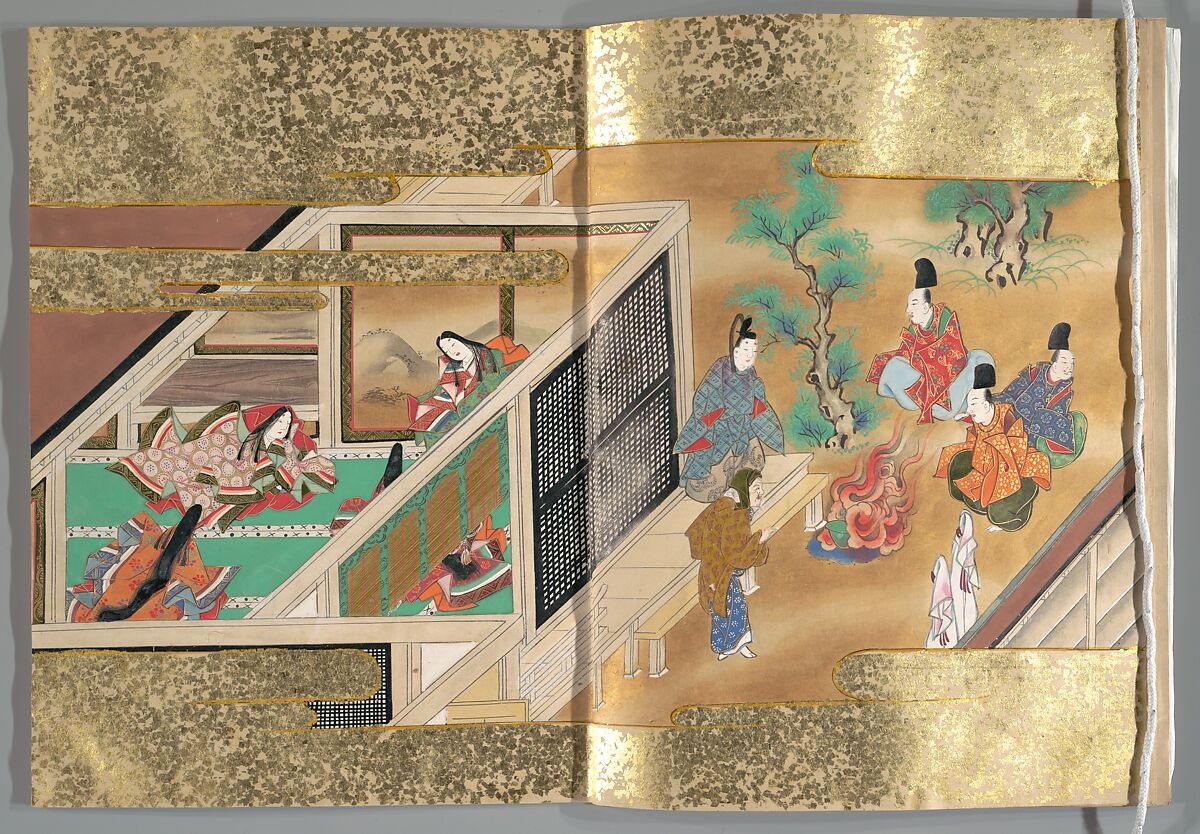

However, just as there is always a time and a place for what to wear even today, wearing furs was not always praised in the Heian period, no matter how expensive they were. In ‘Genji monogatari (源氏物語, The Tale of Genji)’ written by Murasaki Shikibu (紫式部), Suetsumuhana (末摘花), a princess of the fallen imperial family, appears wearing ‘a black marten skin robe for the outer garment, which is the most beautiful and fragrant of the juni-hitoe (十二単), with a black marten fur robe laden with fragrance (表着には黒貂の皮衣、いときよらに香ばしき).

Suetsumuhana is depicted as the most unattractive character in ‘Genji monogatari’. Moreover, inside her kuroten’s fur robe, she wears an extremely faded kasane (襲= layers of garments) and a soiled uchiki (underskirt), a rather odd combination. By depicting only the kuroten’s fur as beautiful and out of place, Murasaki Shikibu symbolically expresses the prosperity of the family during her father’s lifetime.

Genji looked at the Suetsumuhana and said,

“It looks ostentatious and inappropriate for a young woman to wear. Though, It must be very cold without this fur.”

He muttered to oneself. The young woman may have been dressed to the nines, but she was reminded of the difficulty of handling furs, now and in the past.

In her essay ‘Makuranososhi (枕草子),’ Seishonagon (清少納言), who lived at about the same time as Murasaki Shikibu, mentions ‘ura mada tukenu kawaginu no nuime (裏まだつけぬかわぎぬの縫い目, a leather garment with no lining)’ as one of the ‘mutsukasigenarumono (むつかしげなるもの, things that make one feel uncomfortable)’. The fur, which is made of a stiff fabric and must be sewn roughly with a thick needle, would certainly be seen as very shabby on its own. It is surprising that Seishonagon’s keen eye noticed the gap, which is even more noticeable when the leather garment is beautiful and expensive.

Furs burned by Princess Kaguya

Now, the most famous leather robe of the Heian period is probably the ‘Hinezumi no kawagoromo (火鼠の皮衣 = fire-rat fur coat)’ from ‘Taketori Monogatari(竹取物語)’.

Hinezumi, the fire rat is an imaginary animal, a white rat that lives in the fires of volcanic countries in the south of the continent. According to one theory, it weighs 1,000 pounds (about 600 kg) and its fur is 2 shaku (尺) (about 60 cm) long, making it a rather large animal for a rat.

It was believed that the fur of the fire-rat would not burn in a fire, and Kaguya hime, who was born from a bamboo, demanded this from Abe no Miushi (阿部御主人), one of her five suitors. Miushi not willing to pay any price, sends a messenger to a trader in Tang China to buy a fire-rat fur coat, but the trader tells him how expensive and precious the item is, and even tries to raise the price. Thanks to the merchant’s efforts, the supposedly fire-rat fur coat arrives safely in Miushi’s possession, but the princess puts the robe on fire to see if it is genuine, and as a result, it burns to a crisp.

However, even if the fur was not a fire-rat fur coat, according to the description in ‘Taketori Monogatari ‘, the skin robe that came from Tang China was ‘deep blue in colour, the edges of the fur shining with gold, and its magnificence could not be compared.’ It is hard to imagine a real animal in blue and gold, so the fur was probably dyed by hand. Considering the fact that fur itself was expensive, it must be assumed that the fur coat itself was also quite valuable, no matter how fake it was.

‘Taketori Monogatari’ describes Abe no Miushi as having ‘kao wa kusa no ha no iro nite itamaheri (顔は草の葉の色にていたまへり, his face was pale like a grass’ when the item he had spent so much money on was burnt. Reading the story again after learning about fur in the Heian period, one cannot help but think that Kaguyahime’s behavior was somewhat excessive. ……

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/229453/