In current times, setsubun (節分) refers to the day before the beginning of spring, around February 3rd. As the name suggests, setsubun literally means the division of seasons. Since Japan has four seasons, originally there were four setsubun celebrations each year. In this article, we will explore why only the setsubun before the beginning of spring has remained an essential annual event, and why customs like throwing beans and eating eho-maki (恵方巻) have become traditions.

Setsubun falls on the day before the beginning of – but had this also coincided with new year’s eve in the past?

In the nijushi sekki (二十四節気, traditional 24 solar terms), each of the four seasons has six points marking the change of the season. Setsubun occurs the day before the beginning of the seasons: risshun (立春, start of spring), rikka (立夏, start of summer), risshu (立秋, start of autumn), and ritto (立冬, start of winter). It was believed that changes in the seasons brought about the potential for evil spirits, and thus the custom of monoimi (物忌み) —avoiding outings and being cautious from evening onwards—was practiced from ancient times.

The reason setsubun on the day before risshun became a seasonal event is related to the old lunar calendar, which was used until the 5th year of the Meiji era. In the current solar calendar, Risshun falls around February 4th, but in the old lunar calendar, it coincided with the New Year period. Therefore, risshun carried the dual meaning of both the beginning of spring and the start of the New Year. This means that setsubun, occurring the day before risshun, was essentially New Year’s Eve. Consequently, events like bean throwing and eating eho-maki sushi rolls during setsubun are heavily influenced by New Year traditions.

Warding off evils – the reason behind bean throwing at setsubun

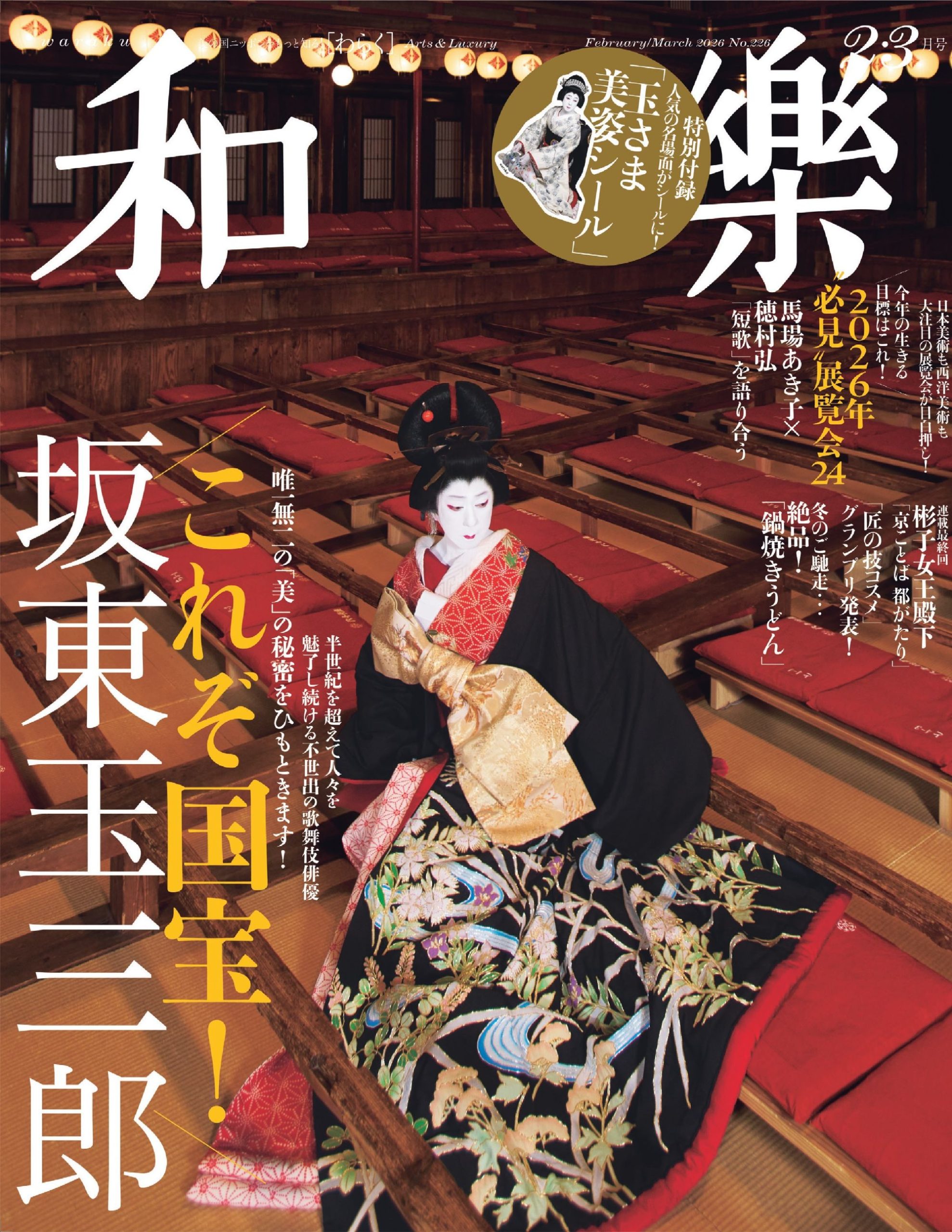

When we think of setsubun, we often think of throwing beans. The tradition of placing roasted soybeans into a tray and shouting “Oni wa soto (鬼は外), fuku wa uchi (福は内)” (Out with the evils, in with good fortune) to drive away demons is practised throughout Japan. This ritual, intended to pray for the warding off of disasters and illness, traces its origins to the tsuina (追儺, demon expulsion) or oniyarai (鬼やらい, demon-chasing) ceremonies held at the imperial court until the Middle Ages. The current form of the setsubun event, however, developed after the Muromachi period.

The beans used for this ritual are also called fukumame (福豆, lucky beans), as beans were long believed to possess the power to repel evil. It is said that if you pick up and eat as many beans as your age, you will spend the year in good health. In some traditions, it’s also recommended to eat one more than your age, as in the past, people followed the kazoedoshi (数え年) system where one was considered to be one year old at birth, and age was added at New Year, rather than on a birthday.

*Chiyoda no Ooku (千代田之大奥), Setsubun (節分) by Yoshu Chikanobu (楊洲周延) (from the National Diet Library Digital Collections)

Warding off demons with smelly sardines and spiky holly?

Additionally, during setsubun, there was a custom of sticking the heads of grilled sardines (iwashi; 鰯) or cut rice cakes onto hiiragi (ひいらぎ, holly) branches and decorating the gate or front door with them. The strong smell of sardines was thought to drive away demons, and it was also believed that the sharp holly leaves could pierce the eyes of any demons drawn by the sardines or rice cakes.

The tradition of finding sardines in supermarkets on setsubun day is a remnant of this practice. It’s an intriguing thought—whether enjoying fresh, non-smelly sardines for dinner would still help keep demons at bay!

The eho-maki trend dates back to the edo period

It may seem like the tradition of eating eho-maki sushi roll has only recently gained popularity, and that perhaps we’re all being swept up in the setsubun marketing hype. The custom of eating a whole futomaki (太巻き, thick sushi roll) silently while facing the eho (恵方, the lucky direction for that year) did indeed spread in Kansai around the 1970s and became widespread across Japan during the Heisei period. While the exact origin is debated, it’s said that the Osaka seaweed merchant association played a role in promoting it.

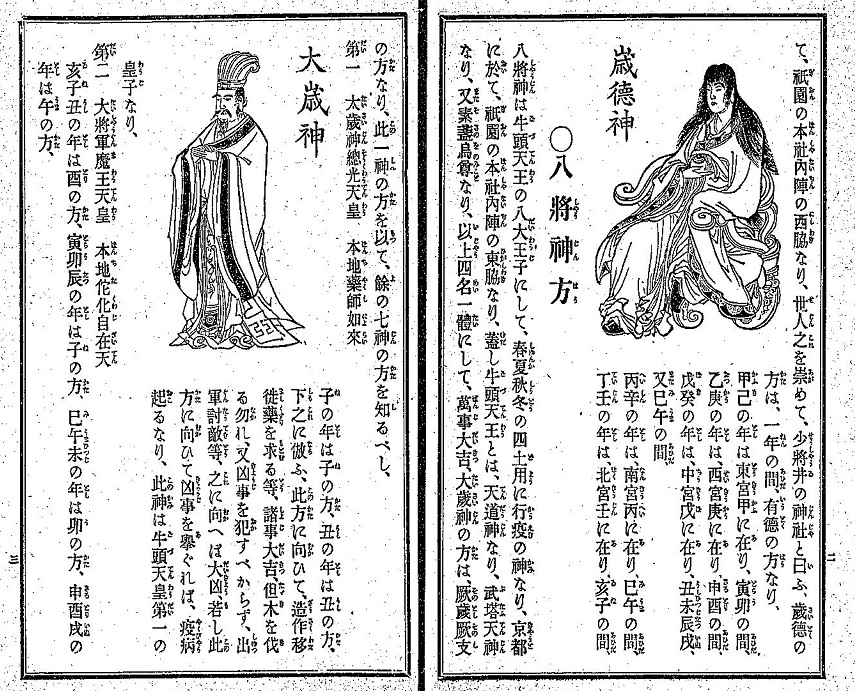

However, the practice of paying attention to the eho direction goes back much further. During the Edo period, it was believed that the toshigamisama (年神様, New Year’s deity) would come from the eho direction to bless the household. The wood used for the New Year’s kadomatsu (門松, door decoration) was said to be freely gathered from mountains in the eho direction.

Shunsho ehomode (春曙恵方詣) by Kochoro Toyokuni (香蝶楼豊国) and Ichiyosai Toyokuni (一陽斎豊国) (from the National Diet Library Digital Collections)

Abe Seimei hoki nai den zukai (安部晴明簠簋内伝図解) by Karasawa Shokaku (柄沢照覚) (from the National Diet Library Digital Collections).

Setsubun falls on 3 February… But not always

You may have noticed that we say “Setsubun falls around 3 February” rather vaguely. This is because the start of spring can shift from 4 February. Some may remember that in 2021, Setsubun fell on 2 February instead of 3 February. According to the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, this was the first time in 37 years that Setsubun did not fall on 3 February, with the last instance being in 1984 (4 February).

The 24 solar terms divide the sun’s apparent path in the sky (ecliptic) into 24 equal parts of 15 degrees each, serving as seasonal markers. While the modern calendar counts a year as 365 days, the Earth actually takes approximately 365 days and 6 hours to orbit the sun. This discrepancy causes the timing of the solar terms to shift slightly each year (leap years, which add an extra day every four years, help to adjust for this).

It’s a bit complicated, isn’t it? But the 24 solar terms played such a practical role that it’s worth delving a little deeper.

The 24 solar terms: a guide for agricultural work

Before the adoption of the Gregorian calendar (solar calendar) in the 6th year of Meiji (1873), Japan used the lunisolar calendar, which occasionally included an intercalary month, resulting in a 13-month year. To ensure that the seasons could still be marked accurately despite the varying length of the year, the system of nijushi sekki (24 solar terms) was introduced. These markers include events such as toji (冬至, the winter solstice when the day is shortest), geshi (夏至, the summer solstice when the day is longest), and shumbun, shubun (春分・秋分, the spring and autumnal equinoxes).

Even under the lunisolar calendar, the dates of the nijushi sekki were not fixed. In fact, the Kokin Wakashu (古今和歌集, collection of ancient and modern japanese poetry) includes a poem composed on the day when beginning of spring arrived before the New Year began:

Toshi no uchi ni haru ha kinikeri hitotose wo kozo toya ihamu kotoshi toya ihamu (年のうちに春は来にけり一年を 去年とや言はむ今年とや言はむ)

Meaning: Before the year ends, spring has come—How should we name this year? Shall we call it last year or this year?

Kokin Wakashu (古今和歌集), Ariwara no Motokata (在原元方)

It’s fascinating to see how nijushi sekki have remained a part of daily life from the Heian period to the present day. While originally developed in ancient China, the system has been adapted for Japan, where it has long been used as a guide for agricultural activities, even though there are slight differences between the seasons in China and Japan.

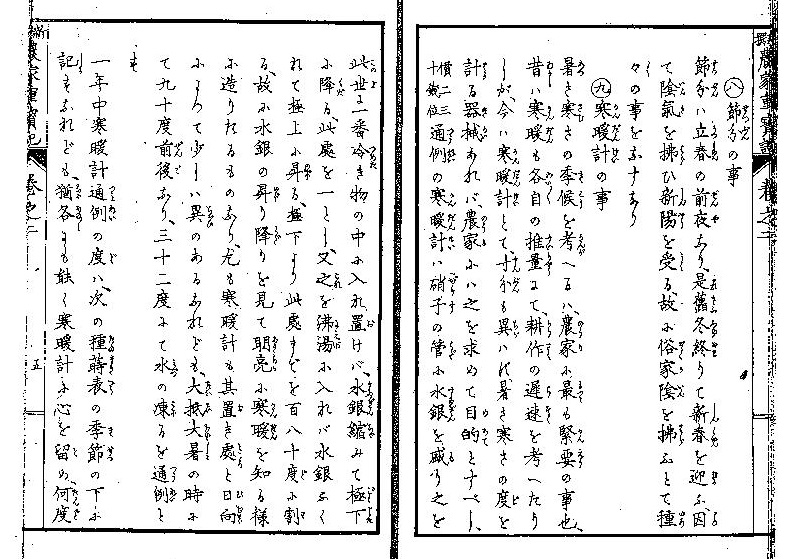

Although setsubun is classified as a zassetsu (雑節, seasonal marker outside the nijushi sekki), it is clearly described in practical Edo-period texts like the Shinsen noka chohoki (新撰農家重宝記, newly selected farmer’s treasures):

‘Setsubun marks the end of winter and the beginning of spring, a shift from yin to yang.’

Understanding the meaning of setsubun brings a refreshing sense of closure to winter, allowing us to embrace the arrival of risshun with a lighter heart. Isn’t that wonderful?

Shinsen noka chohoki (新撰農家重宝記), first volume, part 2, by Aoki Sukekiyoshi (青木輔清) (From the National Diet Library Digital Collection)

References:

Japan encyclopedia (Nipponica)

World Encyclopedia

Heisei nippon seikatsu benri tyo (平成ニッポン生活便利帳)

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/rock/culture-rock/187630/