What exactly are oni, the villains of folktales?

The Oni (鬼, demon like supernatural creatures from japanese folk-lore) that appear in picture books, setsubun (節分) bean-throwing traditions, and legends across Japan are arguably the country’s most famous yokai (妖怪, supernatural beings). When you think of oni, you might picture them wielding spiked clubs, wearing leopard-print loincloths, sporting horns, and having bodies painted in red or blue.

While oni are associated with yokai in Japan, in China, the term oni is more closely tied to the image of ghosts. This is because, in ancient Chinese beliefs, oni were considered the spirits of the dead.

There are various theories about the origin of the word ‘oni’. Some suggest it derives from the yin (陰) of the ancient Chinese philosophy of yin-yang (onmyodo (陰陽道) in Japan). Others propose it comes from ongyo (隠形), meaning ‘invisible spirit’ or ‘hidden form,’ with on (隠, hidden) evolving into oni. As the etymology suggests, oni were once thought to be terrifying precisely because they were unseen, lacking any fixed or visible form.

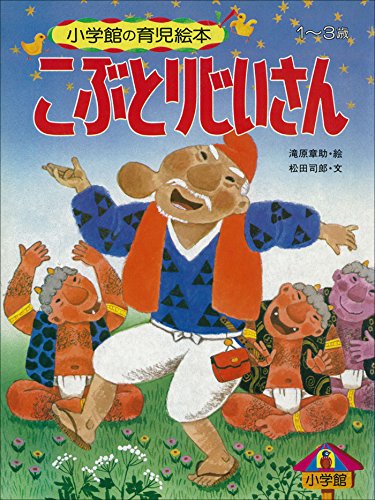

The curious oni in the folk tale ‘Kotoburi Jiisan’

Many Japanese folktales feature oni, making them familiar to almost everyone in Japan through picture books, anime, and other media. One of the most iconic stories involving oni is Kobutori Jiisan (こぶとり爺さん, The old man with a lump). The highlight of the story is undoubtedly the scene where the old man dances with the oni. While oni are usually cast as villains, here they transform into jovial yokai, reveling in dance and celebration.

The origins of Kobutori Jiisan can be traced back to the Uji Shui Monogatari (宇治拾遺物語), a collection of folktales compiled in the early Kamakura period. The storyline is almost identical to the modern version, but the oni in the original are uniquely striking.

In the tale, an old man caught in a storm in the mountains takes shelter in the hollow of a tree for the night. As he prepares to rest, a group of oni appears, and their appearances are quite eccentric. Their skin comes in vibrant hues—some have bright red skin and wear blue robes, while others have black skin paired with red garments. Some are dressed only in loincloths, others have no mouths, and some even have a single eye.

The sheer variety of these oni is astonishing, revealing a richness of design one might not expect. About a hundred of these peculiar creatures gather, forming a circle and throwing a grand feast. The sight leaves the old man utterly astonished.

What’s the difference between red oni and blue oni?

While red and blue oni are the most commonly seen in folktales, such as in Kobutori Jiisan, the story also features a rare black oni. And if there’s a black oni, it’s only natural that there are oni in other colours too.

During setsubun bean-throwing rituals, red and blue oni are the traditional go-to colours. However, in addition to red and blue, there are also yellow (or white), green, and black oni—making up a total of five types. Setsubun oni are said to typically come in five colours, a concept rooted in the Buddhist teaching of the Five Hindrances (Gogai, 五蓋), which represent five obstacles that bind the human mind.

The five colours of the oni during setsubun symbolise these human hindrances, with each shade representing a different type of mental burden or desire.

Five colour variations representing the oni’s personalities

The five colours of oni—red, blue, yellow, green, and black—may appear as vibrant as a team of superhero characters, but these shades are more than just skin-deep. The colours of oni are deeply rooted in Buddhist teachings and the principles of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements (Onmyo Gogyo, 陰陽五行説)

The red oni symbolises greed (tonyoku, 貪欲), one of the Five Hindrances. This oni represents desire and craving. The iconic oni wielding the spiked club, famous from the phrase ‘oni ni kanabo (鬼に金棒),’ embodies this trait.

The blue oni represents anger (shinni, 瞋恚), encompassing malice, hatred, and rage. It is said that throwing beans at the blue oni brings happiness and prosperity.

The yellow oni (or white oni) signifies restlessness (joko, 掉挙), representing regret and stubborn attachment. This oni is said to carry a saw.

The green oni symbolises sloth (konchin, 惛沈), which includes sleepiness, laziness, gluttony, and lack of seriousness. Armed with a naginata, beans are thrown at this oni to pray for good health.

The black oni embodies doubt (gi, 疑), wielding an axe and representing mistrust and complaint.

Although oni often have a villainous reputation, the vices they symbolise are familiar to all of us. In ancient times, people may have used the oni during setsubun as a reflection of their own flaws and a reminder to reform. In this sense, the oni’s colours act as mirrors to human nature. By throwing beans, people sought to cast out their root desires and strive to be better individuals.

While oni symbolise desires and malevolence, some oni are kind and bring blessings to humans. In earlier times, oni were regarded as sacred beings. Perhaps the oni who grant human prayers are heroes beyond our understanding.

By the Way, What Colour Were the Oni Defeated by Momotaro?

This is something I’ve always been curious about.

The skin colour of oni carries specific meanings. So naturally, every time I see oni depicted in picture books or scrolls, I can’t help but wonder about the significance of their colours. Depending on the version, the colours vary widely.

In Momotaro, the oni are described as rampaging through nearby villages, stealing treasures and feasts from the people. Judging by their greed and ferocity, one could surmise… the oni defeated by Momotaro were red!

It’s fun to imagine the story this way, adding a layer of symbolism to the classic tale.

※Header image:Courtesy of wikimedia commons

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/rock/culture-rock/103110/