The phrase “Baigaeshi (倍返し, payback double)” became a buzzword thanks to the drama ‘Hanzawa Naoki (半沢直樹)’. In fact, within the series, even more extreme variations like “10-times payback” and “100-times payback” were shouted. Regardless of the multiple, the show thrived on the spirit of revenge—striking back when wronged, staying true to one’s convictions, and forging ahead on one’s own path.

In some cases, even bowing down in submission to your superiors was seen as acceptable if it served a greater purpose. In a country where the corporate world is particularly rife with excessive deference and employees who dare not speak out, Hanzawa Naoki provided an exhilarating catharsis. It’s no surprise that the show became a social phenomenon in Japan at the time of its broadcast.

From a manager’s perspective, however, this is hardly reassuring. Without realising it, one could become the target of a subordinate’s silent grudge, subjected to their own version of Baigaeshi. This bears an uncanny resemblance to the gekokujo (下克上, overthrow of superiors) seen during the Sengoku (戦国) period. In today’s Japan, such grievances might result in a workplace harassment lawsuit, but in the warring states era, they could lead to outright rebellion—a far more perilous consequence.

With that in mind, this article explores the techniques that Sengoku-era commanders used to maintain loyalty and prevent betrayal. It wasn’t just subordinates who had to navigate treacherous waters; even rulers had to exercise careful diplomacy. Let’s take a closer look at their unspoken cries for trust and unity. We present the master tacticians’ ultimate strategies for fostering loyalty—delivered in the form of laws to follow.

Rule 1: Honour not just your vassals, but their parents too

The first rule is this:

“Honour not just your vassals, but their parents too.”

Every vassal has a family, and this method hinges on that very fact. Instead of focusing solely on winning over the vassal, the key is to gain favour with those around them first—an unconventional but effective approach. One of the most famous figures to put this strategy into practice was none other than Uesugi Kenshin (上杉謙信), the ‘Echigo no tora (越後の虎, Tiger of Echigo)’.

It all began with the reckless actions of a group of young samurai.

In July 1573, Kenshin led his forces into Etchu (越中) Province (modern-day Toyama Prefecture), crushing Jinbo Nagamoto (神保長職) and the Ikko-ikki (一向一揆) forces. His momentum carried him towards Kaga (加賀) Province (modern-day Ishikawa Prefecture), but he soon encountered an unexpected obstacle. The Asahiyama (朝日山城) Castle in present-day Kanazawa, a stronghold built by the Ikko-ikki in preparation for Kenshin’s advance, fiercely resisted his siege.

Statue of Uesugi Kenshin (上杉謙信)

Some accounts suggest that a significant number of guns had been supplied to the castle from Negoro (根来) in Kishu (紀州) Province. With gunfire raining down from the fortress, Kenshin’s troops struggled to advance. Frustrated by the stalemate, a few impulsive young samurai in his army could no longer hold back. Did they believe their youthful vigour alone would carry them through? Or were they simply eager to distinguish themselves in battle? Whatever their reasoning, several of them acted on their own accord and approached the enemy fortifications. As expected, they were immediately met with a hail of gunfire, resulting in casualties. Upon hearing of this, Kenshin was furious. He swiftly ordered the reckless samurai to be captured and placed in confinement.

Ordinarily, the matter would have ended there. The hot-headed young warriors had broken ranks and acted without orders—confinement was a fitting punishment. They themselves could hardly complain; regardless of their intentions, their misjudgement had led to unnecessary losses. Their actions were driven by overconfidence, perhaps even pure ego.

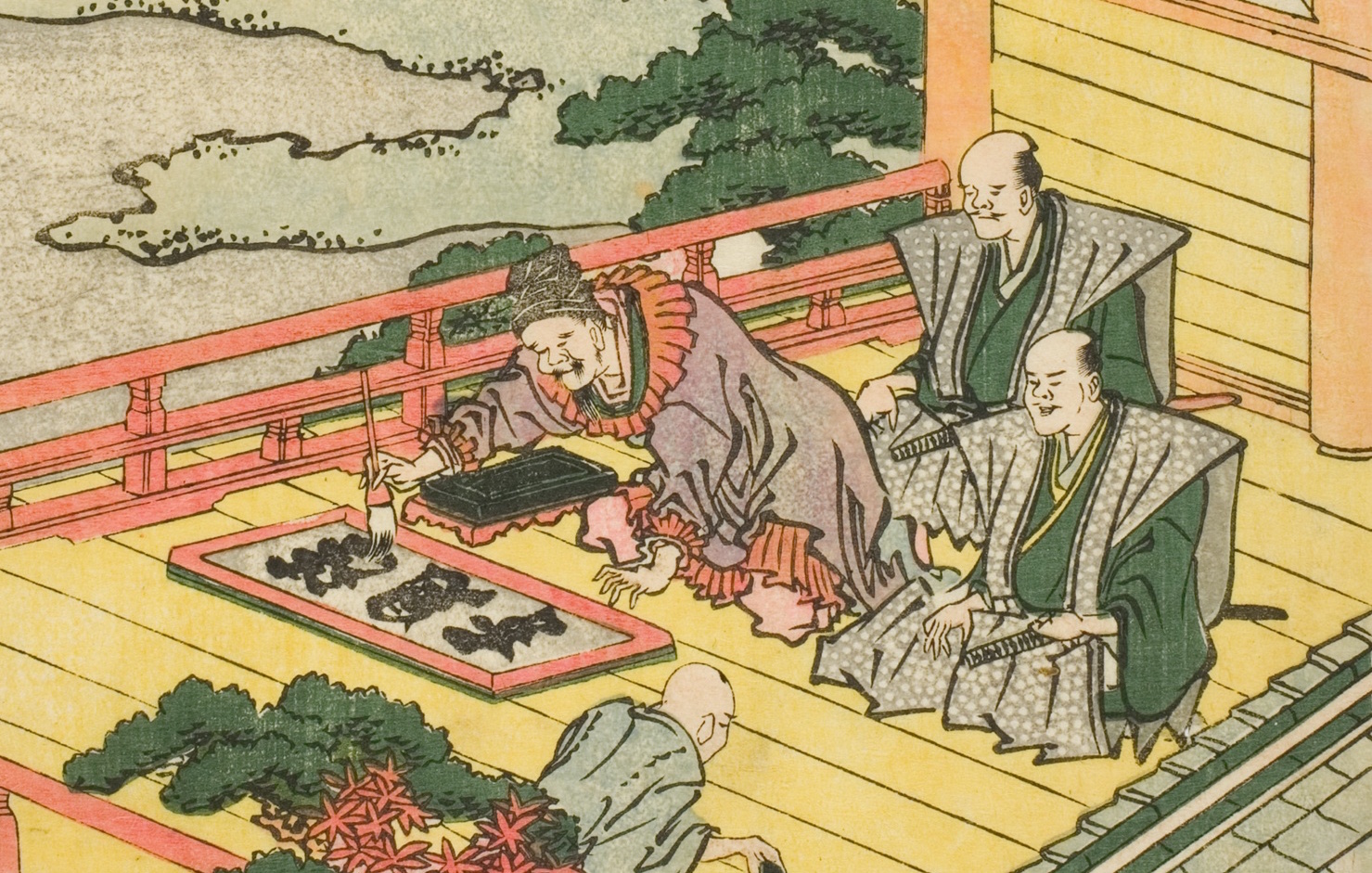

But Kenshin took an unexpected step. He did not stop at punishing the offenders—he also reached out to their parents. A surviving letter, preserved in the ‘Dewa Yoshie (出羽吉江) Documents’, was addressed to Yoshie Oribesuke Kagesuke (吉江織部助景資), a senior retainer of the Uesugi clan, and his wife. Kenshin wrote:

“Your son ignored my counsel and recklessly ran alone in front of enemy gunfire. I commanded my men to drag him back, and he is now being held in confinement. You must be deeply worried, but had I allowed them to face enemy gunfire before my very eyes, only to see them wounded or killed, you would have surely cursed this Kenshin. Therefore, I have confined them for their own good. I hope you will understand my intentions.”

(Excerpt from ‘Sengokubusho ni manabu kyukyoku no manejimento (戦国武将に学ぶ究極のマネジメント)’ by Futaki Kenichi (二木謙一))

Even in the Sengoku period, a parent’s concern for their child was universal. The thought of their son being captured and confined by his own lord would have been unbearable. Kenshin understood this well, and so he wrote to reassure them. To win over a vassal’s loyalty, one must first gain the trust of their parents. This was one of Kenshin’s unique and highly effective methods of leadership.

Rule 2: Master the art of one to one management

In the business world, ‘one to one’ is hardly a new concept. It has long been a staple in management discussions, appearing in phrases like ‘one to one meetings’ and ‘one to one marketing’.

At its core, it simply means one-on-one interaction—focusing on the individual. It’s a practice widely recognised in modern workplaces. And while it would be tempting to say that this approach was common in the Sengoku period as well, the sheer number of soldiers under a general’s command made it challenging. However, there were some exceptional warlords who made a point of engaging with their retainers on a personal level.

That brings us to the second rule:

‘Master the art of one to one management.’

Two notable figures who practised this were Shimazu Yoshihiro (島津義弘), the fearsome ‘Oni-Shimazu (鬼島津)’ of Kyushu, and Mori Motonari (毛利元就), the cunning strategist of western Japan, known for his famous ‘Three Arrows’ lesson.

Shimazu Yoshihiro

Observing the other party closely, choosing words carefully, and adapting one’s approach accordingly—both warlords placed great importance on these principles. However, this is easier said than done. To consistently engage with subordinates on an individual level requires both a strong sense of responsibility and a level of composure not easily maintained in times of war.

The Gojiki (御自記), a historical record of the Shimazu clan, contains anecdotes about Yoshihiro’s attentiveness towards his retainers. He made a habit of encouraging them in a personal and meaningful way. For instance, when the son of a retainer first entered service, he would say:

“You resemble your father. No doubt you will be just as capable as he was.”

This simple remark not only motivated the son but also instilled pride in the father. However, some young warriors had yet to distinguish themselves in battle. In such cases, Yoshihiro would adjust his words accordingly:

“You have not had the fortune to achieve merit yet, but I see great promise in you—perhaps even greater than your father. I expect to see fine deeds from you in the future.”

By tailoring his words to each individual’s circumstances, he strengthened their loyalty.

Similarly, a comparable story about Mori Motonari appears in ‘The Biography of Mori Motonari’. Motonari firmly believed that people naturally develop loyalty towards those they frequently interact with. If a commander remained distant and aloof, never speaking directly to lower-ranking samurai, how could he expect them to feel any loyalty towards him? More likely, they would feel closer to their direct superiors—the officers who regularly gave them orders. Indeed, this rings true even in modern workplaces. Loyalty doesn’t form in a vacuum; it arises through personal connections.

Holding this belief, Motonari made sure to treat all his retainers equally, greeting them warmly and engaging with them personally. He even took extra steps when interacting with lower-ranking warriors. Before meeting them, he would prepare sake and rice cakes in advance. For those who enjoyed drinking, he would say:

“Sake is a wonderful thing—it warms the body in the cold, and in both wartime and peacetime, it helps foster lively discussions.”

Conversely, for those who did not drink, he would say:

“Sake can make a man reckless, leading him to say things better left unsaid. Best to avoid it.”

Instead, he would offer them rice cakes.

Interestingly, Motonari himself was not particularly fond of alcohol. Yet, he never imposed his personal preferences on others. Rather than measuring others by his own standards, he sought to understand them on their terms. This is an incredibly difficult skill for a person in power to master, yet Motonari made a conscious effort to communicate from his retainers’ perspectives.

Come to think of it, Shimazu Yoshihiro and Mori Motonari share more similarities than one might expect. Still, one can’t help but wonder—if their retainers ever compared notes, wouldn’t they have noticed the inconsistency?

“My lord told me that sake is a great thing.”

“Really? Mine said sake is bad and gave me rice cakes instead.”

Had social media existed in the Sengoku period, managing personal interactions might have been far trickier. Perhaps we should be grateful it did not.

Rule 3: Show favouritism

The third rule is simple and direct:

‘Show favouritism.’

Wait—doesn’t favouritism have negative connotations? Many might think so. But hold on a moment. There’s actually a missing part to this phrase. The full statement is recorded in The Maebashi kyuzo kikigaki (前橋旧蔵聞書):

“One must not act with eko (依怙, bias), but hiiki (贔屓, favouritism) is necessary.”

In this context, hiiki means giving special attention or care to someone. In other words, a leader should take notice of and support their retainers, rather than being indifferent towards them. However, eko—which implies unfair bias—is unacceptable. Showing favour to one side at the expense of others is forbidden.

These words were spoken by none other than Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康), the shogun who established the Tokugawa shogunate, which endured for 15 generations.

Portrait of Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康)

I must confess—there was a time when I misheard this phrase as ‘ego-hiiki (依怙贔屓)’. I thought it meant favouritism driven by ego. Learning that the correct term was ‘eko-hiiki’ felt like being struck by lightning. But when I discovered these words came from Ieyasu, it all made sense.

Ieyasu was known for his strong emphasis on fairness. This is evident in the way he treated the surviving retainers of clans he had defeated. Instead of executing them, he recruited them into his own ranks. The Imagawa (今川), Hojo (北条), and Takeda (武田) clans—all once formidable forces—were ultimately vanquished by Ieyasu. Yet, he recognised the talent and loyalty of the Takeda retainers in particular, incorporating around 900 of them into his army. Among them was Okubo Nagayasu (大久保長安), who later became the Kanayana (金山) magistrate, overseeing the gold and silver mines of Sado Island. While Oda Nobunaga (織田信長) was known for ruthlessly hunting down the remnants of defeated clans, Ieyasu chose to embrace them. This marked a fundamental difference in their approaches to leadership.

How does one perceive their retainers?

Are they mere pawns—interchangeable and disposable? Or are they valued as individuals? A leader’s perspective on this question can determine the strength of their organisation’s unity. The true impact of this choice may only become clear after their passing.

Consider the fate of two unifiers of Japan: the Toyotomi (豊臣) and Tokugawa families. While Toyotomi Hideyoshi (秀吉) failed to establish a lasting dynasty, Ieyasu’s Tokugawa lineage ruled for 15 generations. Interestingly, Hideyoshi and Ieyasu once engaged in a peculiar competition—boasting about their most prized treasures. As a lover of extravagance, Hideyoshi proudly showed off his collection of rare and exquisite tea utensils. He then turned to Ieyasu and asked what treasures he possessed. Ieyasu’s response was unexpected:

“I own no famous tea utensils. My treasures are my retainers—those who would risk their lives without hesitation, plunging into fire or water for me.”

Upon hearing this, Hideyoshi reportedly felt deep shame.

“My retainers are my greatest treasure.”

What a strikingly powerful statement. It’s enough to make anyone’s heart skip a beat. Ah, if only someone would say such words to me one day…

Consider this the ‘Rule 0’. If you forget everything else, remember this.

References

‘sengokujidai no daigosan (戦国時代の大誤解)’, by Kumagai Mitsuaki (熊谷充晃), Saizusha (彩図社), January 2015

‘Sengokubusho no tegami wo yomu (戦国武将の手紙を読む)’, by Owada Tetsuo (小和田哲男), Chuokoron-Shinsha (中央公論新社), November 2010

‘Sengokubusho ni manabu kyukyoku no manejimento (戦国武将に学ぶ究極のマネジメント)’, by Futaki Kenichi (二木謙一), Chuokoron-Shinsha (中央公論新社), February 2019

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/rock/culture-rock/88277/