Imperfect, incomplete, yet beautiful

We often have the idea that something broken or no longer whole is unsatisfactory. Not beautiful. Lacking. Yet, as we will find with two celebrated examples of art, there lies a beauty in imperfection, too. The unexpected allure of the imperfect is embraced in Japanese tea ceremony aesthetics, and we start our exploration with a famous tea bowl.

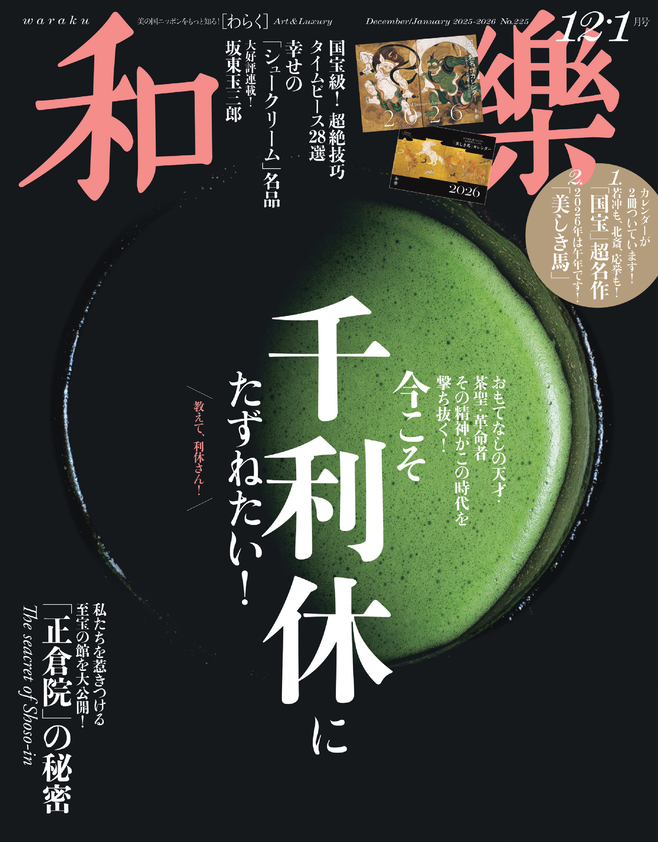

Move the slider to compare images. (Left) “Nike of Samothrace,” Louvre Museum in Paris. (Right) “Bakōhan,” Important Cultural Property, Tokyo National Museum.

Discovering beauty in mended forms

The story of a beautiful tea bowl and its cracks—the celadon glazed tea bowl, known as “Bakōhan,” Important Cultural Property, Southern Song Dynasty (13th century), Tokyo National Museum.

The story of a beautiful tea bowl and its cracks—the celadon glazed tea bowl, known as “Bakōhan,” Important Cultural Property, Southern Song Dynasty (13th century), Tokyo National Museum.

Take a look at the lovely clear color and noble form of this Longquan celadon from Zhejiang Province in China shown above. When in the possession of the 8th Ashikaga shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436-1490), the tea bowl developed some cracks. Seeking a replacement, Yoshimasa sent it back to China.

However, as such a beautiful celadon piece could no longer be made, the bowl was returned to him with metal clamps. These metal attachments helped hold the bowl together. Since the clamps look similar to locusts the tea bowl was named “Bakōhan,” which uses the kanji character for locust. Though losing its claim to beauty in perfection due to the damage, this ceramic bowl has moved on to become a well-known symbol of “beauty beyond perfection.” The metal fasteners if anything, emphasize the delicacy and luminosity of the glassy pottery. Cracks and all, the beauty of this porcelain piece is undeniable.

Even among other celadon porcelain, the “Bakōhan” tea bowl stands out as an exemplary work showcasing the delicately green-tinged glaze desired in Chinese celadon. Notches in the tea bowl’s rim give it the appearance of a six-petaled blossom, and the resulting poetic form is truly elegant. The clamps used to prevent further cracking and hold the fragments together are made of metal. At the time, this method of repair was the standard.

Taira no Shigemori (1138-1179), favorite son of the military leader Taira no Kiyomori, was given this piece by the high-ranking Zen Buddhist priest Busshō. A short while later, the Muromachi shōgun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, came into possession of Bakōhan. Yoshimasa was the leader of Higashiyama culture, which adopted many aesthetics from Zen Buddhism and prized simplicity. A well-known representative of Higashiyama culture is Ginkaku-ji, the Silver Pavillion in Kyoto.

We sense beauty in her form despite the damaged figure

“Nike of Samothrace”—the incomplete goddess who celebrates victory, circa 190 BCE, Parian marble for figure, Rhodian marble for ship (base), 328 cm in height, Louvre Museum in Paris. ©Erich Lessing/PPS

“Nike of Samothrace”—the incomplete goddess who celebrates victory, circa 190 BCE, Parian marble for figure, Rhodian marble for ship (base), 328 cm in height, Louvre Museum in Paris. ©Erich Lessing/PPS

The Greek goddess of victory unfurls her giant wings in the timeless statue, “Nike of Samothrace,” also commonly known as “Winged Victory.” This Hellenistic masterpiece too is also flawed due to its lack of arms and a head. However, the resulting impression is actually incredibly powerful and sublime; it can even be said to enhance the divinity of the goddess. Through this statue, we witness how sometimes something incomplete and imperfect can surpass space and time. Nike has and will forever be celebrated by this beautiful sculpture.

The celebrated sculpture of the goddess Nike who appears in Greek mythology to announce victory. Humans cannot attain perfection though we often seek it. Somehow, we feel hope from the fact that despite the incompleteness of the goddess’s form, she still radiates with beauty and grace. The statue that we see today has undergone some repairs; for instance, due to many missing fragments, the right wing is actually an affixed symmetrical plaster copy of the left wing.

Translated and adapted by Jennifer Myers.