“The Kutani (九谷) artwork is very artistic from the outset. At the same time, a sincere joy erupts from the heart. (It is truly a wonder that Kaga Kutani is so artistic.”

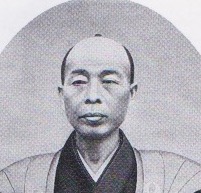

Kitaoji Rosanjin (北大路魯山人), a potter, painter, seal engraver, writer and food connoisseur, once said the following. A man of many talents, he travelled around the world in search of beauty, but he was particularly fond of Kutani ware from Kaga, and the people of this region. He was particularly fond of Kutani ware from Kaga and the people of this region.

Yamashiro Onsen (山代温泉) is a 15-minute bus ride from Kaga Onsen Station, which will be newly opened with the extension of the Hokuriku Shinkansen. While inheriting the history of a long-established ryokan that has welcomed many cultural figures to the area since the Edo period, Kai Kaga (界 加賀) is gaining popularity as a fresh take on hot spring ryokans.

The onsen ryokan, where Rosanjin also liked to stay, has now launched yet another new initiative. What has opened is the ‘Kintsugi Kobo (金継ぎ工房)’. We covered the thoughts behind this initiative, the first of its kind in Japan for a ryokan, and the experiences that can only be had at Kai Kaga.

Unique presence in Hokuriku’s spa towns

Kai Kaga is an onsen ryokan that has taken over the history of the long-established Shiroganeya (白銀屋) ryokan in Yamashiro Onsen, Kaga. The traditional building, including the reception hall, was built in the Bunsei era during the Shiroganeya era, which was founded in 1624. Bengara Koshi (紅殻格子: The reddish-brown latticework) on the front of the building is a traditional architectural style from the Kaga region, where thin timbers are combined vertically and horizontally and painted with a reddish-brown pigment called bengara.

Kai Kaga is an onsen ryokan that has taken over the history of the long-established Shiroganeya (白銀屋) ryokan in Yamashiro Onsen, Kaga. The traditional building, including the reception hall, was built in the Bunsei era during the Shiroganeya era, which was founded in 1624. Bengara Koshi (紅殻格子: The reddish-brown latticework) on the front of the building is a traditional architectural style from the Kaga region, where thin timbers are combined vertically and horizontally and painted with a reddish-brown pigment called bengara.

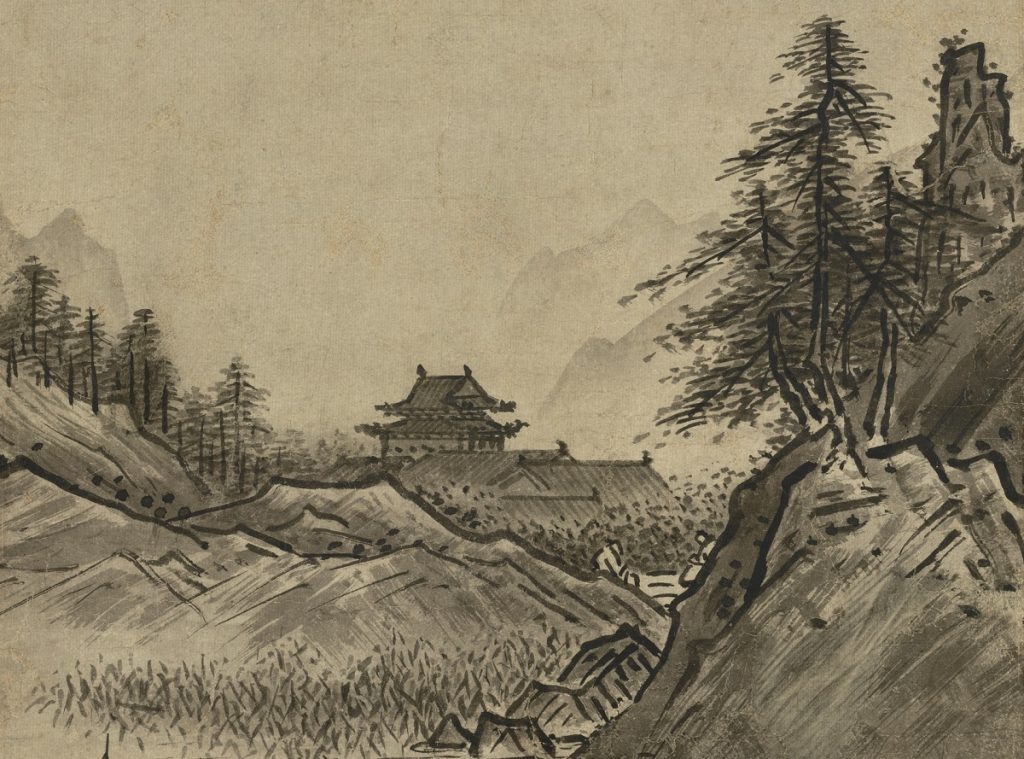

In the Edo period, it was common for a hot spring resort to be centred around a communal bathhouse, with the town surrounding it. In the Kaga region, inns lined up around the public baths, known as ‘so-yu (総湯)’. Yamashiro Onsen is said to have been discovered by the monk Gyoki (行基) when he travelled through the area some 1,300 years ago, and the surrounding townscape around the so-yu has long been known as the ‘yuno-gawa (湯の曲輪)’.

The iron ring (top photo), to which the reins were tied during the Edo period when people came here on horseback, is still in place at the foot of Bengara Koshi, allowing visitors to imagine what the atmosphere would have been like during this time.

In the restoration work carried out in 2014-15, Yamamoto Nobuyuki (山本信幸) of Shajiken (社寺建), a specialist in the restoration of cultural properties such as the Kabuki-za (歌舞伎座), took the lead in removing the pillars and beams one by one, carefully repainting them and reassembling them.

Take, for example, the ‘Waku no uchi (枠の内)’ of the front hall. To withstand the winter snows, the thick daikoku-bashira (大黒柱: main pillar) and large log beams were assembled without any metalwork. This style was once common in the Hokuriku region, but is difficult to reproduce today using the same materials, making it a valuable architectural feature.

The eight-storey guest room building built behind the traditional building has been designed to match its surroundings, with its magnificent udatsu (卯建/宇立: latticework), roof tiles and century-old red pine trees, as well as the Bengara Koshi of the traditional building. The building is located in the centre of the city. The contrast between the Bengara Koshi and the modern architecture in the evening light creates a unique presence in a traditional hot spring resort.

“The tableware is the clothes of the dish”

“The existence of tableware in relation to cooking is like the existence of clothing for human beings. Just as a person cannot live without clothing, a dish cannot stand on its own without crockery. In other words, tableware is the kimono of cooking.”

Kitaoji Rosanjin is said to have said this at a banquet. He first came into contact with ceramics in Kaga in 1914, when he was still an unknown artist. The young man, who called himself Fukuda Taikan (福田大観), was taught to make pottery by Suda Seika (初代須田菁華), the founder of the famous revived Kutani pottery kiln in Yamashiro Onsen.

Rosanjin, who came to know deeply the charms of Ko-Kutani (古九谷) and the revived Kutani ware, praised Ko-Kutani, which, as he said at the beginning of this article, was “very artistic” and “masculine, dynamic and elegant, and is by far superior to all other pottery in the world”. He is said to have entertained guests with Kutani plates and other ceramics made by himself.

One of the great attractions of Kai Kaga is that you can not only enjoy the seasonal flavours of the Hokuriku region, but also enjoy them with Kutani ware dishes, which were also loved by Rosanjin. Seasonal and local delicacies such as Kutani ware,, abalone and snow crab are laid out in front of you, dressed in the ‘clothing’ that brings out the best in them.

The special kaiseki (traditional multi-course japanese dinner) of the day featured ‘Katadofu no Konbu jime (堅豆腐の昆布茶〆め)’ as a starter (see photo above), served on a small plate with ‘kinjiso miso (金時草味噌)’. This appetiser, served on a small Kutani ware plate with ‘Amaebi Kojizuke (甘海老麹漬け: pickled sweet prawns in malted rice)’ and lotus root, is a menu item called ‘Gotochi Sekizuke (ご当地先付け)’, a ‘Kai’ original, where you can enjoy unexpected combinations and new cooking methods, while sticking to ingredients and cooking methods unique to the region.

Katadofu (堅豆腐) is traditionally made at the foot of Mount Hakusan (白山) in Kaga, one of Japan’s three most famous mountains, using a large amount of bittern and firming it with a large weight. It is characterised by its firmness, which is said to be ‘so firm you could bind it with a rope’, and has long been eaten in a dengaku style. The sweet, gentle flavour of miso made with seasonal kintoki grass, a Kaga vegetable, and the pleasant crunchiness of katadofu add a new dimension to this traditional Kaga taste.

The colourful ingredients in the bowls of simmered dishes such as ‘Awabi sinjyo (鮑真薯)’ and ‘Aigamorosu no Orengi Sumiso kake (合鴨ロースのオレンジ酢味噌かけ)’ are pleasing to the eye (see photo above). ’’Uchiki Akagawa Amaguri Kabocha’ tempura, futa-mono (dishes served in lidded pottery) , dainomono (dishes served on a stand), followed by blackthroat seaperch with clay pot rice as the main course.

Blackthroat seaperch, also called akamutsu, is one of the most expensive fish, known as ‘the kinki of the east and the Blackthroat seaperch of the west’. It is fatty regardless of the season and is also known as ‘whitefish toro’. The rice is cooked slowly in an earthenware pan and is slightly soaked in the fat from the Blackthroat seaperch and the flavour of the fish seems to melt gently onto the tongue.

At Kai Kaga, they commissioned young Kutani ware artists to create dishes that best complement each individual dish.

Human nature is not affected by the clothes we wear. But it can certainly enhance their attractiveness many times over. The seasonal and local flavours served at Kai Kaga were made even more vivid and striking by the young contemporary Kutani artists.

The history packed in the vessels will also be passed on.

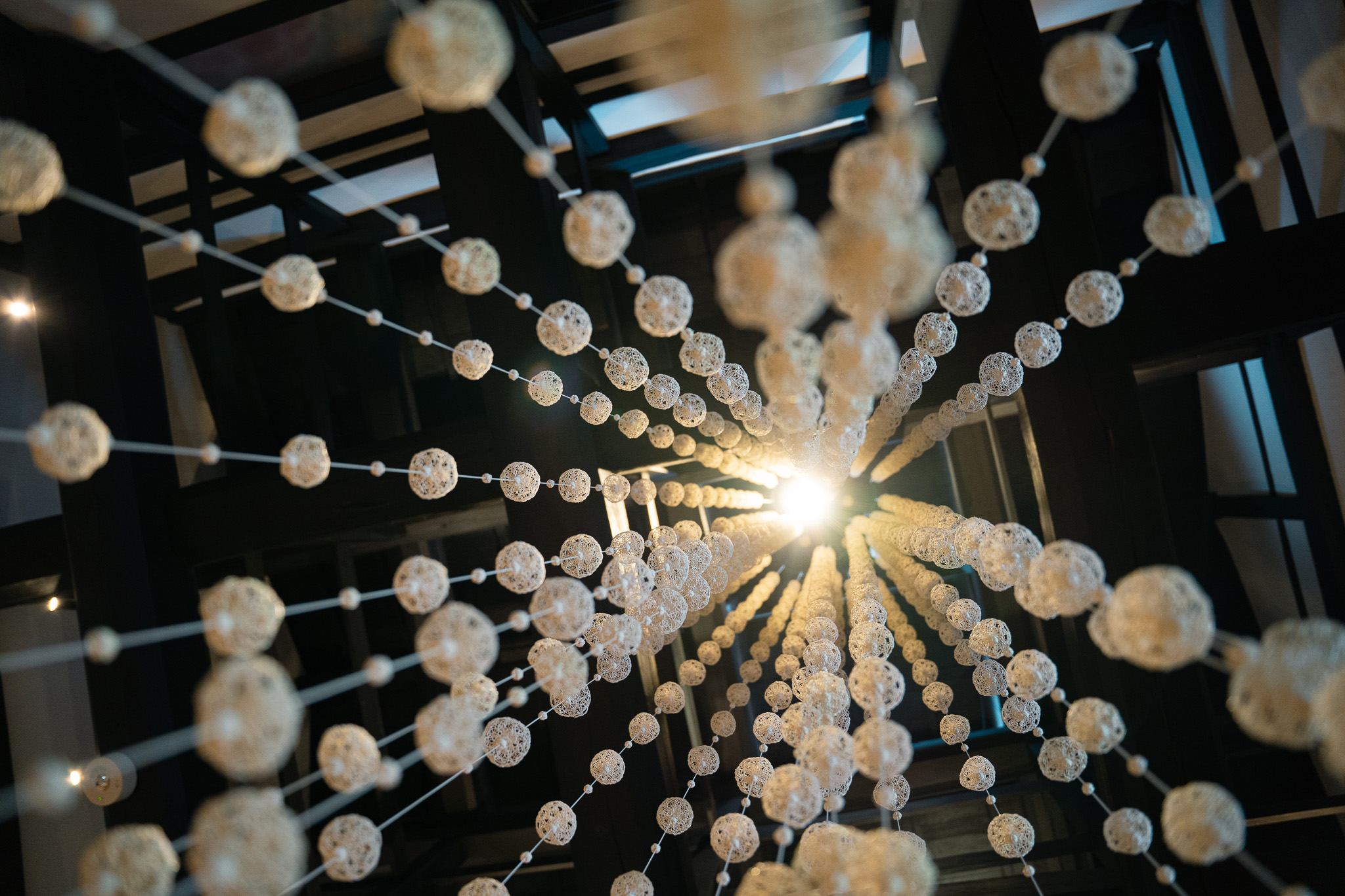

Kintsugi (金継ぎ) was a culture that spread with the rise of the tea ceremony in the Muromachi period. Rather than covering up the broken marks, they decorated them with gold and silver powder and enjoyed them as the scenery of the vessel. The spirit of wabi-cha (わび茶), which sees beauty in imperfect and dying things, had a great influence on the Japanese sense of beauty later on.

“At Kai Kaga, we use a lot of tableware every day to serve our guests’ meals, but no matter how careful we are, there is always a chance that it will chip or break when bumped or dropped during clean-up or washing. The kintsugi workshop was started at the initiative of the staff, who wanted to preserve the Kutani tableware as part of its charm, rather than throwing it away.”

Sudo Reina, general manager, says this about the new kintsugi Kobo (photo above) that opened on the premises of Kai Kaga in April 2023. It is the first time in Japan that a dedicated kintsugi facility has been created inside a hot-spring inn. The staff have received direct guidance from lacquer artist and kintsugi expert Nakaoka Yoko, and now do most of the restoration work on the tableware they use themselves. (Every day from 15:30 to 16:00 for 30 minutes, with a maximum capacity of six people).

“The process of kintsugi involves more than ten steps, but guests can also experience the process of filling in cracks and chips with sabi-urushi (さび漆), a mixture of ki-urushi(生漆) and Tonoko (砥の粉: polishing powder), and the final decorative process of sprinkling gold powder and other materials on the surface”. Noguchi Hina, a staff member who is usually in charge of customer service, explains the kintsugi techniques she has learnt.

At Kai Kaga, where nearly half of all staff members are now trained in basic kintsugi techniques, actually restored small plates, small bowls and large plates are displayed in a corner of the workshop set up in a renovated part of the traditional building, and are also used in the tableware used daily.

Noguchi-san, who carefully explained each step of the process, explains the appeal of kintsugi, saying, “It seems to me that we are connecting not only the broken plates but also the memories and history of their owners that are packed in those plates”.

If humans cannot do without kimonos and food cannot do without tableware, what is essential to ‘tradition’?

Rosanjin once said of art, including ceramics: “As long as human beings create, human beings are needed. Before making ceramics, we must first make people”. As it is people who carry on the culture and people who receive what is passed on, what is necessary for tradition is the presence of people involved.

Perhaps this does not only refer to potters and kintsugi craftsmen. It should also include the staff who take good care of the dishes, the chefs who beautifully serve seasonal ingredients on the kintsugi dishes, the people who enjoy the food served on the dishes, the people who love the onsen ryokan, and the people of the town.

That is why tradition is still alive in Kaga. The reason why Rosanjin, who had difficulty getting to know people because of his individuality, maintained close contact with the people of Kaga throughout his life is probably because the way of life in which people feel close to culture and try to live with beauty has lived on for a long time in this region.

(Text and photos by Tomoro Ando)

Photo gallery

Kai Kaga Access

922-0242

18-47, Yamashiro Onsen, Kaga, Ishikawa, Japan (map)

Official website:https://hoshinoresorts.com/ja/hotels/kaikaga/

References

Kitaoji Rosanjin, Rosanjin tosetsu (Chuko Bunko, 1992)

Nihon no Shoko Seikasyu Zenshu Ishikawa Editorial Committee (ed.), Kikisho Ishikawa no Syokuji) (Nosan Gyoson Bunka Kyokai, 1988)

Kiyokawa Hiroki, Kintsugi no Bi to Kokoro (Tankosha, 2021)

Kaga no Bi: 180-nen no Toki wo Koete ko-kutani Roman Karei naru Yoshidaya Ten (Asahi Shimbun-sya, 2005)

Zusetsu, Botugo 50 nen Kitaoji Rosanjin ten (EMI Network, 2009)

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/travel/223053/