Texts by Sawada Toko

Dressing up and adorning oneself with sparkling jewellery. There lies the human desire to be beautiful and to add colour to one’s life. In our series ‘Bisso (美装) no Nippon: The History of dressing up’, writer Sawada Toko traces the history of various ornaments and jewellery, and explores the mysteries behind the act of dressing up.

Mystery of the doctor who somehow found out it was coral

This was the era of the historical drama ‘Dousuru Ieyasu (どうする家康)’ – that is, the first half of the 17th century. In Kyoto, there was a doctor named Yoshida Sojun (吉田宗恂). After serving Toyotomi Hidetsugu (豊臣秀次) and Emperor Goyozei (後陽成天皇), he moved to Edo, where the shogunate had just been established, and became Tokugawa Ieyasu’s personal physician.

One day, a ship from overseas brought branches of coral. Coral trees, especially the beautiful coral called ‘ Hoseki sango (宝石サンゴ jewel coral),’ can be found in the seas around Japan, but they are inaccessible to humans at a depth of at least 100 meters. For this reason, the harvesting of jewel coral had not yet begun in Japan at that time, and no one around Ieyasu knew what this item was. Only Yoshida Sojun, however, was able to identify it, and he gave a detailed explanation of its place of origin and other details.

Today, we, who have been exposed to many TV programs and illustrated books since we were small children, can immediately imagine a coral tree with beautiful branches when we hear the word ‘ sango (coral)’. However, Tokugawa Ieyasu and his contemporaries, who had no way to obtain coral from the deep sea, had no idea what coral was when they saw it.

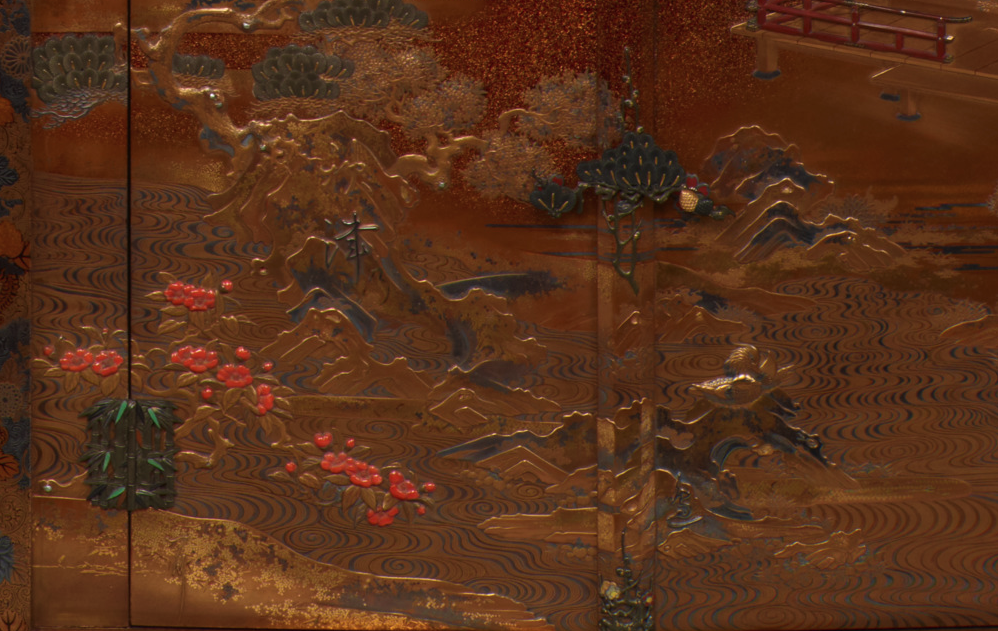

However, this does not mean that Ieyasu and his contemporaries were unaware of coral. In fact, coral was a familiar name not only to Ieyasu, but also to the people of the Nara and Heian periods. This is because Buddhist scriptures often refer to coral as gold, silver, lapis lazuli, hari (玻璃, another name for glass), shako (硨磲, giant clam) and meno (瑪瑙、agate), and collectively they are known as the ‘seven treasures’.

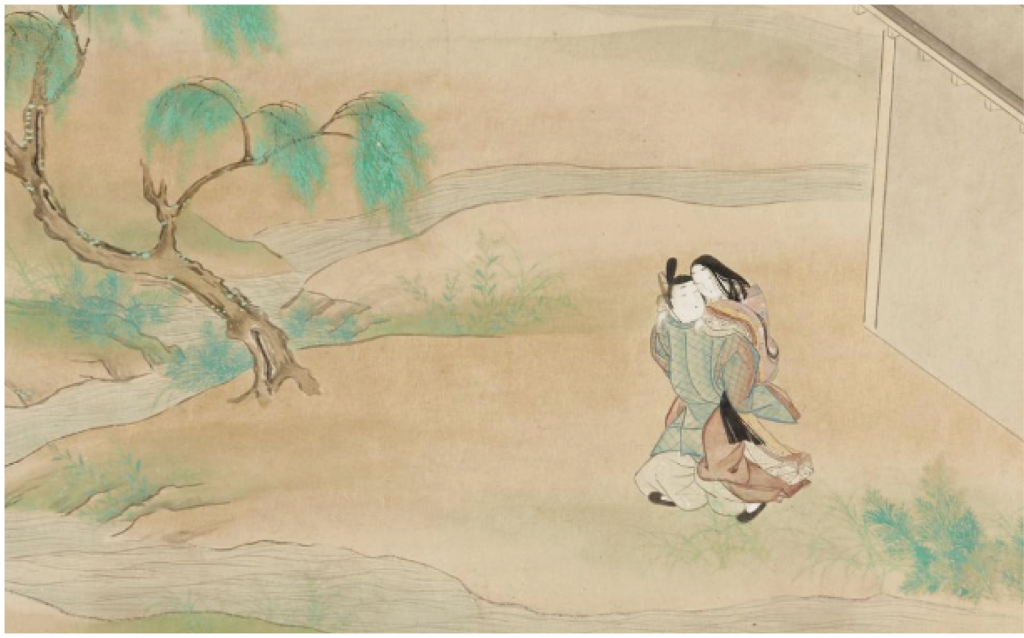

For example, in the historical tale ‘Eiga Monogatari (栄花物語)’ written in the mid to late Heian period, there is an episode in which Fujiwara no Michinaga (藤原道長), who had three daughters as empresses and became the grandfather of two emperors, held Bantoe (万灯会, a Buddhist lantern festival) at Hōjōji (法成寺) Temple, which he himself had requested. The story also tells that a beautiful tree decorated with the seven treasures was erected around the pond, and that a net made of gold and silver was decorated to light the tree. Some elements of it are fictionary, so it is necessary to take this into account when reading it, but it is a spectacular scene.

Traveling from the Mediterranean to the Shosoin

In the Shosoin (正倉院) Repository, which housed the relics of Emperor Shomu (聖武) during the Nara period, coral beads were used to decorate the crown of the Great Buddha statue at Todaiji Temple during the opening ceremony of the statue in 752. They were processed into beads together with lapis lazuli and pearls, and used as hanging ornaments called suishoku (垂飾). The size of the largest corals is about one centimeter in length, which is very small in the modern sense of the word.

As mentioned above, corals cannot be collected in the seas around Japan unless they are found at considerable depths. In contrast, in the Mediterranean Sea, jewel coral called saffron coral lives at depths of around 30 meters, which is deep enough for humans to dive without breathing, depending on their training. Plinius, a naturalist who lived in ancient Rome, devoted many pages in his book ‘Naturalis historia (博物誌)’ to the ecology and uses of coral, as well as how it was prized in various regions. According to Plinius, coral was highly prized by the Indians, and it appears that coral was transported not only to India but also to the rest of the world through trade routes.

The coral beads in Shosoin were probably brought from the distant Mediterranean Sea, and their value was far more precious than today’s coral. The small corals in the Shosoin storehouse have traveled a long journey, that describing it as a mere centimeter does not do it justice.

Incidentally, Shosoin also has a 27-centimeter-tall coral log in its collection. However, according to Professor Suzuki Katsumi (鈴木克美) of Tokai University, who investigated this coral in 2002, it is indeed biologically a coral, but it belongs to a different family than jewelry corals (Shosoin Bulletin, 24, ‘Report on Shosoin Coral Research,’ Shosoin Coral Museum). Since the colour is different from that of jewelry coral, it is difficult to associate it with coral. It is an item of great mystery.

People’s Gaze Changing with the Times

By the way, when we encounter such underwater fictions as ‘Ningyo hime (人魚姫, The Little Mermaid)’ and ‘Urashima Taro (浦島太郎),’ we always imagine a scene with beautiful corals growing in the sea. The story of Urashima Taro can be found as far back as the ‘Nihon Shoki (日本書紀, Chronicles of Japan), a history book compiled in the early Nara period, but the word ‘ 珊瑚 (coral)’ actually already appears in the ‘Urashima ko no Den (浦島子伝)’ written in the early Heian period. The coral here does not appear in the form of a tree, as we recall, but rather as a decorative item in the home of a nymph at the bottom of the sea, along with various types of jewelry. This is an expression of the ancient people who accepted coral as a small jewel.

On the other hand, it is interesting to note that the Engishiki (延喜式),’ a collection of laws and ordinances compiled in the early Heian period, already seems to have understood the shape of the coral tree. In the Engishiki, an entry for the Jibusyo (治部省, Ministry of civil administration), which lists items that were considered auspicious at the time, there is an explanation of an item called ‘shibakusa (芝草),’ which is a type of sacred plant. It is said to have been prized as a medicine for longevity because it retains the same shape for several years. However, the ancient Chinese treatise ‘ Ronko (論衡, Lunheng)’ describes it as a plant with three leaves and bean-like seedlings, and it is assumed that this is the same grass-like plant that has been excavated in tombstones and other grave markers from various locations.

And interestingly, the Engishiki describes this grass,

‘ Katachi ha sango ni nitari. Siyo renketu. (…) Ichinen ni sanka ari. (形は珊瑚に似たり。枝葉、連結。(中略)一年に三華あり。)

Meaning: The shape resembles coral, the branches and leaves are interconnected, and it flowers three times a year.

The shape of the shibakusa described in the Engishiki is more reminiscent of that of a grass than of a mushroom, as can be inferred from the fact that the shibakusa has a series of branches and leaves. And it certainly resembles the coral tree as we know it, but then how did the writer of this text know the shape of the coral tree itself, rather than the coral beads? It makes me wonder if there might have been corals that came to Japan in the form of branches since that time.

Although a little later in time, the ‘Hogen Monogatari (保元物語),’ a military tale about the Hogen Rebellion of 1156, is a tale that describes the death of Emperor Toba (鳥羽法皇) and the grief of his wife, Bifukumonin (美福門院),

‘Hekigyoku no yuka no ue niwa, furuki Ofusuma munasiku nokori, sango no makura no sita niwa, mukashi wo kouru onnamida nomi itazurani tumoreri (碧玉の床の上には、旧き御衾空しく残り、珊瑚の枕の下には、昔を恋ふる御涙のみ徒らに積れり)

Meaning: On the jasper floor, the old bedclothes (ofusuma, meaning bedclothes) remain empty and under the coral pillow, only tears of longing for the old days are piled up.

The coral decoration is described in the following way.

The contrast between the green jade and the bright red coral is terribly beautiful, and is a haunting description that highlights the absence of the deceased. In fact, however, similar descriptions of the deceased can be found in the ‘Tyoyagunsai (朝野群載)’ and ‘Honchomonsui (本朝文粋),’ a collection of Chinese literature compiled during the Heian period, so it seems that this was considered a standard phrase at the time.

Today, when we are inundated with a variety of colors, the vermilion of coral is nothing new to us. However, in ancient times when only natural colors existed, the vivid vermilion of coral, which came only from overseas, must have been considered more precious than gold or silver.

The way we look at one thing changes dramatically with the passage of time. The history of coral is also the history of our own values.

Sawada Toko

Born 1977, Kyoto. Graduated from Doshisha University, Faculty of Literature, and completed the Master’s course at the same university. She made her debut in 2010 with ‘Koyo no Ten(孤鷹の天)’, which won the Nakayama Yoshihide Literature Award(中山義秀文学賞); won the Shinran Prize(親鸞賞) in 2016 for ‘Jakuchu(若冲)’ and the 165th Naoki Prize in 2021 for ‘Hoshi Ochite, Nao(星落ちて、なお)’.

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/227788/