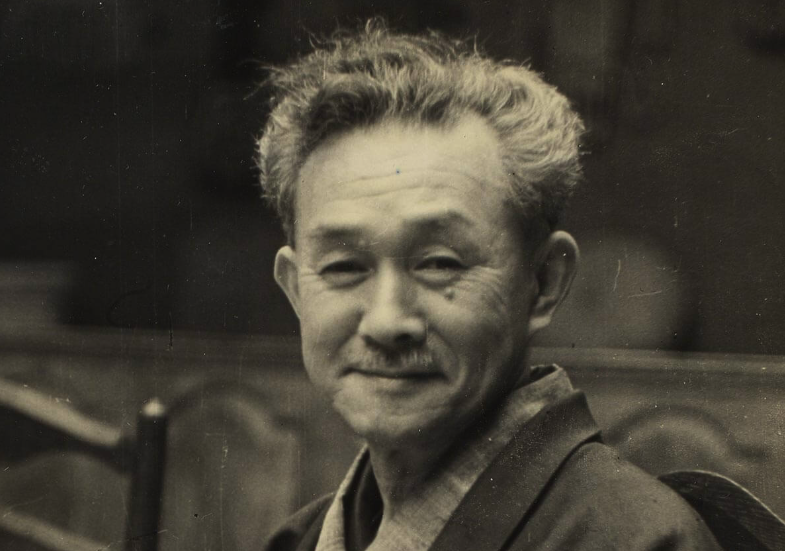

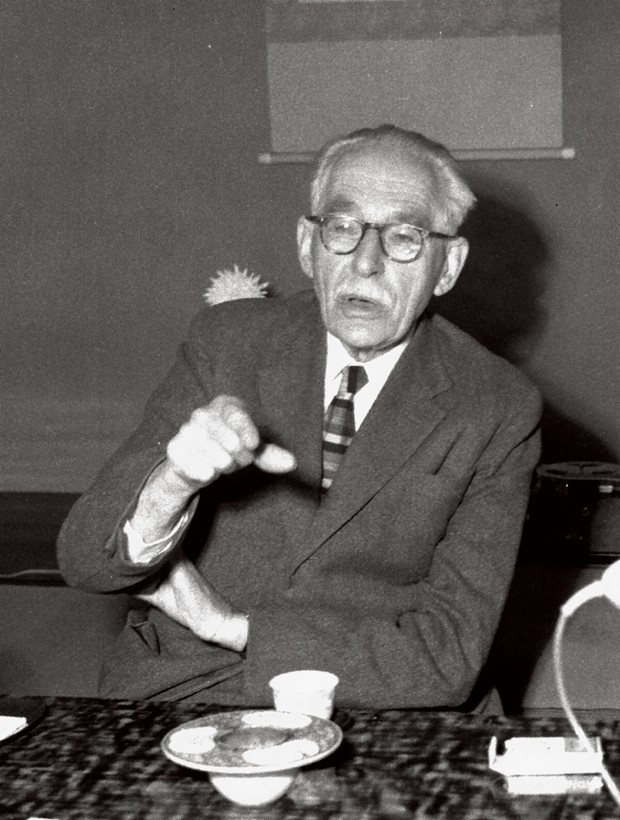

Yanagi Muneyoshi, father of mingei

Mingei (民藝, folk art) is widely appreciated for its simplicity and beauty, and is often referred to as the ‘Yo no bi (用の美, Beauty of everyday objects)’. Mingei is a new aesthetic that emerged at the end of the Taisho era, although it is now well-known. The term ‘mingei’, short for popular crafts (民衆的工芸), was coined by Yanagi Muneyoshi (柳宗悦), who shared the same perception of beauty as the ceramicists Hamada Shoji (濱田庄司) and Kawai Kanjiro (河井寬次郎), amongst others. Here we introduce four of these folk art legends.

If it weren’t for this man ‘Yo no bi’, which enriches our lives, would not have been created!

Yanagi Muneyoshi, father of mingei

First, let’s look briefly back at the footsteps of Yanagi Muneyoshi, known as the ‘father of mingei’.

Born in Azabu (麻布), Tokyo, in 1889 (Meiji 22), Yanagi published the literary magazine ‘Shirakaba (白樺)’ when he was a student at Gakushuin (学習院) High School, together with Mushanokoji Saneatsu (武者小路実篤) and Shiga Naoya (志賀直哉), who later became renowned as great writers. Shirakaba not only published novels, but also actively took up Western art, and Yanagi played a central role in this.

After graduating from the Philosophy Department of Tokyo Imperial University, Yanagi went on to become a religious scholar. At the time, Yanagi was greatly influenced by the English religious poet and painter William Blake, whose ideas emphasised the importance of one’s own intuition, and he developed his own ideas based on art and religion.

Around this time, Yanagi’s life took a major turn when a young man from Korea visited him. Seeing a small Yi dynasty blue-and-white pot as a souvenir, he discovered a whole new kind of beauty. His interest in Korean folk ceramics led him to the Korean peninsula, where he was impressed by the wide variety of crafts available.

Furthermore, Yanagi was attracted to Buddhist statues created by Mokujiki (木喰), a monk who travelled around the country during the Edo period, and during his travels around Japan, he learnt about the many crafts with a rich regional flavour and unique craft cultures. He met Hamada and Kawai at the time, and through discussions with them about beauty, he came to formulate the idea of mingei that true beauty is to be found in things created unintentionally by ordinary people.

The characteristics of mingei are described by Yanagi in terms of ‘practicality, unmarkedness, plurality, affordability, locality, specialisation, tradition and otherness’. Yanagi’s search for beauty led him to the folk art movement, which he not only researched and critiqued, but also put into practice by visiting handicrafts throughout the country and using them in all aspects of life. He built the ‘Nihon Mingeikan (日本民藝館)’ in Komaba (駒場), Tokyo, to display his collection of folk crafts and to pass on his achievements.

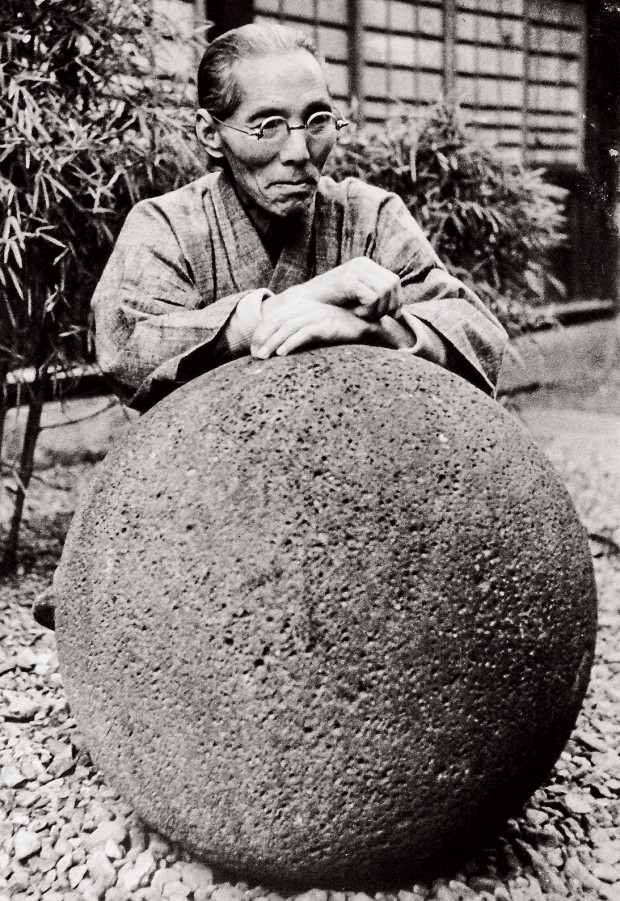

A lifetime of pursuing his own unique form as a potter, after encountering Mingei

Kawai Kanjiro

Kawai Kanjiro, who had wanted to become a ceramic artist since junior high school, went to the Ceramics Department of the Tokyo Higher Technical School (now Tokyo Institute of Technology) in Yasuki (安来), Shimane Prefecture. Two years below him was Hamada Shoji, who joined the Kyoto Municipal Ceramics Laboratory as an engineer after graduation, where they worked together on glaze research as colleagues.

Kawai eventually set up a studio and residence, Shokei yo (鐘溪窯), on the Gojozaka (五条坂) in Kyoto, and at his first solo exhibition presented works that made full use of old oriental ceramic techniques, which were well received for their skill and perfection. However, Kawai himself gradually began to have doubts about his own ceramics, and it is said that the harsh criticism he received from Yanagi Muneyoshi around the same time also added to his doubts.

Later, when Kawai saw the ceramics called slipware that Hamada brought back from England, he found his true nature in everyday objects and his doubts were put to rest. When he met Yanagi through Hamada, they came to understand each other beyond any hard feelings from the past and became absorbed in the mingei movement.

Kawai’s style changed dramatically as he moved away from the popular style of old Chinese ceramics to incorporate a wealth of Japanese folk pottery motifs. With an awareness of the ‘Yo no bi’, Kawai produced numerous objects that blended in with everyday life.

His pottery production was interrupted during the Second World War, but when it resumed after the war, he produced a series of ambitious works, as if to release his pent-up energy. He produced powerful pieces full of life and mysterious forms, expanding his style beyond the boundaries of mingei into a new kind of beauty.

His artistry was highly regarded both at home and abroad, and he was nominated for the Order of Cultural Merit and Living National Treasure, but he declined all offers. Kawai was not interested in awards and honours until the end of his life, and he engaged with pottery as a potter.

Kawai Kanjiro’s works are somewhat modern and original!

Top right: ‘Shinsha tsutsugaki henko (辰砂筒描角筥)’, 1950, with red glaze, which Kawai loved, bottom right: ‘Shiroji maru mon sumikiri bachi (白地丸文隅切鉢)’, 1939, top left: ‘Sanshiki uchigusuri chawan (三色打薬茶碗)’, 1963, representing the energetic style of the post-war period, bottom left: ‘Neriagede uzura monkaku bachi (練上手鶉文角鉢)’, 1934, made by layering three types of clay (all photographs from the Japan mingei museum)

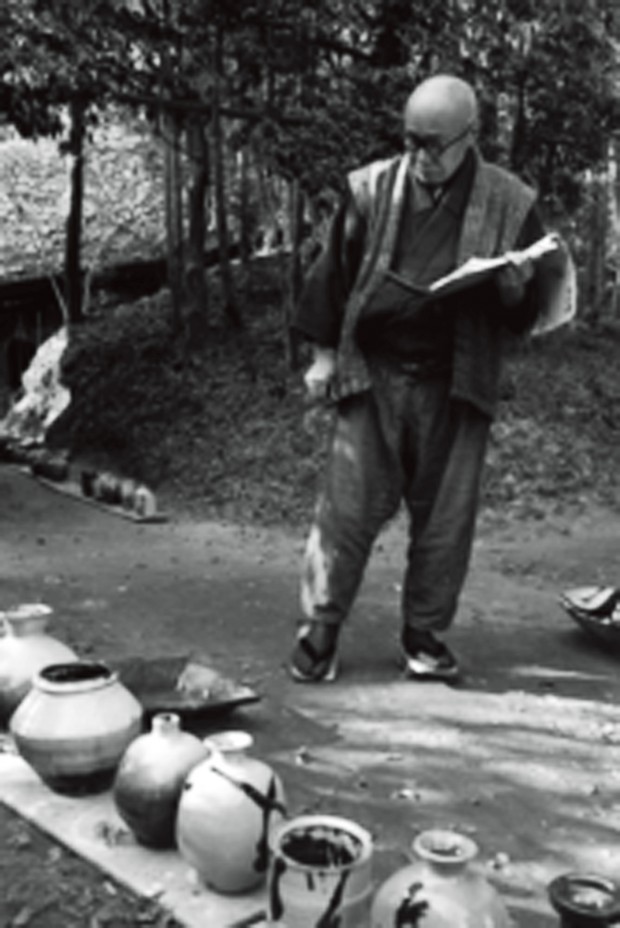

English-trained potter who supported the mingei movement as the right-hand man of Yanagi Muneyoshi

Hamada Shoji

Hamada Shoji, who together with Yanagi Muneyoshi and Kawai Kanjiro promoted the mingei movement from its early days, is one of Japan’s leading modern and contemporary ceramic artists.

As he recalls, ‘I found my way in Kyoto, started in England, studied in Okinawa and grew up in Mashiko (益子)’, Hamada’s life as a potter cannot be described without mentioning these four places.

After entering the Ceramics Department of the Tokyo Higher Technical School, Hamada made a lifelong friend in Kawai Kanjiro, a senior student, and after graduation he joined the Kyoto Municipal Ceramics Laboratory, as did Kawai.

Around this time, he met the English potter Bernard Leach at a solo exhibition and visited him at the home of Yanagi Muneyoshi in Abiko (我孫子), Chiba Prefecture, where he also became friends with Yanagi, and in 1920 (Taisho 9) he travelled to England with Leach. During the three and a half years he spent with Leach in St Ives, Hamada learnt to use local materials and to make use of tradition in his life and work.

After returning to Japan, Hamada went straight to the Kawai residence in Kyoto and stayed there. He brought Yanagi and Kawai together, and the three of them took the lead in promoting the mingei movement.

Hamada’s pottery production in Japan began in Tsuboya (壺屋), Okinawa and Mashiko (益子), Tochigi. In Okinawa, Hamada stayed for an extended period of time, practising the pottery methods he had learnt in England and leaving behind works in the style of traditional Tsuboya ware. In Mashiko, where he moved in search of a place for production rooted in daily life, he moved into a number of old houses and immersed himself in pottery making. He pursued a style of simple forms made almost exclusively on the hand wheel, and bold patterns created by the flowing glaze.

After Yanagi’s death, Hamada became the second director of the ‘Japan mingei museum’. It is no exaggeration to say that he devoted his entire life to mingei.

Hamada Shoji’s solid and powerful vessels reflect a ceramic consciousness rooted in daily life

All of them are characterized by a strong and healthy style, using the clay and glazes of Mashiko, where the pottery was based. Top right: ‘Kakigusuri aonagashi gaki kakubachi (柿釉青流描角鉢)’, 1954; bottom right: ‘Shirogusuri kuronagashi gaki hachi (白釉黒流描鉢)’, 1960s; top left: ‘Aishiogusuri kushime hachi (藍塩釉櫛目鉢)’, 1958; bottom left: ‘Shirogusuri tetsuemarumon tsubo (白釉鉄絵丸文壺)’, 1943 (all photographs from the Japan mingei museum)

British potter who linked Japan and the West and introduced the mingei movement abroad

Bernard Leach

Bernard Leach, an englishman who was not only a potter but also a bridge builder in various aspects of the mingei movement, is an indispensable figure in the development of Japanese mingei.

Born in Hong Kong and separated from his mother shortly after birth, Leach had lived with his grandfather in Japan. When he moved to England and attended the London School of Art, he became acquainted with the poet and sculptor Takamura Kotaro (高村光太郎) and read a book by Koizumi Yakumo (小泉八雲), which led to a strong admiration for Japan.

In 1909, at the age of 22, Leach finally arrived in Japan. He developed contacts with colleagues of the literary magazine Shirakaba, and became lifelong friends with Yanagi Muneyoshi, who attended an etching class held by Leach, with whom he discussed William Blake and ceramics, and who influenced and stimulated each other ideologically in relation to art.

Leach also became interested in Raku ware (樂焼) and was introduced to Ogata Kenzan VI (六世尾形乾山). In 1917 (Taisho 6), he built a kiln in the Yanagi residence in Abiko, Chiba Prefecture, and began his career as a ceramic artist.

After a stay in Japan of about ten years, Leach returned to Japan accompanied by Hamada Shoji. He built a Japanese-style climbing kiln in St Ives on the Cornwall peninsula in south-west England and established the Leach Studio. He played a major role as the founder of modern British ceramics and as an ambassador for the spread of the ideas of the mingei movement abroad.

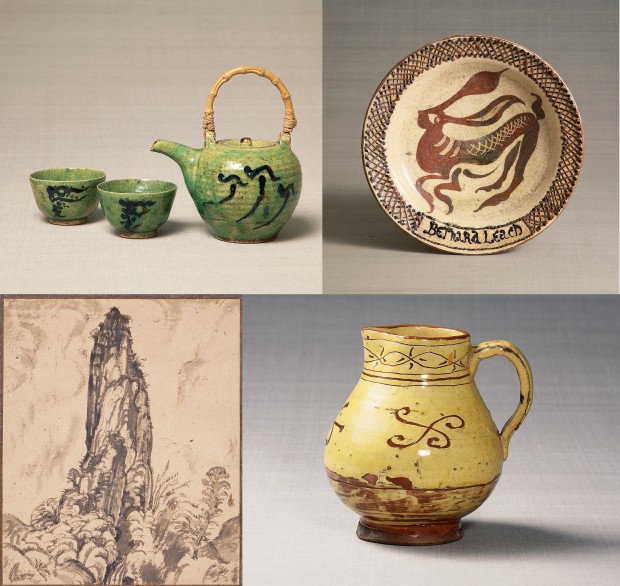

Leach’s style is characterised by a fusion of slipware, a traditional technique of western ceramics, and oriental ceramic techniques. His etchings and drawings of familiar figures and travel scenes also survive.

The perfect harmony between British taste and Japanese mingei shines through!

Top right: ‘Rakuyaki usagimon sara (楽焼莵文皿)’, 1919, with an impressive, lively rabbit, bottom right: ‘Garena yusembori suichu (ガレナ釉線彫水注)’, 1922, made at the Leach Studio, top left: ‘rakuyaki ryokuyu tsutsugaki chaki (楽焼緑釉筒描茶器)’, 1919, bottom left: ‘Iwazu (Karuizawa) (岩図(軽井沢))’, 1919, etched work (all photos: ‘Japan mingei museum’).

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/rock/craft-rock/1054/