Your first step to enjoying suibokuga

When you write with a pencil or a ballpoint pen, you apply a consistent pressure and your hand moves over the paper, leaving behind a fine, uniform line. By contrast, when you use a brush and ink on washi (和紙) paper, you can create lines that are rich in variation.

Take your mind back to a time where you might have experienced trying Japanese calligraphy. Try to recall the feeling of holding the brush, dipping it in the ink, and drawing it across the washi paper.

As the ink soaks into the soft bristles of the brush, it feels a little heavier. When you place the ink-filled brush onto the paper, it feels soft and sinks in slightly, and the ink soaks in almost instantly.

As you move the brush, it leaves a clear black line, and the ink also spreads a little around the edges. If you use just the tip of the brush and move it quickly, you get a fine line. If you hold the brush at an angle and move it slowly, you get a thick line. When you first start drawing, the brush is full of ink, so it smudges easily, but as you continue, the lines gradually become faint and dry. You can also create a variety of different lines by pressing the brush lightly onto the paper, flicking it vigorously, or gradually lifting it to make the line thinner.

This is a sensation that you can only get with a brush and ink, not with a pencil. Ink painting is a unique East Asian art form that has freely and boldly developed the expression of lines through these varied brush movements, as well as the effects of blurring and fading ink

Having an understanding of this feeling of moving the brush is a key to appreciating ink paintings.

Let’s start by appreciating a famous piece

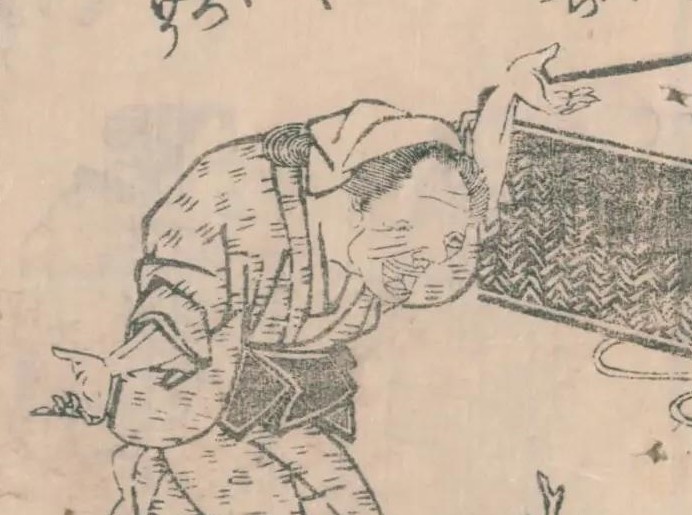

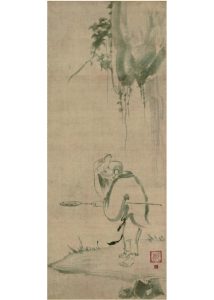

Let’s take a closer look at a masterpiece of early Japanese ink painting, the kensu-osho-zu (蜆子和尚図).

The red seal in the bottom right corner suggests the artist is Kao Ningha (可翁仁賀). He’s believed to have been a Zen monk active in the early 14th century, but his exact biography is unknown.

What do you see in this painting?

An old man holds a net in his left hand and is picking up a shrimp with his right fingers. He has a slight smile, looking happy and contented. This old man is the legendary Zen priest Kensu-osho (蜆子和尚), who lived in late Tang dynasty China around the 9th century. He’s said to have lived a life of a vagabond, always wearing the same clothes and catching clams and shrimp by the river to eat. His simple and free way of life was thought to contain the truth and enlightenment of Zen Buddhism.

While reading into the scene and its story, don’t you get a lot of other information from this painting, too? This is where we can see the variety of lines we just talked about.

First, the face and limbs are clearly drawn with thin, dark lines. However, the lines aren’t uniform; they get a little thicker, darker, and sometimes break off. The artist must have used a fine brush, gliding the tip over the paper rhythmically.

On the other hand, the robe is drawn with light ink, using a thick brush held at a slight angle and moved quickly. If you look at the lines closely, you can feel how the brush was pressed lightly onto the paper, lifted slightly, and then swept away with a flourish.

This suibokuga is woven from these diverse lines. Through them, we can appreciate the vibrant expression and movement of Kensu-osho, his warm presence, and even the wind and light of the natural surroundings.

The lines of Kensu-osho’s robe aren’t just outlines, nor do they represent the three-dimensional form of the clothes. Their beauty is to be appreciated in their own right. If a viewer has experience writing or drawing on paper with a brush and ink, they can instinctively feel where and in what direction the artist moved the brush, and with what pressure and speed, just by looking at these lines. A painting is seen with the eyes, but it can also be re-experienced with the body.

This was a sensation traditionally unique to East Asian people. Today, we mostly use keyboards and touch screens, rather than pens and pencils, but people in pre-modern Japan used ink and brushes in their daily lives, so it would have been easier for them to imagine the brush movements.

Thus, traditional East Asian suibokuga has a unique quality of allowing the viewer to appreciate both the subject and the line itself. To further understand this uniqueness, let’s compare it with Western painting.

Comparing with western masterpieces reveals the charm of suibokuga

For a long time, Western painting had a tradition of trying not to leave any visible brushstrokes. Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece, the Mona Lisa, painted in the 16th century, was created using the technique of sfumato, where very thin layers of paint thinned with oil are applied. The viewer doesn’t see Da Vinci’s brush movements in the painting; instead, they perceive the painted Mona Lisa as an almost real person, feeling the texture of her soft skin and hair.

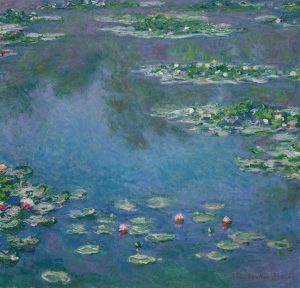

This tradition of Western painting was dramatically changed by the Impressionists in 19th-century France, such as Monet and Renoir, who were heavily influenced by Japanese art, particularly ukiyo-e (浮世絵). They squeezed paint directly from tubes and applied pure, unmixed colours onto the canvas, a technique known as divisionism.

When you look closely at Monet’s Water Lilies series, you can see that it’s made up of short strokes of various colours. We, the viewers, unconsciously blend these colours in our minds to see the overall landscape.

While the deliberate display of brushwork was a matter of course in East Asian suibokuga, it began in the West with the Impressionists. This led to the pointillist techniques of Seurat and Signac, and in the mid-20th century, to the action painting of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner. This expression technique leaves the trails of paint as it drips and splatters on the canvas, allowing the viewer to visually feel the physical movement of the artist’s body.

With these comparisons, I hope you have a renewed interest in the unique appeal of East Asian suibokuga. In our next article, we’ll delve even deeper into its charms.

Eye-catching image: National Treasure, Shorin-zu byobu (松林図屏風), Left screen. By Hasegawa Tohaku (長谷川等伯). Azuchi-Momoyama (安土桃山) period, 16th century. Ink on paper. 156.8 x 356.0 cm. Tokyo National Museum. Source: ColBase

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/art/279871/