In the middle of the Edo period, a growing number of common people began to enjoy reading, leading to a rapid expansion of publishing culture. As a result, more samurai also started illustrating books and writing, with some quickly becoming popular gesaku (戯作, playful or didactic) writers. Koikawa Harumachi (恋川春町), who is considered the founder of the Kibyoshi (黄表紙; a genre of adult picture books), was one such individual. Living in Koishikawa Kasugacho (小石川春日町) in Edo (now Koishikawa, Bunkyo Ward), he adopted the pseudonym Koikawa Harumachi—a pun on his place of residence—for his illustrations and writings. As a writer of satirical Kyoka poetry, he gained fame under the name Sake no Ue no Furachi (酒上不埒).

Adopted into the Kurahashi Family, Serving a mere 10,000-Koku Domain

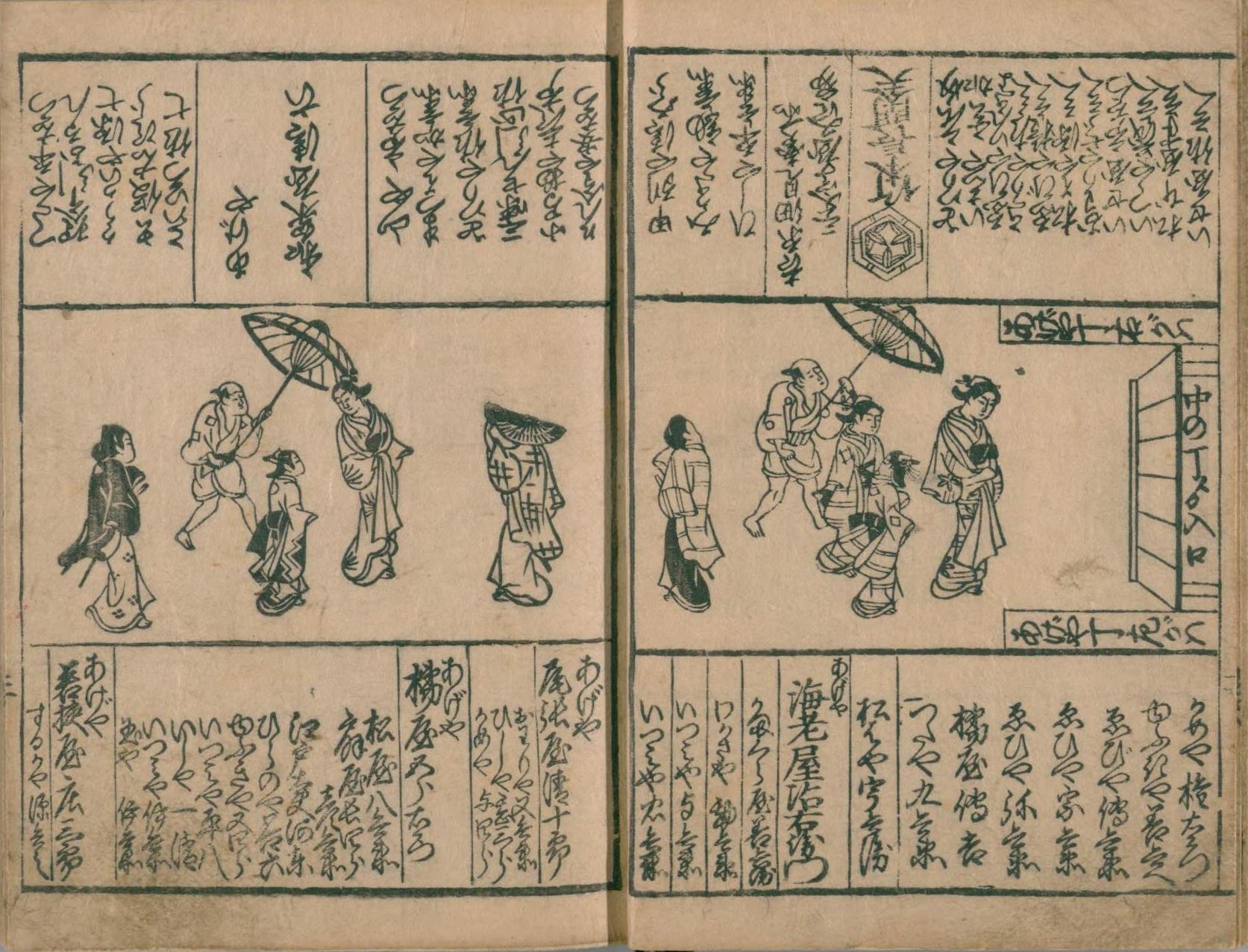

He was born in Kanpo (寛保) 4 (1744) as the second son of Kuwajima Katsuyoshi (桑島勝義), a retainer of Ando Tatewaki (安藤帯刀), a chief retainer of the Kishu (紀州) Tokugawa family. At the age of 20, he was adopted into his uncle’s Kurahashi (倉橋) family. In Anei (安永) 5 (1776), at 33, he succeeded his adoptive father upon his retirement, becoming an naiyonin (内用人) with a stipend of 100 koku (石). The year before, in Anei 4 (1775), he published ‘Kinkin-sensei Eiga no Yume (金々先生栄花夢),’ the work that instantly brought him widespread recognition. Given that he drew and wrote while still performing his samurai duties, his talent must have been extraordinary. This Kibyoshi, set in the Yoshiwara (吉原) pleasure quarter, became a massive hit. He continued to publish numerous Kibyoshi illustrated with his own drawings, and it is said that he produced around 30 volumes throughout his lifetime.

Active as an Illustrator, Having Studied Under Master Artists

Harumachi began studying painting perhaps with the intention of supplementing his income. He apprenticed under Toriyama Sekien (鳥山石燕), who is also regarded as the teacher of Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川歌麿). He was also influenced by Katsukawa Shunsho (勝川春章), who was Hokusai’s master, and it is speculated that his pseudonym, Koikawa Harumachi, was a deliberate nod to Shunsho. Subsequently, he also made a name for himself as an illustrator, such as by providing the artwork for books by his friend and fellow samurai, Hoseido Kisanji (朋誠堂喜三二) ∗1. The presence of many cultural figures in Harumachi’s circle—including Hiraga Gennai (平賀源内; a botanist, gesaku writer, and famous for producing the elekiteru, or electric generator) and Ota Nanpo (大田南畝; who was also a samurai engaging in literary activities)—must have had a significant influence on him.

Urokogataya Magobe: The Publisher Who Cultivated Harumachi’s Literary Career

Urokogataya Magobe (鱗形屋孫兵衛), played by Kataoka Ainosuke (片岡愛之助) in the 2025 Taiga drama (大河ドラマ) Berabo (べらぼう): Tsutaju Eiga no Yume-Banashi (蔦重栄華乃夢噺), was the proprietor of an established jihon donya wholesaler (地本問屋) ∗2. Urokogataya had been focused primarily on Joruri (浄瑠璃) scripts before moving on to publishing the Yoshiwara Saiken (吉原細見). The massive success of Kinkin-sensei Eiga no Yume prompted them to further venture into the Kibyoshi market, commissioning Harumachi and Kisanji to write volume after volume. However, Urokogataya’s financial situation had been deteriorating, and the inability to fully capitalise on the mainstream trends of the time led to a gradual scaling back of their business. The one who rose to prominence in their place was Tsutaya Juzaburo (蔦屋重三郎), who gained power as a publisher by issuing the Yoshiwara Saiken himself. Pressured by Tsutaya’s momentum, Urokogataya was driven to the brink of closure in Anei 9 (1780). Harumachi had also published Kibyoshi ∗3 with Tsutaya, but perhaps out of a sense of loyalty to Urokogataya, the publisher who had produced his breakthrough work, he temporarily ceased writing thereafter.

Caught in Political Upheaval: The End of a Life

Following the Great Tenmei (天明) Famine in Tenmei 7 (1787), public dissatisfaction exploded, leading to the downfall of Tanuma Okitsugu (田沼意次). Matsudaira Sadanobu (松平定信) then enforced the Kansei (寛政) Reforms, which stressed austerity and sobriety, tightening the mood of the ‘floating world’ (ukiyo). Even as publishing controls were introduced, writers like Santo Kyoden (山東京伝) and Kisanji published books through Tsutaya, almost as if in defiance of the shogunate. Harumachi, who had been on a hiatus, satirised the Kansei Reforms in Omu-gaeshi Bunbu no Futamichi (鸚鵡返文武二道), published in Kansei 1 (1789), which became a huge success. However, this incurred the shogunate’s wrath and put him in a perilous position. Similarly, Nanpo and Kisanji, who were also samurai engaging in literary activities, successively distanced themselves from the literary world and returned to their main duties. It is believed that Harumachi took his own life that year, perhaps consumed by guilt over tarnishing the reputation of the Kurahashi family, which he had inherited from his dutiful adoptive father. Due to the sudden nature of his death, rumours of suicide circulated among some. The loyal and highly talented Harumachi’s life thus ended at the age of 46. Harumachi was a man who, despite not having the most privileged background, forged and blossomed his own path through sheer talent. His was a tragic end to a life that raced through a turbulent era.

Thumbnail Image: Kinkin-sensei Eiga no Yume (金々先生栄花夢) by Koikawa Harumachi (Courtesy of the National Diet Library)

References: Edo Bungei Ko (江戸文藝攷) by Hamada Giichiro (濱田義一郎) (Iwanami Shoten), Edo no Hon-ya-san (江戸の本屋さん) by Imada Yozo (今田洋三) (NHK Books), Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (日本大百科全書) (Nipponica) (Shogakukan), Sekai Hyakka Zensho (世界百科全書) (Shogakukan)

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/rock/culture-rock/251019/