A student life full of art and international travel

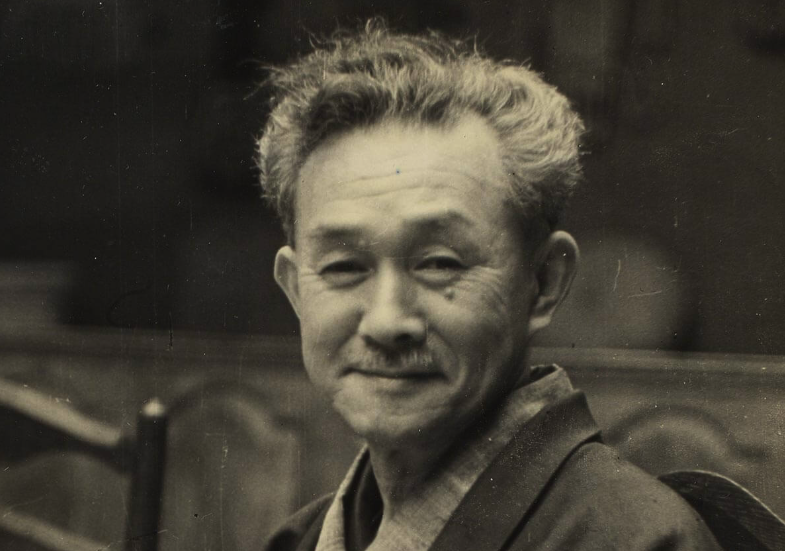

Oritayu’s family had produced many bunraku shamisen players since the Bunka and Bunsei periods. Oritayu was expected by those around him to go on to become a shamisen player, but gradually he began to feel attracted to the role of the tayu, who was known to narrate with their whole heart and soul. This desire bore fruit, and at the age of eight he was introduced to Toyotake Sakitayu (豊竹咲太夫). He took the name Toyotake Sakihodayu (豊竹咲甫太夫).

Oritayu says: “I wanted to enter the world of bunraku right after graduating from junior high school, but my grandmother and mother encouraged me to go on to high school.” He had been learning to draw since nursery and his talent for drawing blossomed during his junior high school years, so he received a recommendation to go on to art school. “In the second grade, we had nine hours of art lessons a week. It felt very free, like going to the mountains to sketch after lunch.”

With the understanding of his family and master Sakitayu, Oritayu was able to enjoy his youth. Whenever he had a long holiday, such as summer holidays, he would always travel abroad. And alone!

“When I was in my first year of high school, I crossed the American continent from east to west, north to south. I was there when the Louvre was renovated and a pyramid-shaped building was built, and I stayed in Paris for about a week. There was also the time I went to the British Museum. I think it was good that these three years of high school experience allowed me to see bunraku from an outside perspective”. In an age when the internet was not as widespread as it is today, it would have been rare for high school students to travel abroad on their own.

Days of training and working hard with no sleep

After a fulfilling high school life, Oritayu began his full-scale training as a tayu upon graduation. When asked to look back on those days, he made a surprising comment. “I have almost no recollection of the 10-odd years since I was 18.” He also said that he hadn’t had a break for about 10 years. “Once I started my training, my master changed like a demon, and I desperately tried to overcome each challenge that came my way.”

He says that she spent so much time on bunraku that she didn’t even have time to sleep, from taking care of his master’s personal needs to writing the yuka-hon ( 床本*1 ) of bunraku plays in ink and practising. He says: “I worked so hard that I couldn’t do any more, but I gutted when my master told me, ‘I can teach you joruri, but I can’t teach you motivation alone’.”

It is likely that because Sakitayu admired Oritayu’s talent, he demanded a higher level of performance from him. “I’m someone who inherently prefers take things at my own pace, so I think my master wanted to change that.”

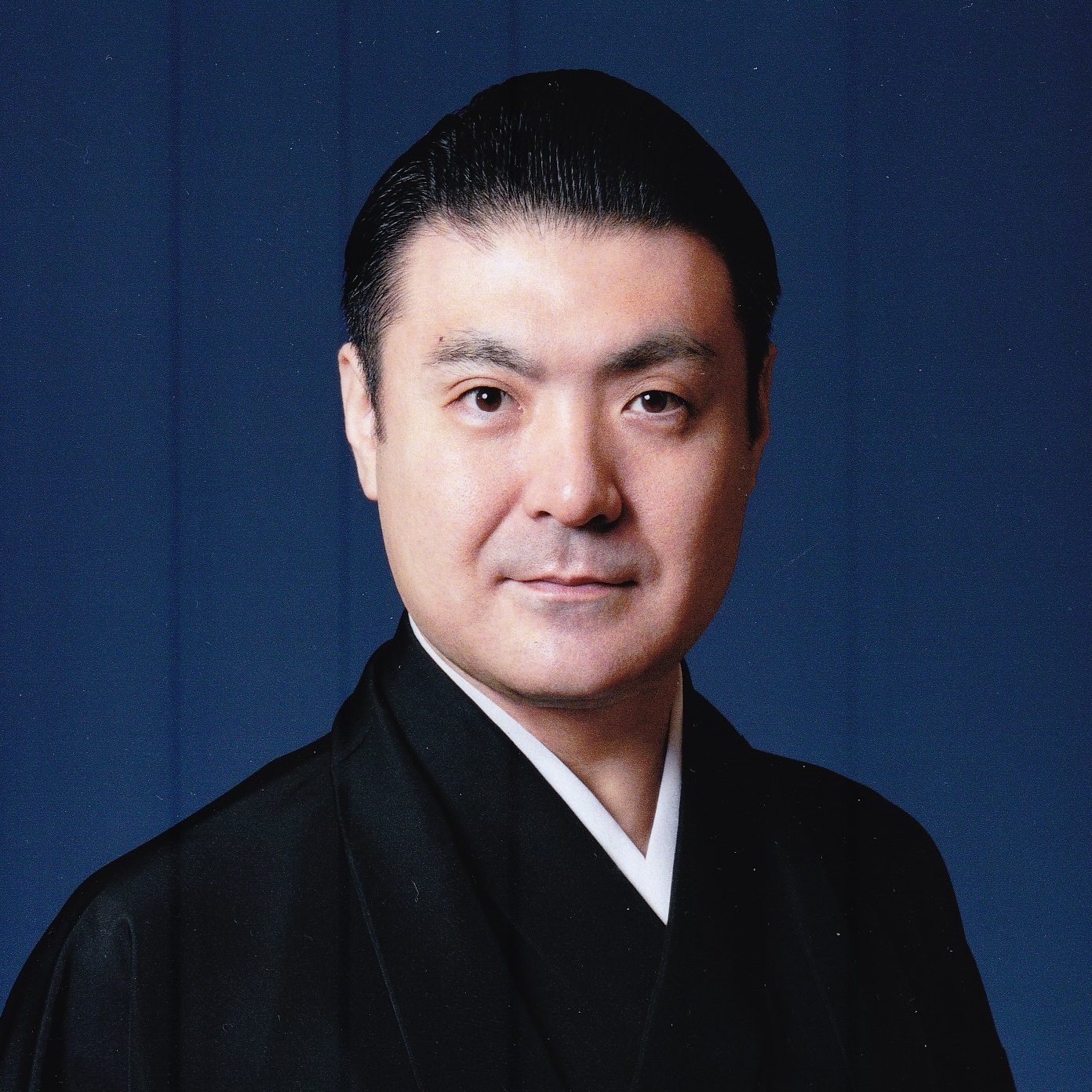

Conflicts in the process of inheriting the name of Takemoto Oritayu

Oritayu devoted himself to his art, and grew to become one of the next generation of bunraku performers who were attracting a lot of attention. When he reached the age of 40, Master Sakitayu suggested that he take over the name of his successor. It was the name Takemoto Oritayu, the former name of Sakitayu’s father, Takemoto Tsunatayu (竹本綱太夫) VIII, who was a living national treasure.

“I had been approached before, but I couldn’t respond immediately,” says Oritayu. While he was unable to make up his mind because of the big name, he was told, “I will give a memorial performance for Tsunatayu VIII on the 50th anniversary of his death, so please inherit the name at that time. I can only do so much for you”, to which he replied, “I understand”.

“Since inheriting the name, I’ve felt responsible for protecting a legacy, and that I’m going to spend the rest of my life preserving the art of Oritayu.”

The final day of work with the advice of his mentor

At the New Year Bunraku performance in January 2024, Oritayu narrated Chikamatsu Monzaemon (近松門左衛門) ‘s ‘Heike Nyogo no Shima (平家女護島), Onikai ga Shima no Dan (鬼界が島の段).’ This piece, which is also performed in Noh (能) and Kabuki (歌舞伎), depicts the despair of Shunkan (俊寛), and is considered a difficult piece requiring a high level of skill and expression.

“It was the first time for me to perform a play that my master had never performed, and ever since I was cast, he’s been worried about me. It was the first time for me to see him like that.” Master Sakitayu was not feeling well at the time, but he called Oritayu every day.

“Master called me and said, ‘Don’t let them see you as feeble.’ The character Shunkan looks old, but his actual age is 37. All it was, was that he was hungry, so you shan’t make people view him as wounded and weak.” Shunkan was exiled to Onikaiga Island (鬼界が島) after a plot to defeat the Heike (平家) clan was uncovered. Master Sakitayu’s words that illuminates the deeper perspective of this character have never left Oritayu’s mind.

This play is thought to have been revived in 1930 by Toyotake Yamashiro no Shojo (豊竹山城少掾), Tsunatayu VIII’s master. After receiving advice from Master Sakitayu that there were sound recordings of Yamashiro Shojo and Tsunatayu VIII, which he could use as reference material, Oritayu practised creating the piece from scratch with shamisenist Tsurusawa Enza (鶴澤燕三), relying on the sound recordings.

On the day of the opening night, they were informed that Sakitayu was in a critical condition. He said, “Ever since I was a child, my master had always told me that I should speak the most carefully and with all my heart at the final curtain, with the thought that I might never play this role again.” After following this instruction and giving his best performance of Shunkan, Oritayu rushed to Tokyo, where Master Sakitayu was hospitalised. “He could no longer converse with him, but he felt that his master was waiting for him.” Three days after returning to Osaka from Tokyo, where he had been hospitalised, he passed away.

“I am glad that I was able to work on the stage with the words Shunkan of my grandfather and grand master.”

Becoming the leader of supporting Wakatayu debuting performances

In April and May 2024, performances of Toyotake Wakatayu XI’s succession on his name will be held in Osaka and Tokyo. As a self proclaimed supporter of Wakatayu, he attended the memorial service for Toyotake Wakatayu I. He was accompanied to Honkyoji (本経寺) Temple, where he visited the grave and prayed for the success of the performance.

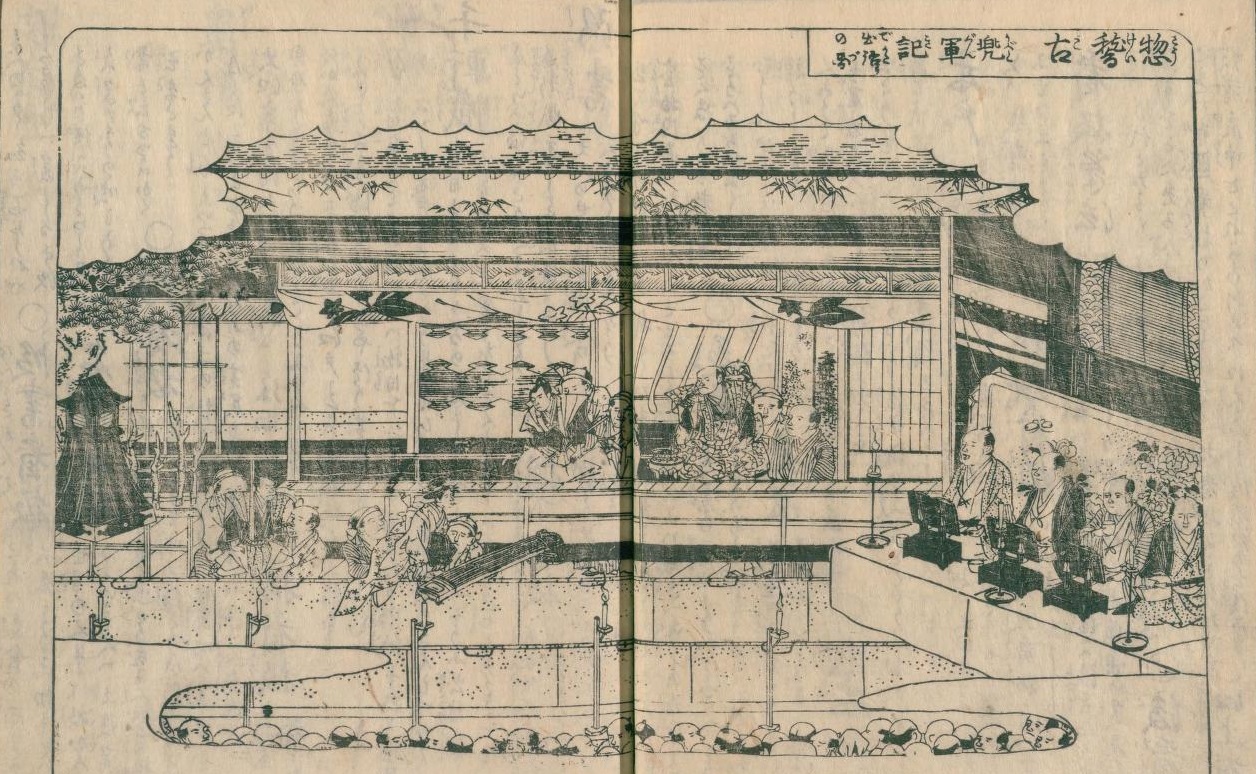

Honkyoji Temple, where the grave of Toyotake Wakatayu I is located, is about a 10-minute walk from the National Bunraku Theatre. Takemoto Gidayu (竹本義太夫), the founder of Gidayubushi (義太夫節)*2, used to have a puppet theatre called Takemotoza (竹本座) in Dotonbori (道頓堀) in Minami, Osaka. His apprentice, Toyotake Wakatayu I, launched the Toyotake-za (豊竹座). The two troupes competed with each other, and the synergistic effect is said to have made them more popular than the Kabuki theatre.

This is the first time in 57 years that Toyotake Rodayu is taking over the name, which was assumed by his grandfather. The crest on his kimono is an Edo period crest designed by the first Wakatayu, and was only permitted for Toyotake Wakatayu. At an interview, he said: “I am now grateful for the strict training I received from the masters. Now I finally understand what they told me to do”, which made me realise the depth of the art of tayu.

Toyotake Zakura, which was revived by the tayu

A weeping cherry tree called ‘Toyotake Zakura’ is planted in the precincts of Honkyoji Temple. It was planted as a memorial after the death of the first Wakatayu, but died in the middle of 1840 (at the end of the Tenpo era). The present cherry tree was planted again in 2013, the 250th anniversary of Wakatayu’s death, by volunteers from the ‘Ningyo Joruri Bunraku-za (人形浄瑠璃文楽座)’ who bear the surname Toyotake, along with the restoration of the gravestone, as a memorial service.

Oritayu, who called himself Toyotake Sakihodayu at the time, says: “I was also involved in it, so I have fond memories of it.” Toyotake Zakura, which blooms beautifully from mid-March every year, is close to the National Bunraku Theatre, so why not take a look at it when you come to Osaka?

Interview and text/Kawaratani Tokiko

Interview supported by Honkyoji National Bunraku Theatre

Takemoto Oritayu VI Information

Spotify podcast “bunraku no susume: Ori mo Ori tote (文楽のすゝめ オリもオリとて)”

X Bunraku no susume (文楽のすゝめ) official

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/240161/