The ‘grudge’ held by a lady with a flair for Chinese poetry

Most people would immediately read the Chinese characters ‘団扇’ as ‘uchiwa’ (round unfolding fan). However, upon close inspection, there are no elements of these characters that suggest that they should be read in this way.

In fact, the word originally referred to a Chinese round shaped tool, used to create a breeze, as the Chinese characters suggest (団 = round, 扇 = fan). One theory is that when these tools were introduced to Japan, used bird feathers to make them, which led to the term ‘uchiwa (打ち = beating, 羽 = feathers)’ and thus the name of the tools became widely known as uchiwa.

Han Shoyo (班婕妤), who lived in China’s pre-Han dynasty around the 1st century BC, was a courtesan with a talent for Chinese poetry. She was favoured by Emperor Cheng for a time, but was eventually forgotten, and is said to have composed a poem called ‘Onkakou (怨歌行)’, in which she compared herself to a uchiwa that was thrown away in autumn.

This poem became a favourite in later Chinese Han poetry, with the Han Shoyo itself being used as a poetic motif, and a similar trend was also true in Japan, which had learnt much from the continental poetry.

For example, Emperor Saga (嵯峨), the son of Emperor Kanmu (桓武), who founded the Heian-kyo capital and was an emperor in the early Heian period, wrote a poem entitled ‘shouyo-en (婕妤怨)’, in which he wrote: ‘A uchiwa, containing a sense of melancholy, recites a poem’. Also, the scholar-aristocrat Sugawara Michizane (菅原道真), who is said to have gone through a grudge after his death and turned into a heavenly god, in a poem titled ‘Ougi (fan)’, composed ‘round, fabric fan’ and ‘I resent the coming of autumn and hope that the season of blazing heat will continue’, clearly drawing on an anecdote from the Han Shoyo poem.

However, it must be noted here that they specifically mean the uchiwa, when the refer to the fan of the Hana Shouyo. On the other hand, the foldable fan that we now recognise as an ‘ougi (扇)’ was already invented in Japan in the Nara period, and fragments of it have been found at the Heijo-kyo (平城京) capital site. In the Japanese dictionary ‘Wamyo ruiju sho (和名類聚抄)’, which was compiled in the mid-Heian period, the terms ‘扇’ and ‘round 団扇’ are listed separately, suggesting that the two were regarded as very different by the Heian people.

Heian ougi in various roles

But that is not surprising. To us today, an ougi and an uchiwa fan are merely tools for creating a breeze, but to the people of the Heian period, the ougi was a versatile tool that fulfilled a variety of roles. The hiwougi (檜扇), an ancient Japanese ougi, is a tool made of thin sheets of cypress or cedar, strung together with a thread. It is said that the fan originated as a substitute for the sceptre used by court nobles to regulate their dignity, and many men and women carried it as one of their fashion props.

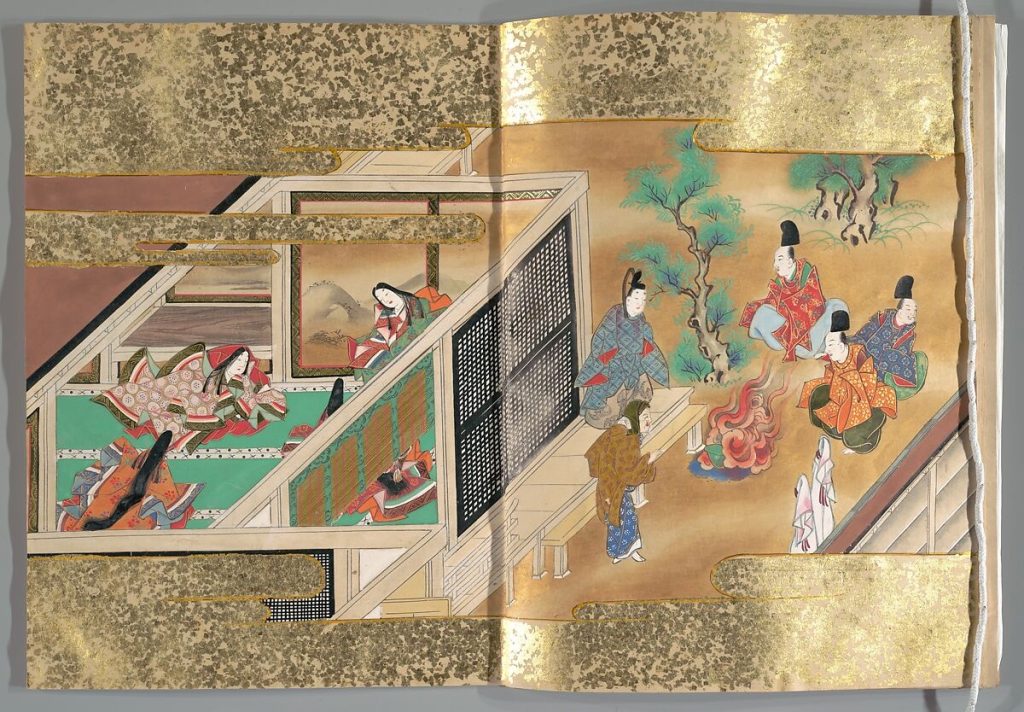

It was also used as a tool to hide one’s face or beckoning for something, and it is said that many of its owners were of high aristocratic status. A hinoki ougi made in the late Heian period is still in existence at Itsukushima (厳島) Shrine in Hiroshima Prefecture. It is made of 34 thin sheets of cypress, fastened together with silver fittings in the shape of a bird, and has a gofun (胡粉) lacquered surface with gorgeous paintings of lords and ladies, or red plum trees, etc., using iwa-enogu (岩絵の具; pigments made from crushed minerals).

On the other hand, the Kawahori ougi (蝙蝠扇) was used in a wider variety of ways than the cypress ougi: the cypress ougi bone was made thin and paper was pasted on one side. It can be said that this ougi is the closest to what we generally call a sensu (扇子) today. These ougi were less expensive than cypress ougi, and it is said that people of lesser status sometimes had one in their possession.

The Ban Dainagon Emaki (伴大納言絵巻), created at the end of the Heian period, is a picture scroll depicting a political incident called the Otenmon (応天門) government Incident that occurred in the 8th year of Jōkan (866). In one scene, depicting a fight that broke out in the town, a man dressed in a suikan sugata (水干姿), who appears to be a worker somewhere, and a monk in casual clothing without a kesa (袈裟) are each holding a Kawahori ougi in their hands.

The decoration on the inside was telling of the owners personality

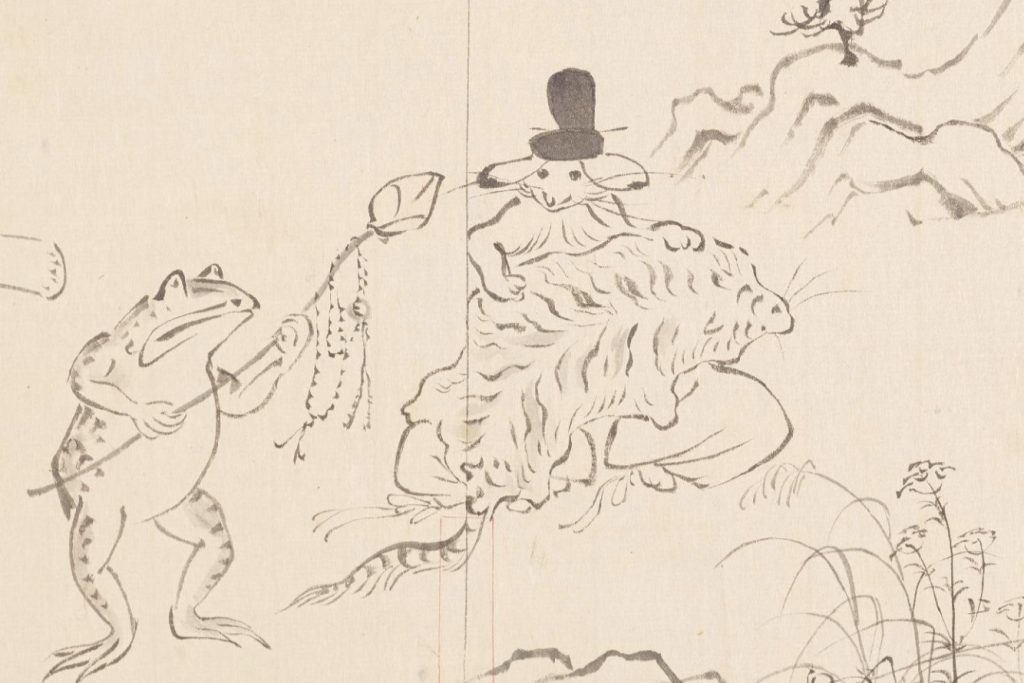

The Choju Giga (鳥獣戯画), which is thought to have been created about a hundred years before the Ban Dainagon Emaki, is still very popular today for its adorable depictions of rabbits, frogs, monkeys and other animals. However, if you look carefully at this picture scroll, you will see that they are actually holding Kawahori ougi in their hands in a variety of situations.

There is a rabbit who invites his friends carrying food for the feast with a Kawahori ougi. There is a dancing frog with a musical instrument called a binsarara in one hand and a Kawahori ougi in the other. There is a cat that covers its mouth in a look of satisfaction. There is a monkey watching from between the bones of a ougi. …… The animals depicted in The Choju Giga behave in a very folk-like manner, which suggests that their use of fan is similar to that of common people in the mid-Heian period. In other words, in this period, ougi, whether cypress fan or Kawahori ougi, were a familiar tool that we cannot even imagine today.

For this reason, ougi were apparently regarded as a true indication of their owner’s temperament. In the Tale of Genji, Momiji no ga volume (紅葉賀巻) , a somewhat unique female courtesan named Gen no Naishi no suke (源典侍) appears. When Genji receives a ougi in her hand with a ‘Kawahori with a terribly gaudy picture of a bat’, he is inwardly disappointed to see the red ground paper and a forest painted in gold and says, ‘It’s a ougi that doesn’t suit me’. The reason for this is that Gen no Naishi no suke was already in his mid-fifties at the time of the painting. In those days when a woman in her forties was considered elderly, she could be described as an old woman, and the bright red ougi must have seemed to her to be an article of questionable taste. Hikaru Genji’s honest impression must have been that she was too old for her age.

In the Azumaya volume (東屋巻) of The Tale of Genji, Kaoru (薫), the son of Genji, who has acquired a half-sister, Ukifune (浮舟), who is the exact replica of a woman he had a one-sided love for who has since died, has mixed feelings about his lover, who ‘lies with a white ougi in his hand’. This is because, to him, a pure white ougi is ominous, reminiscent of the aforementioned episode of the Han Shoyo episode, and he believes that Ukifune should naturally know of this anecdote.

It is interesting to speculate that at a time when ougi had a wide range of uses and meanings, even a person’s inner life could be inferred from the kind of ougi they held in their hand.

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/240906/