As one of Japan’s most popular artists around the world, 葛飾北斎 (Katsushika Hokusai, 1760-1849), helped formulate the image of Japan and Japanese art for many foreigners, particularly in the late 19th century. In this series, we take a look at several motifs featured in Hokusai’s artwork that exemplify the beauty of Japan, such as the new bustling capital of Edo and its rich urban culture, and the many impressive natural features found throughout the Japanese archipelago. In this article, we focus on the theme of 富士山 (Fuji-san), a mountain considered sacred since ancient times.

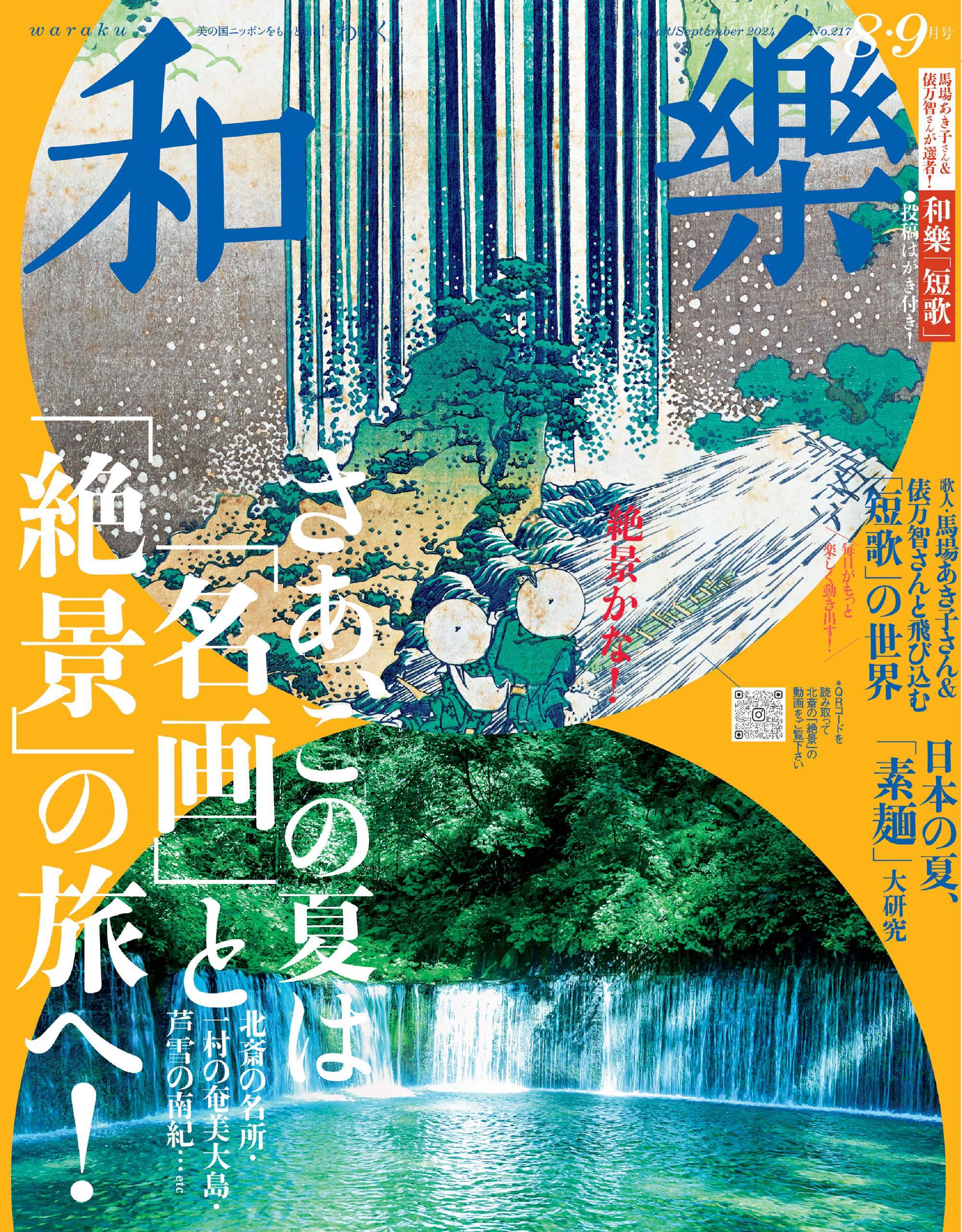

“View of Red Fuji from Lake Yamanako.” Perhaps this is the scene that Hokusai once saw—the popular “Red Fuji” dyed by the morning sun. Impressed by the holy mountain’s splendor, the artist then produced his masterpiece, 『冨嶽三十六景 凱風快晴』 (“Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji: South Wind, Clear Sky”). Photo: © MASAYUKI FUJIMOTO/SEBUN PHOTO/amanaimages

“View of Red Fuji from Lake Yamanako.” Perhaps this is the scene that Hokusai once saw—the popular “Red Fuji” dyed by the morning sun. Impressed by the holy mountain’s splendor, the artist then produced his masterpiece, 『冨嶽三十六景 凱風快晴』 (“Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji: South Wind, Clear Sky”). Photo: © MASAYUKI FUJIMOTO/SEBUN PHOTO/amanaimages

The Mount Fuji that Japanese adore became a symbol for the beauty of Japan through Hokusai’s masterpiece!

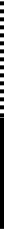

“South Wind, Clear Sky” in The Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series, oban-size, polychrome woodblock print, c.1831, Sumida Hokusai Museum.

“South Wind, Clear Sky” in The Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series, oban-size, polychrome woodblock print, c.1831, Sumida Hokusai Museum.

Within The Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series, the most well-known piece is the work commonly referred to as “Red Fuji”—though “South Wind, Clear Sky” remains the true title. The name points out that a gentle wind blows from the south, however, it is the trailing clouds in the mackerel sky that impresses viewers. Between late summer and early autumn as night approaches or when dawn begins, there is a short, magical moment when the sun sheds its red-tinged light onto Mount Fuji and dyes the mountain a spectacular red. This phenomenon is called “Red Fuji” and though it lasts for but an instant, Hokusai’s masterpiece captures the spectacle for all eternity. Surely we can appreciate it as a symbol of the beauty of Japan.

The many changing faces of Mount Fuji captured by Hokusai’s impressive drawing skills and powerful imagination

Katsushika Hokusai began working on his representative series, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, at the astounding age of 71. After its publication, Hokusai became the representative 浮世絵師 (ukiyo-e artist) for Edo, and he continued to produce works that found popularity across the globe.

Though Hokusai tried his hand at a number of landscape pictures, this series in particular received a lot of attention. As stated in the title, the series comprises of 36 images. However, due to its success, Hokusai added another 10 prints collectively known as the 「裏富士」 (Back of Mount Fuji). All together, the 46 prints make out to be quite a grand collection.

It is important to note that at the time, Mount Fuji was already a popular topic in other publications portraying its scenery and cults celebrating the holy mountain were also happening in the background. For Hokusai and other Edoites, Mount Fuji served as a symbol for Nature. Perhaps Hokusai chose the majestic form of Mount Fuji and its ever snowy peak as his main subject in this series to inspire awe in his audiences. We could say that with his great drawing skills and elaborate imagination, the genius artist took the symbol of Nature that his fellow Japanese people loved and elevated to become a symbol of Japan’s beauty.

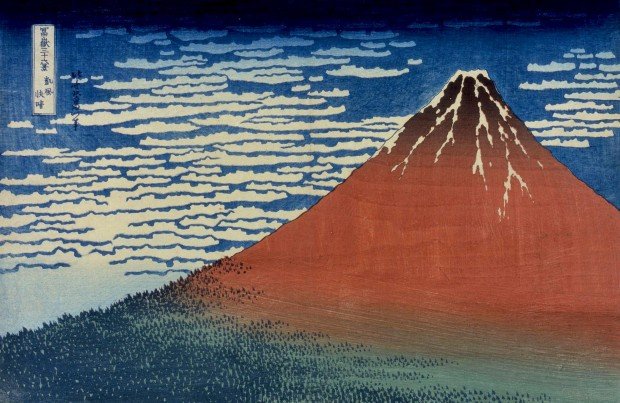

『冨嶽三十六景 相州梅沢左』 (“Umezawa in Sagami Province” in the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series), oban-size, polychrome woodblock print, c.1831, Sumida Hokusai Museum.

『冨嶽三十六景 相州梅沢左』 (“Umezawa in Sagami Province” in the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series), oban-size, polychrome woodblock print, c.1831, Sumida Hokusai Museum.

Umezawa in Sagami Province acted as a resting stop due to its location between the eighth and ninth government-designated stations of Oiso and Odawara along the 東海道 (Tōkaidō Road, a highway stretching between Kyoto and Edo). This area is believed to have been located in the town now known as Ninomiya in Kanagawa prefecture. Since the print features cranes against Mount Fuji—both recognized as auspicious omens—perhaps Hokusai created the composition with the intent for it to be displayed around New Year’s. The bold blue color achieved from ベロ藍 (bero ai, Berlin blue) ink imported from Berlin makes an impression.

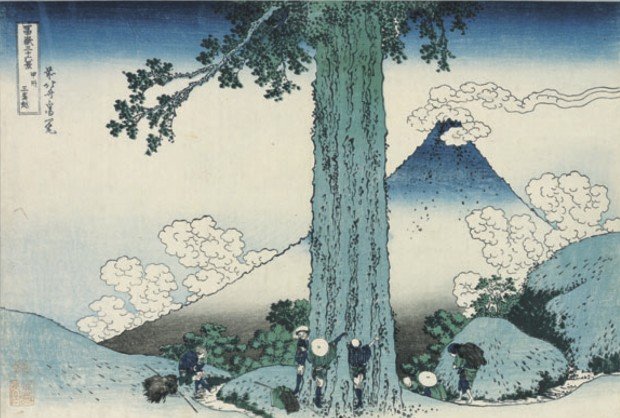

『冨嶽三十六景 甲州三島越』 (“Mishima Pass in Kai Province” in the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series), oban-size polychrome woodblock print, c.1831, Sumida Hokusai Museum.

『冨嶽三十六景 甲州三島越』 (“Mishima Pass in Kai Province” in the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series), oban-size polychrome woodblock print, c.1831, Sumida Hokusai Museum.

A giant tree attempting to overshadow the main subject, Mount Fuji, makes quite the impact. The small figures of three travelers in the foreground further emphasize the tree’s gigantic proportions in this bold composition. Mishima Pass is believed to be the Kagosaka Pass which winds from Kai Province (present-day Yamanashi), through Fujiyoshida and towards Mishima. We can sense the vibrancy of the scene from the summer clouds spilling out from around the towering peak and the rolling scenery along Kagosaka Pass.

『冨嶽三十六景 東海道江尻田子の浦略図』 (“Shore of Tago Bay, Ejiri at Tokaido” in the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series), oban-size polychrome woodblock print, c.1831, Sumida Hokusai Museum.

『冨嶽三十六景 東海道江尻田子の浦略図』 (“Shore of Tago Bay, Ejiri at Tokaido” in the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series), oban-size polychrome woodblock print, c.1831, Sumida Hokusai Museum.

The title and imagery of this work evoke the following poem from the 『万葉集』 (“Manyoshu” anthology) by the Nara period (710-794) court poet, Yamabe no Akihito.

To Tago’s coast, I see

Perfect whiteness laid

On Mount Fuji’s lofty peak

By the drift of falling snow.

As seen with this poetry, even in ancient times, Tago Bay was well-known as a spot for viewing Mount Fuji. In this print, the dramatic and distorted figures of two boats jut out in the foreground. The shape of the boats’ prows mimic that of Mount Fuji’s imposing peak and elegant ridgeline. The parallel adds an interesting tension to the scene.

Translated and adapted by Jennifer Myers.