The term 浮世絵 (“ukiyo-e”) often arises when discussing 18th and 19th century Japanese art. It is often associated with woodblock prints, but what exactly does this term encompass? Below we explore the origins of this art genre, in addition to its appeal, and 4 renown artists who helped establish ukiyo-e’s popularity across the world.

What is ukiyo-e?

The Japanese term 浮世 (ukiyo, “floating world”) refers to the world of commoners and their urban lifestyle. Ukiyo in particular emphasizes the pleasure and entertainment-seeking aspects of urban life, including 歌舞伎 (kabuki theatre), pleasure quarters, and courtesans. It also served as an ironic allusion to the Buddhist expression 憂き世 (ukiyo, “sorrowful world”). With the addition of 絵 (e, picture) to ukiyo, the term 浮世絵 (ukiyo-e, “pictures of the floating world”), is used to describe a genre of art that captured the vibrant contemporary life of townspeople. While ukiyo-e is often synonymous with woodblock prints, the genre also encompasses hand-painted works.

The genre of ukiyo-e first developed in the late sixteenth century and actually depicted the city of Kyoto, before continuing for another 300 years. With the arrival of the Edo period (1603-1868), the capital of the newly unified Japan under the Tokugawa shogunate moved to the city of Edo (present day Tokyo). Ukiyo-e took root here too, where an exciting and chic urban culture soon blossomed.

Utagawa Hiroshige, “Fireworks at Ryogoku Bridge” from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series, polychrome woodblock print, 19th century, Edo period. Image: Bridgeman Images/PPS

Utagawa Hiroshige, “Fireworks at Ryogoku Bridge” from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series, polychrome woodblock print, 19th century, Edo period. Image: Bridgeman Images/PPS

Why was ukiyo-e popular?

By the eighteenth century, ukiyo-e achieved immense popularity due to technical innovations in woodblock printing, a flourishing market for illustrated printed books, and familiar subject matter rather than employing only prescribed themes of the traditional art schools.

As previously mentioned, many themes focused on entertainment and various genres within ukiyo-e developed. Common examples include 美人画 (bijin-ga, pictures of beautiful women), 役者絵 (yakusha-e, images of kabuki actors), and compositions of landscapes, which would gain popularity later in the nineteenth century. Pictures of sumo wrestlers and warriors enjoyed popularity, too. The portraits of female beauties often featured courtesans, 芸者 (geisha, professional entertainers trained in traditional arts), and a glamorized depiction of Japan’s pleasure districts, such as Yoshiwara. By portraying contemporary popular culture, ukiyo-e art forms were embraced and forever became a part of Japan’s popular culture.

Kitagawa Utamaro’s Ten Types in the Physiologic Study of Women series, large nishiki-e brocade picture with mica-powder background. (Left) “The Fickle Type,” c.1792-1793. Image: Tanaka Machio (PPS) (Right) “Young Woman Blowing a Poppin,” c.1789-1801. Image: Alamy(PPS)

Kitagawa Utamaro’s Ten Types in the Physiologic Study of Women series, large nishiki-e brocade picture with mica-powder background. (Left) “The Fickle Type,” c.1792-1793. Image: Tanaka Machio (PPS) (Right) “Young Woman Blowing a Poppin,” c.1789-1801. Image: Alamy(PPS)

How were ukiyo-e produced?

In the beginning, ukiyo-e comprised of paintings created with 墨 (sumi, black ink) with a few colors added later. As the complexity and numbers of colors used increased, a more efficient technique was required. This necessity gave rise to the development of polychrome woodblock printing, which allowed for the mass production of a single design.

菱川師宣 (Hishikawa Moronobu, 1618-1694), an artist active around the start of the Edo period during the early decades of the seventeenth century, laid the foundation for ukiyo-e by producing single-sheet illustrations. He found great success with ukiyo-e and is often called the father of all ukiyo-e artists. While Moronobu’s works generally feature a limited color palette, 鈴木春信 (Suzuki Harunobu, 1725-1770) introduced another revolutionary change to ukiyo-e. His innovation of full color 錦絵 (nishiki-e, brocade prints) expanded the possibilities of what ukiyo-e could achieve.

Katsushika Hokusai’s “Gunkei Domestic Fowl,” polychrome woodblock print on uchiwa fan, 1835, Edo period, Tokyo National Museum. Image: TNM Image Archives

Katsushika Hokusai’s “Gunkei Domestic Fowl,” polychrome woodblock print on uchiwa fan, 1835, Edo period, Tokyo National Museum. Image: TNM Image Archives

Production of nishiki-e prints involved a team of artisans, each specialized in their own craft. First, an artist would compose a design, often with input from their publisher. Once the details were finalized, the artist would paint the master design in ink. A master carver would then cut the design onto wooden blocks. Each block was used to print a single color. Then, the printer would ink the blocks and carefully press hand-made paper onto them to add layers of color. Since printing was completely done by hand, techniques such as ink gradation and blending of colors could be achieved. Finally, the publisher who financed and promoted the project would distribute the prints. Mass production of works allowed ukiyo-e to enjoy wide circulation.

4 Ukiyo-e superstars!

With ukiyo-e’s popularity reaching new heights, some artists achieved great fame, though that did not always translate into wealth. Below are four ukiyo-e greats and the subject content with which they discovered stardom. In particular, we look at artists active during ukiyo-e’s golden years in the late eighteenth century.

喜多川歌麿 (Kitagawa Utamaro, 1753-1806)

Kitagawa Utamaro’s “Okita of the Naniwa-ya Tea House,” oban-sized multicolored print, 1793, Hagi Uragami Museum.

Kitagawa Utamaro’s “Okita of the Naniwa-ya Tea House,” oban-sized multicolored print, 1793, Hagi Uragami Museum.

The artist Kitagawa Utamaro is synonymous with portraits of beautiful women. He pioneered the bold 大首絵 (okubi-e, “large head,” bust-style portrait) composition as seen in his popular series 『婦人相学十躰』 (Ten Physiognomies of Women). This style of depiction imbues his beauties with personality and brings greater attention to their charms. During his day and still today, his works have enchanted viewers with the glamor of old Tokyo life and culture.

葛飾北斎 (Katsushika Hokusai, 1760–1849)

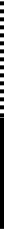

Katsushika Hokusai’s “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” from the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, oban size polychrome woodblock print, after 1831, Edo Period. Photo: Heritage (PPS News Agency)

Katsushika Hokusai’s “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” from the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, oban size polychrome woodblock print, after 1831, Edo Period. Photo: Heritage (PPS News Agency)

Katsushika Hokusai is perhaps Japan’s most popular artist, especially internationally. His immensely popular series 『富嶽三十六景』 (Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji) with its dynamic landscape compositions helped fuel a travel boom during his day and also provided inspiration to many Western artists such as the Impressionists Edgar Degas, Gustave Klimt, and Édouard Manet, in addition to Art Nouveau artists. His works including 『北斎漫画』 (“Hokusai Manga”) fed the Japonisme craze sweeping through Europe, while the print 「神奈川沖浪裏」 (Kanagawa-oki nami ura, “The Great Wave off Kanagawa”) has achieved iconic status around the world.

歌川広重 (Utagawa Hiroshige, 1797–1858)

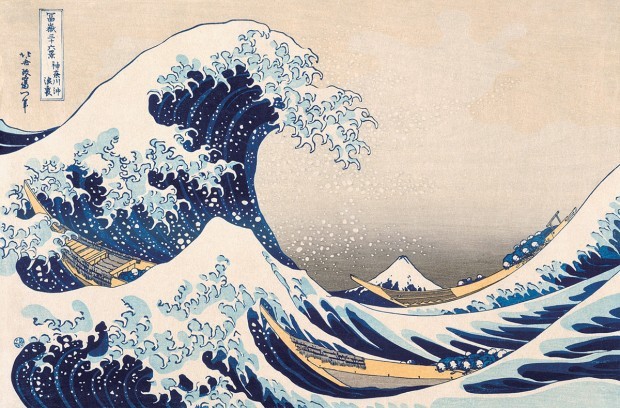

Utagawa Hiroshige, “Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake” from the series, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, multi-colored woodblock print, 1857, Takahama Tile Art Museum.

Utagawa Hiroshige, “Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake” from the series, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, multi-colored woodblock print, 1857, Takahama Tile Art Museum.

Shortly after Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series, Utagawa Hiroshige turned landscapes into a mainstream genre with his equally powerful series, 『東海道五十三次』 (The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido). From among his dramatically composed yet poetically beautiful 『名所江戸百景』 (One Hundred Famous Views of Edo) series which celebrates Edo’s culture, the print 「大はしあたけの夕立」 (“Sudden Shower over Shin-Ohashi bridge and Atake”) was copied by the French painter, Vincent van Gogh.

歌川国芳 (Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1797–1861)

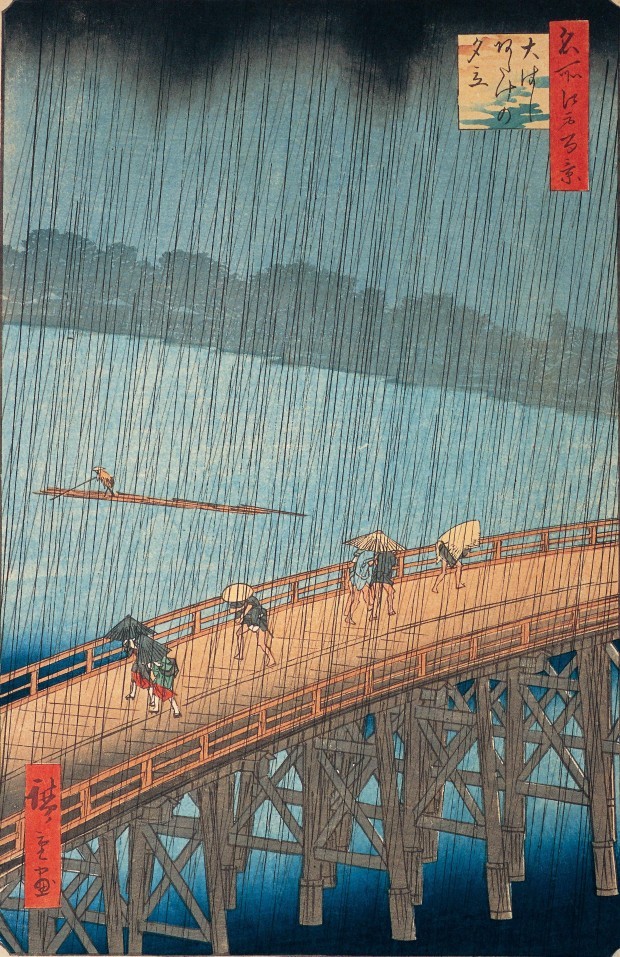

Utagawa Kuniyoshi “Mirror Images: Cats as Lion, Horned Owl, Female Demon,” pair of fan illustrations, circa 1842, Gallery Beniya.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi “Mirror Images: Cats as Lion, Horned Owl, Female Demon,” pair of fan illustrations, circa 1842, Gallery Beniya.

Though Utagawa Kuniyoshi first found acclaim with his 武者絵 (musha-e, warrior prints), his whimsical and playful designs remain among his most remembered and favorite works. The artist possessed a wide range of talents and put them to use in a variety of subjects ranging from comical caricatures to cats and the supernatural.

Ukiyo-e’s influence on the West

Ukiyo-e provided images of the relatively unknown country of Japan in the late nineteenth century, and were central to creating the West’s perception of both Japan and Japanese art. These works provided inspiration in the form of new approaches to art for early Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. These groups and their new styles of art would then found the beginnings of modern art.

The reception of ukiyo-e in the West helped cement ukiyo-e’s legacy, and this art form continues to shape the image of Japanese art both within and outside of the country today.

Written by Jennifer Myers.