Ise-katagami is a type of stencil, originally used to dye patterns and designs onto kimono (着物), such as yuzen (友禅) and komon (小紋). Craftsmen carefully carve intricate and delicate designs into a special type of paper called katagami (also known as shibugami (渋紙) or katagami (型紙)), which is made by laminating washi (和紙) paper with persimmon tannin. Its history is said to span over a thousand years.

The technique is similar in principle to stencilling, a popular printing method often used in DIY projects, where a design is cut out of a template and then ink or paint is applied through the cut-out onto a surface like paper, wood, or cloth.

In recent years, Ise-katagami has been recognised not just as a tool for dyeing, but also as a work of art in its own right, highly valued for its design and artistry. It has even attracted international buyers.

Here, we’ll introduce the charm and beauty of Ise-katagami.

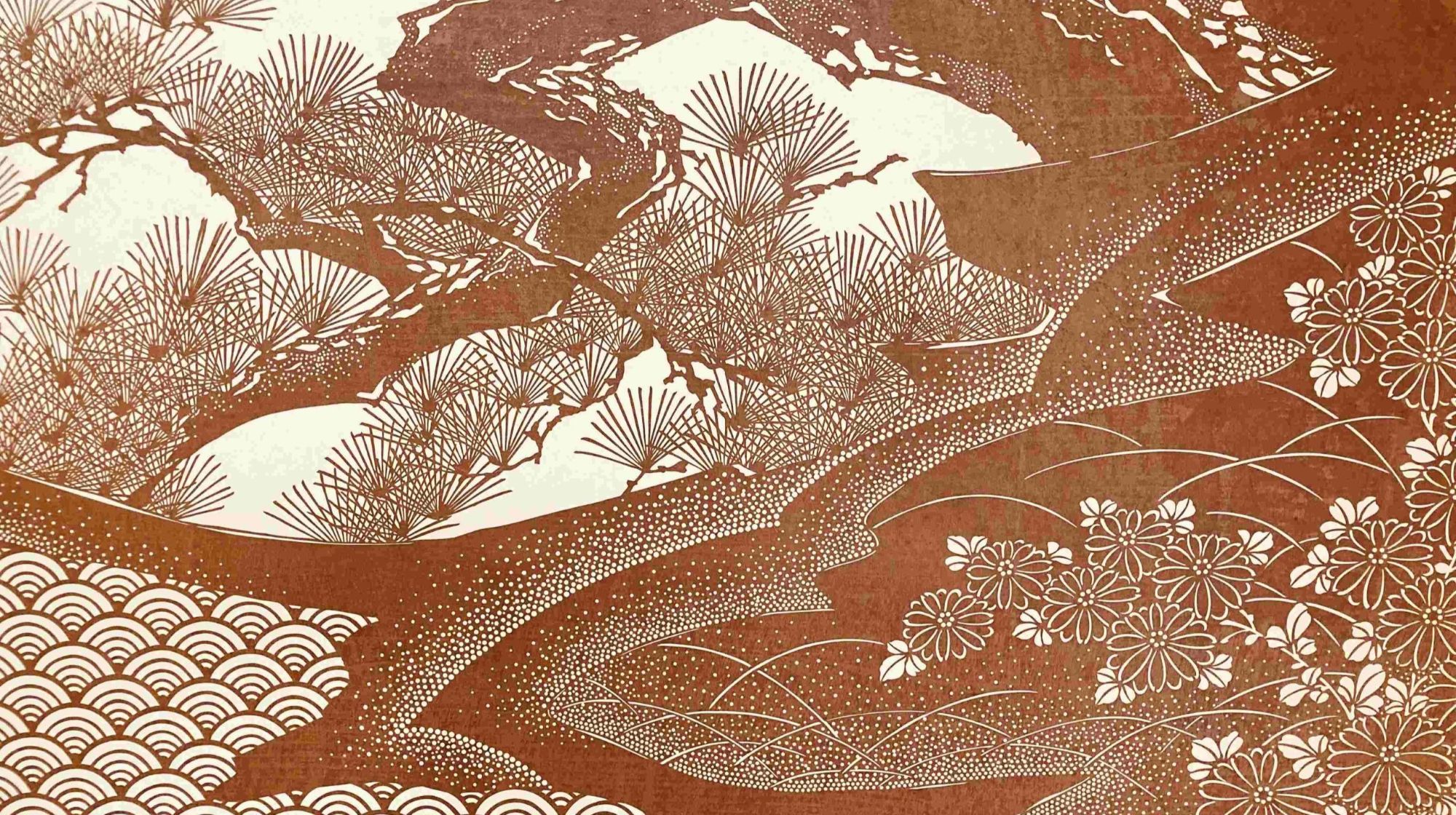

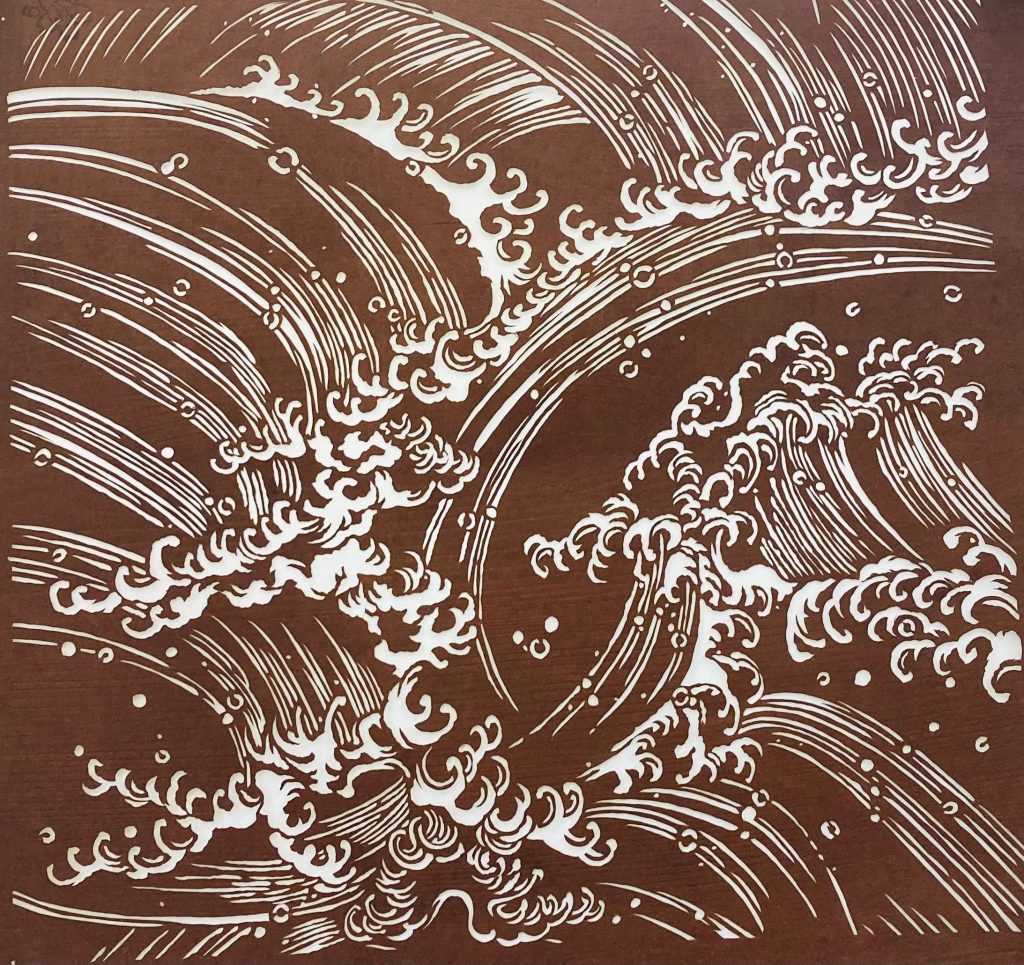

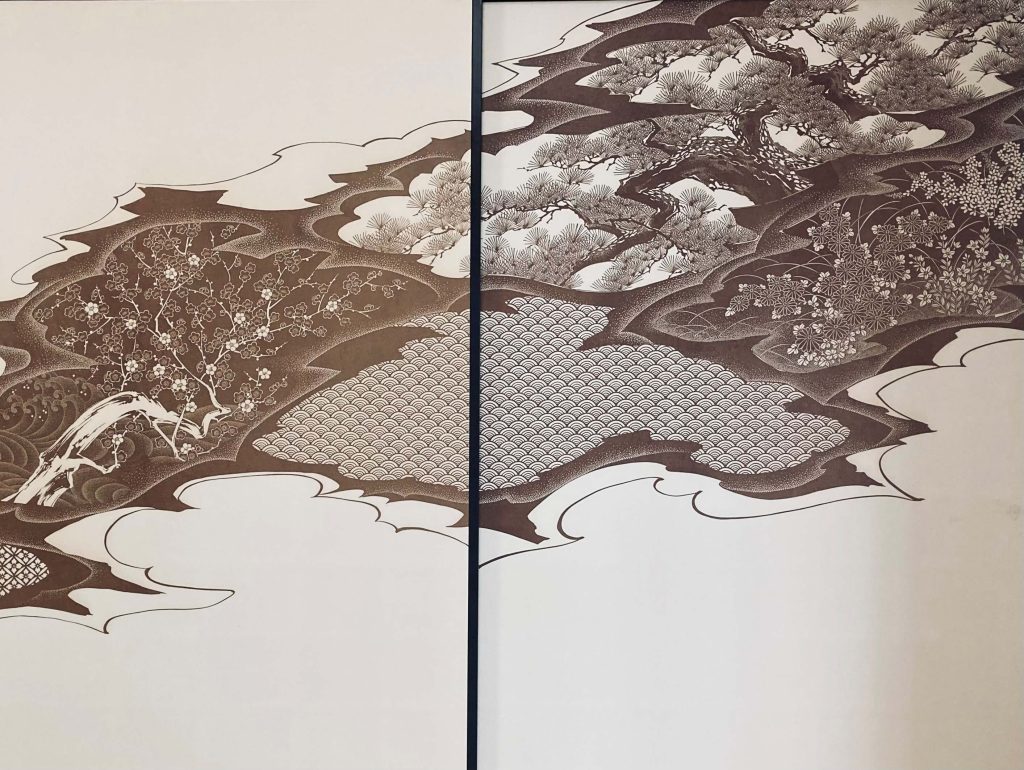

Header image: A selection of Ise-katagami patterns from the Suzuka City Traditional Industries Hall

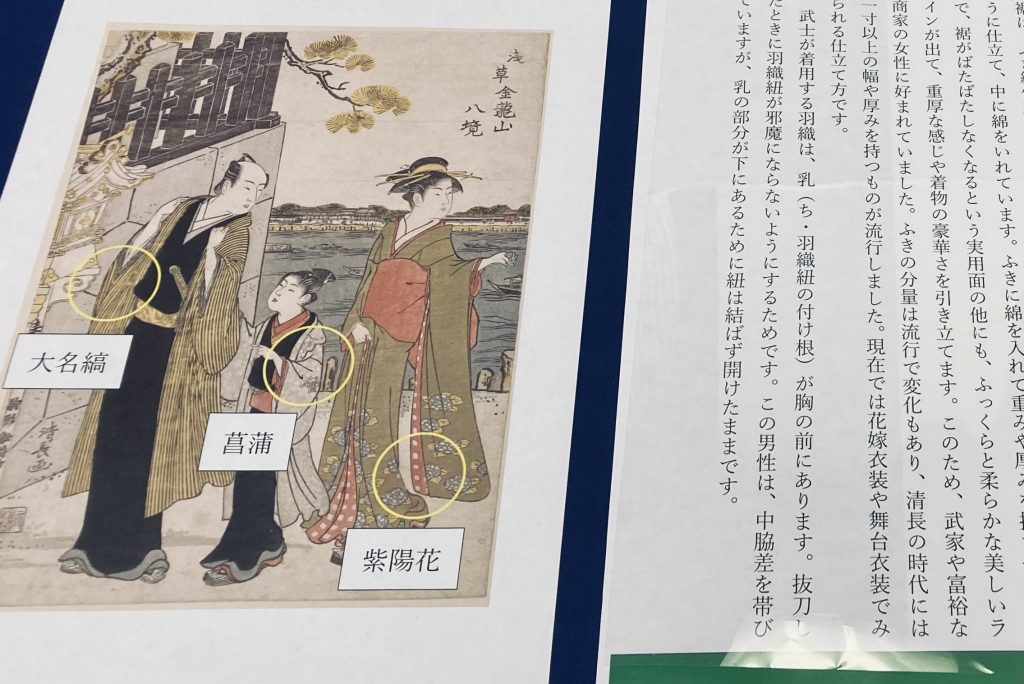

Ise-katagami in ukiyo-e prints

Recently, I visited the Suzuka City Traditional Industries Hall to see the exhibition, ‘Ise-katagami in Ukiyo-e (浮世絵)’. The exhibition showcased ukiyo-e prints by prominent Edo-period artists like Suzuki Harunobu (鈴木春信) and Torii Kiyonaga (鳥居清長), which featured accurate depictions of kimono patterns dyed using Ise-katagami.

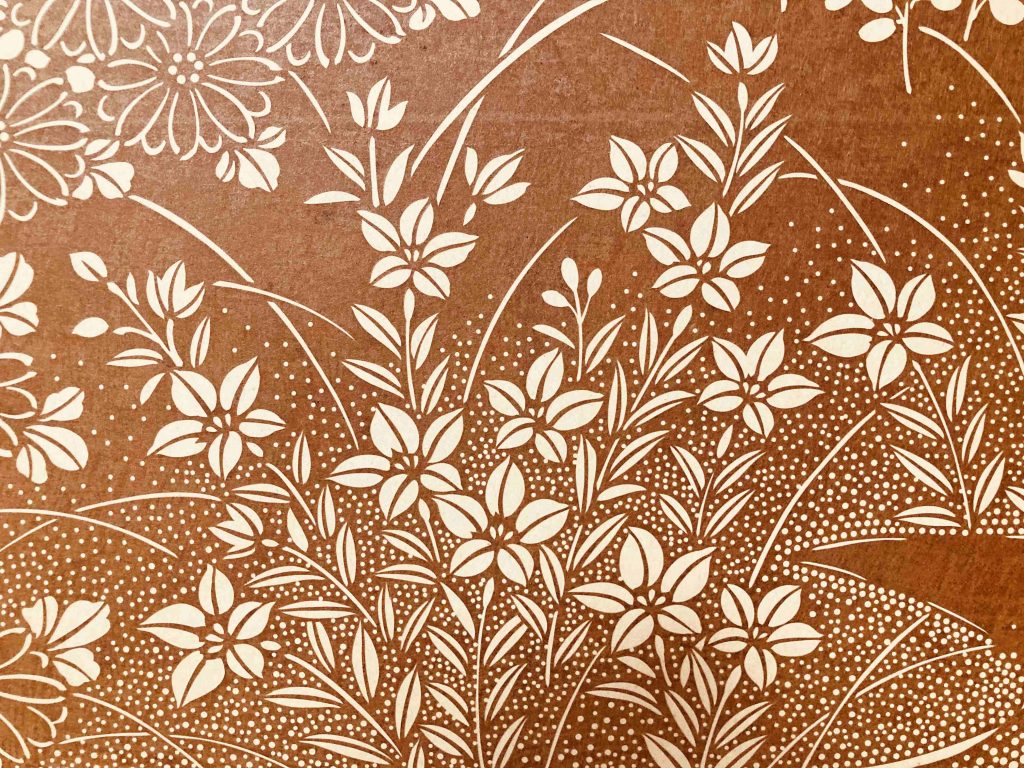

Beside the framed kimono patterns, their names were written, and the actual Ise-katagami stencils were displayed next to them. Looking at them up close, the intricacy and variety of the patterns were truly astonishing.

Ise-katagami wasn’t produced throughout the whole of Ise (伊勢) Province (Mie Prefecture), but rather was concentrated in the Shiroko (白子), Jike (寺家), and Ejima (江島) districts of Suzuka City. While dyeing techniques like yuzen, komon, chusen (注染), sarasa (更紗), and bingata (紅型) are found across Japan, over 90% of the stencils used for dyeing are carved by hand by master craftsmen, known as kata-horishi (型彫師), in these very districts. In other words, the Shiroko, Jike, and Ejima districts are responsible for producing most of the dyeing stencils used throughout Japan.

The exquisite and intricate patterns of Ise-katagami

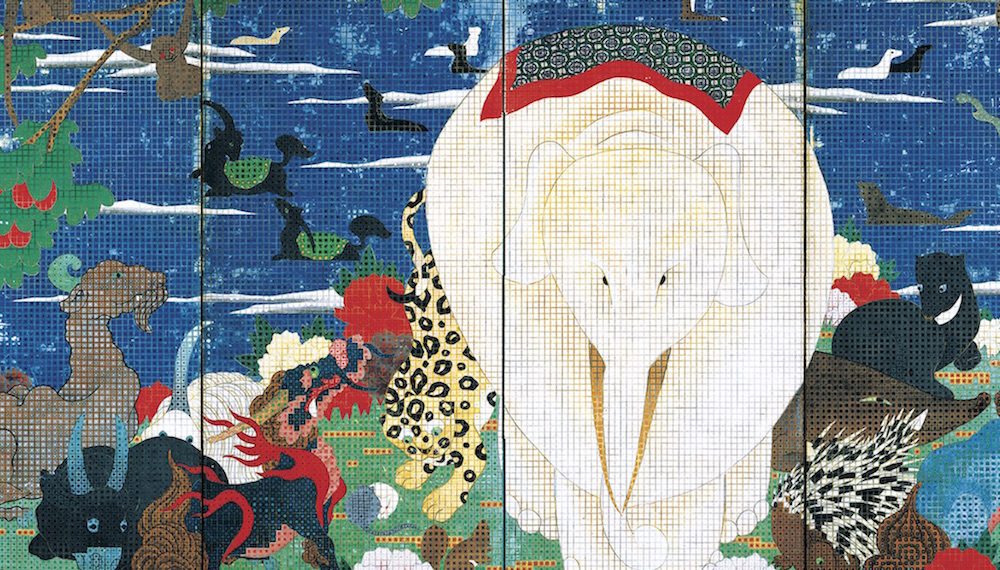

For centuries, the Japanese people have found beauty in nature—the flowers, birds, wind, and moon—the changing seasons, and even in everyday objects, and have expressed them as traditional designs. The delicate and graceful patterns of Ise-katagami were born from these motifs, but sometimes they also drew on new ideas to create modern and innovative designs.

Note: The explanations of the stencils are provided by the NPO rekishi to bunka no aru takumi no mieru sato no kai (歴史と文化のある匠の見える里の会).

Carving the katagami template

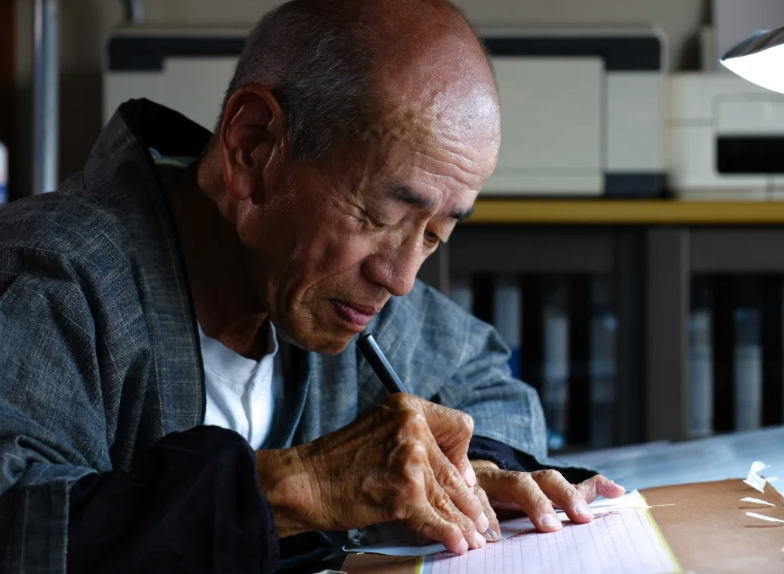

The craftsmen behind the art form

On the day of my visit, my guide was Nasu Keiko (那須恵子), a kata-horishi (型彫師, stencil carver) also known as ‘Kataya 2110’.

I first learned about Ms Nasu at an exhibition of works by Rinku (凛九), a group of female traditional craftswomen active in the Tokai (東海) region, held in Yokkaichi (四日市) City. I was captivated by the beauty of her Ise-katagami, which I was seeing for the first time, and also intrigued that she was from the same prefecture as me, Gifu (岐阜), and had worked as an illustrator in the design department of a printing company there. The awe I felt on that day led to this very interview.

The special paper used for Ise-katagami, known as katagami, is made with Mino (美濃) washi paper. Three sheets of Mino washi are laminated together with persimmon tannin to form a board-like material. It is then sun-dried and smoked for about a week in a smoking room. After this, it’s dipped in persimmon tannin again, sun-dried, and smoked once more, then aged for about 40 days. The result is the paper used for Ise-katagami.

This is where the work of a kata-horishi begins. By carving the designs out of the katagami, they create the stencils, or templates, for dyeing. They sit and carve on their workbenches for hours on end. It can take anywhere from a few days to several weeks to complete a single stencil, and sometimes even over a month.

The techniques of Ise-katagami

Ms Nasu explained the different techniques of Ise-katagami.

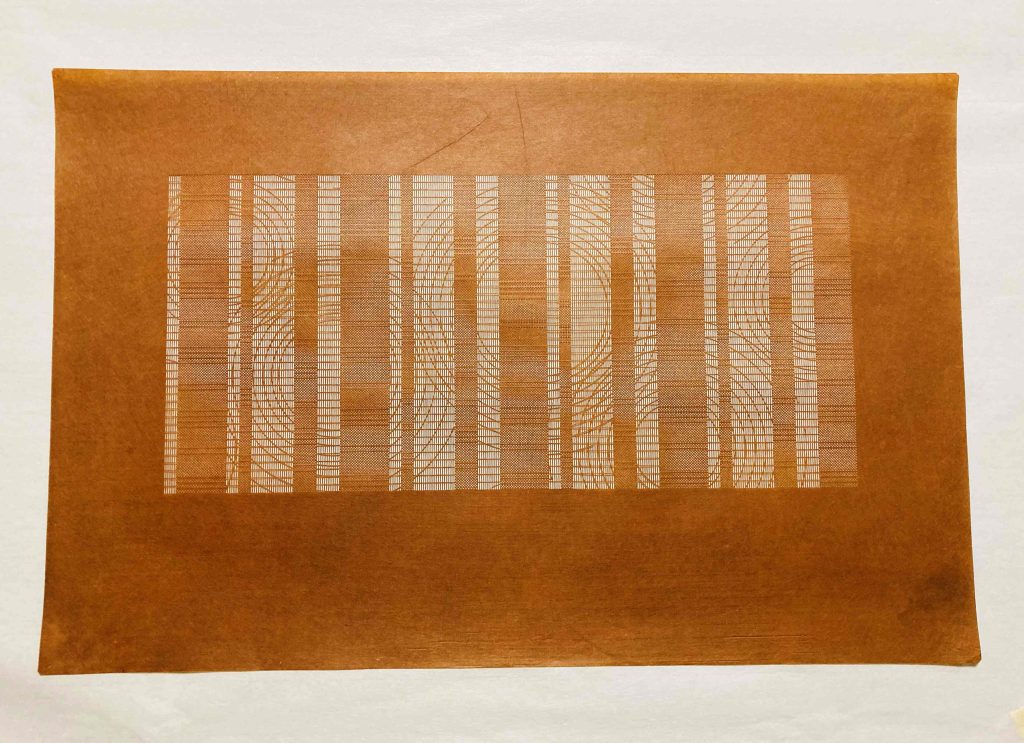

“There are four main carving techniques in Ise-katagami. Shima-bori (縞柄) is used for carving stripes with a ruler and a chisel. Tsuki-bori involves thrusting a chisel forward in a vertical motion. Dogu-bori (道具彫り) uses specialised chisels in various shapes like flowers, fans, or diamonds, to carve a shape in a single thrust. Finally, kiri-bori uses a semi-circular-bladed chisel, held vertically, which is rotated to carve small holes that form patterns. All these techniques involve carving through multiple layers of katagami at once. Apprentices train under a master and inherit their techniques. It takes many years of experience to master a single technique, and most craftsmen only specialise in one or two. The carving tools are also extremely important and are often made by the kata-horishi themselves. The quality of the tools can make a world of difference to the final work.”

Ms Nasu’s master was the late Ikuta Yoshinori (生田嘉範), a kata-horishi who specialised in tsuki-bori.

After leaving her job at the design company in Gifu, Ms Nasu was searching for a lifelong career. Through a friend’s introduction, she discovered Ise-katagami. She moved to Suzuka and became a pupil of Mr Ikuta, beginning her apprenticeship as a kata-horishi. Fifteen years have passed since then. Sadly, Mr Ikuta has since passed away, but Ms Nasu, along with her fellow apprentice, Ms Maruta (丸田), continues his work in the inherited studio. She also takes on a promotional role for Ise-katagami and has been recognised for her achievements, including designing and creating the katagami for the Mie Prefectural Handbook. In 2021, she was honoured by Mie Prefecture as a ‘Mid-career Outstanding Craftsman’.

The history and allure of Ise-katagami

The origins of Ise-katagami

It seems odd that Ise-katagami originated in Suzuka, which is not a major producer of the washi paper needed for the stencils, nor is it a major dyeing district.

There are various theories about its origin, some of which have become almost legendary.

Jike, in Suzuka City, is home to the Koyasu Kannon-ji (子安観音寺) Temple, said to have a history of 1,300 years. Let me share an interesting story I heard from Goto Taisei (後藤泰成), the temple’s chief priest and also the chairman of the NPO rekishi to bunka no aru takumi no mieru sato no kai (歴史と文化のある匠の見える里の会), which promotes community revitalization by preserving and sharing local history, culture.

“Our temple was built by an imperial decree from Emperor Shomu (聖武) and has long been a site of worship for safe childbirth. There’s a cherry tree in the temple grounds known as the fudan-zakura (不断桜), which is said to be perpetually in bloom and full of leaves, a sign of the divine power of Kannon (観音), the temple’s main deity. The story goes that during the Onin (応仁) War, an old man named Kudayu (久太夫), who had built a hermitage near the temple, was inspired by the beautiful patterns left by insects on the leaves of this fudan-zakura. He began cutting designs into paper with a small knife, and this is said to be the beginning of Ise-katagami.”

A similar story is told about the fukie (富貴絵), a type of paper-cutting art sold as a souvenir at Koyasu Kannon-ji.

“Far back in the Ashikaga (足利) period, a nobleman, Hagiwara Chunagon (萩原中納言), fled the turmoil in Kyoto and sought refuge at the temple with a close friend, the high priest Hoin (法印). To pass the time, he carved patterns of flowers and birds with a small knife and sold them to worshippers as souvenirs, which became the prototype for fuki-e.”

It seems difficult to pinpoint the exact origin of Ise-katagami. According to an article by Morimoto Takashi (森本孝), ‘Tracing the Origins of Edo-period Ise-katagami,’ from the catalogue of the 1993 Ise-katagami Exhibition at the Mie Prefectural Art Museum, it’s believed that the stencil carving technique was brought from Kyoto to Shiroko in Ise around the time of the Onin War, when many people fled the conflict in Kyoto to seek refuge in the area.

Ise-katagami preserved under the patronage of the Kishu Tokugawa clan

Entering the Edo period, the stencil dyeing technique developed significantly as the villages of Shiroko and Jike were incorporated into the Kishu (紀州) Domain, one of the three main branches of the Tokugawa (徳川) family. An officially recognised kabunakama (株仲間, guild) of stencil sellers was formed, which monopolised the market and established a nationwide sales network. The Kishu Domain provided various benefits, such as permits for itinerant merchants and travel passes (tori-kitte; 通り切手). The tori-kitte served as both a checkpoint pass and a certificate that goods were considered official. Under the strong patronage of the Kishu Domain, Ise-katagami was able to maintain its high quality and pass on its techniques to future generations.

Suzuka is on the Ise Road (Ise-kaido), a route to the Ise Grand Shrine (Ise-jingu; 伊勢神宮), and Shiroko, in particular, was a post town along this road. The Ise Road branches off the Tokaido (東海道) Road at Hinaga no Oiwake (日永の追分), at the southern end of Yokkaichi (四日市), and heads towards the Ise Grand Shrine. Towards the end of the Edo period, pilgrimages to ‘Oise-san (お伊勢さん)’ became very popular, and many people from all over Japan visited Shiroko as they made their way there. A road where people come and go is also a crossroads of diverse cultures. The meeting and fusion of different cultures may have triggered unexpected new possibilities to emerge, stimulating the kata-horishi to pursue even greater beauty.

Edo-komon: the discreet fashion of the daimyo

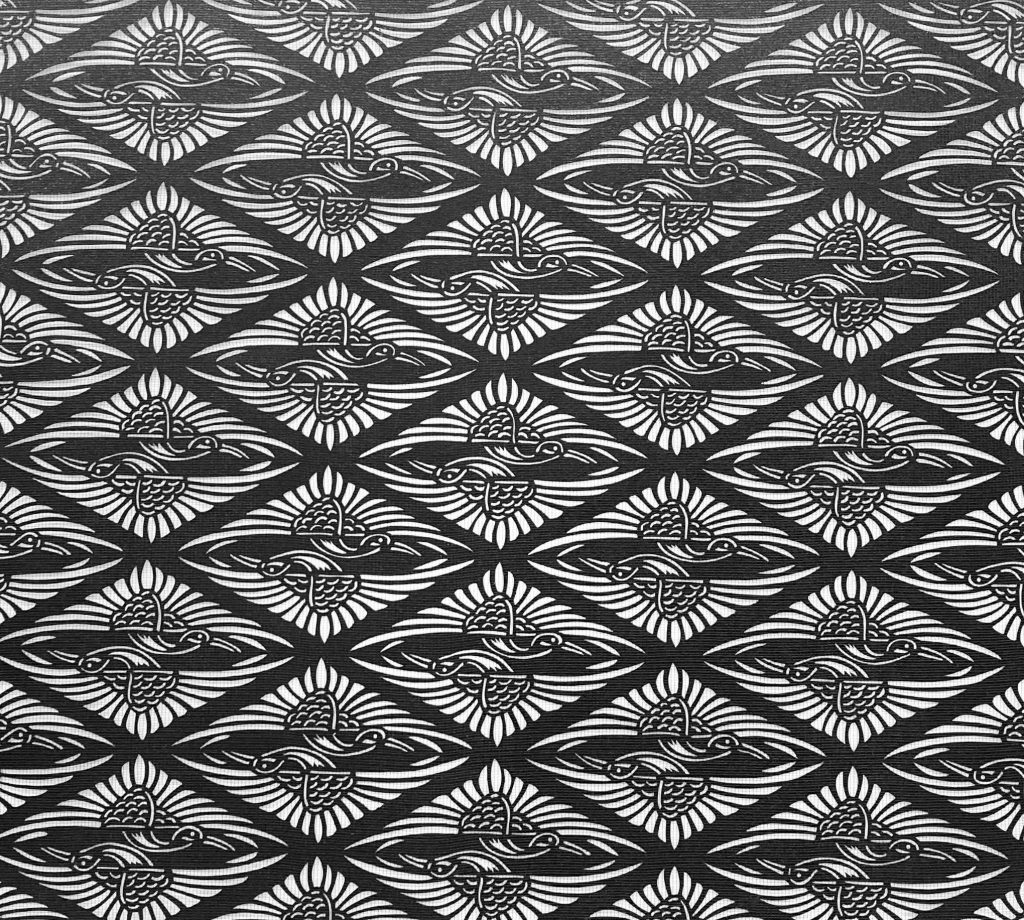

Ise-katagami features a diverse array of patterns. Besides natural motifs like flowers, birds, wind, and the moon, they also include designs of musical instruments, toys, and traditional auspicious patterns like seikaiha (青海波), kikko (亀甲), and ichimatsu (市松, checkered patterns). The charm of these designs lies in the subtle wobbles and warmth of the lines created by human hands, something that cannot be replicated by machine carving.

The term komon refers to a type of pattern where the same design is repeatedly dyed onto a fabric in one direction, making it clearly visible. Among these, Edo-komon is a style where the patterns are so incredibly small that the fabric appears to be a single colour from a distance. These are single-colour dyes, and some stencils have as many as 100 holes carved into a one-centimetre square. The finer the pattern, the more difficult the technique and the higher its status.

Edo-komon, which could not exist without Ise-katagami, was used for the formal kamishimo (裃) attire of the feudal lords (daimyo) during the Edo period. It was a form of discreet fashion that emerged after the shogunate prohibited ostentatious clothing with vibrant colours and patterns.

The most prestigious Edo-komon patterns are known as the ‘Edo-komon Sanyaku (江戸小紋三役)’: same (鮫), gyogi (行儀), and toshi (通し). Furthermore, each daimyo family had specific patterns they were allowed to use (sadame-komon; 定め小紋). The people of Edo, with their keen eye for style, did not miss this trend, and Edo-komon eventually spread among the common people as a chic and refined fashion statement.

Ise-katagami at the forefront of Japonisme

Following the Meiji Restoration, the feudal system collapsed, and Ise-katagami lost the protection of the Kishu Domain. The guild system was dismantled, and the craft was at the mercy of the changing times. However, its beauty captivated foreigners visiting Japan. Philipp Franz von Siebold, a German physician and naturalist, purchased a large number of Ise-katagami stencils and took them back to Europe, along with ukiyo-e prints and botanical specimens. It’s well known that in the latter half of the 19th century, a great movement known as Japonisme swept through Europe and eventually spread worldwide, and Ise-katagami played a significant role in this.

Ise-katagami was recognised not only for its aesthetic as a decorative art form (known as KATAGAMI) but is also believed to have greatly influenced artistic movements such as the Arts and Crafts Movement, advocated by the poet, designer, and socialist William Morris in Britain, and Art Nouveau, which emerged in France.

During a time when Japan was desperately trying to catch up with and surpass Western countries, neglecting its own culture, Europe was taking great interest in Japan’s traditional arts and crafts.

Today, thousands, and in some cases, over 10,000 Ise-katagami stencils are housed in museums across Europe and the United States. Why didn’t the Japanese people recognise their beauty? Because for the Japanese, Ise-katagami was not an object of appreciation, but merely a tool for dyeing. The stencils that Siebold and others took back were meant to be discarded after their purpose was served. The Japanese people of that time must have been baffled as to why anyone would want such things.

The kata-horishi who cultivated the tradition of Ise-katagami

Ms Nasu explained:

“There are no signatures on the Ise-katagami stencils that still exist today. In the past, the names of kata-horishi were not made public. They were not artists, but craftsmen who supported the dyers. Their unwavering focus was on creating the best stencils possible. This was the spirit of the kata-horishi, a spirit that I hope people can feel is still alive today.”

The rich and diverse Japanese culture embodied in Ise-katagami has been passed down to the present day through the tireless work of these nameless craftsmen.

The late Komiya Yasutaka (小宮康孝), a leading figure in Edo-komon and a Living National Treasure, was taught by his father, the late Komiya Kosuke (小宮康助, also a Living National Treasure), that “to ensure the survival of Edo-komon, it is essential to respect the stencil craftsmen.” Komiya Yasutaka went on to meet the late Kita Torazo (喜田寅蔵), a master among masters of Ise-katagami carving, and together they created numerous masterpieces.

The future and preservation of Ise-katagami

The biggest challenge for any traditional craft is the preservation and succession of its techniques. The world of Ise-katagami is no exception.

At one point, there were said to be as many as 350 kata-horishi, but their numbers have fluctuated due to changes in lifestyle and the effects of war. Currently, 13 craftsmen are certified as Traditional Craftsmen of Ise-katagami. Organisations like the Ise-katagami Technical Preservation Association, a holder of Important Intangible Cultural Properties, and the Ise-katagami Cooperative Association, formed by businesses that sell paper, yukata (浴衣), and kimono using Ise-katagami, are working to train successors and pass on the techniques.

Nasu Keiko is a member of the Ise-katagami Carving Association. She is also part of Rinku (凛九), the Katakoto-no-kai (カタコトの会, a group of people who make, use, and love Ise-katagami), and Tokowaka (常若, a group of young craftsmen based in Mie), and is an active member of the NPO rekishi to bunka no aru takumi no mieru sato no kai.

Having previously worked in the design department of a printing company, Ms Nasu sometimes uses digital methods to create stencil designs. The saying “tradition is a series of innovations” rings true. Instead of simply following the old ways and techniques, one can preserve the most important aspects while adapting and improving to the changes of the times, thereby creating new values and creations. With talent like Ms Nasu, Ise-katagami will likely give birth to a new world of aesthetics.

Ms Nasu’s motto is ‘to support the dyers and convey emotions through stencils for 100 years to come.’ This devotion, akin to a prayer, will open the door to the future of Ise-katagami.

Research Assistance:

Koyasu Kannon-ji Temple (子安観音寺)

Ise-katagami Kataya 2110, Keiko Nasu

Suzuka City Traditional Industries Hall

3-10-1 Jike, Suzuka City, Mie Prefecture 510-0254

Tel:059-386-7511

References:

Mie Prefectural Art Museum: Morimoto Takashi (森本 孝), ‘Tracing the Origins of Edo-period Ise-katagami’

Government Public Relations Online: ‘The Patterns of “Ise-katagami” that Captivated Europeans’

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/craftsmanship/220170/