A beautiful woman cloaked in mystery

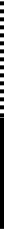

Take a look at this scroll painted by Seikei in the late 19th century. An elaborately dressed woman stands with her back towards the viewer, but glances back over her shoulder. Her bold and beguiling stare catches our attention. As the viewer’s eyes follow the movement of her hand which playfully lifts up the uchikake (over kimono) that covers her form, the viewer notices that the sumptuous silk is decorated with fearsome images. Depictions of Hell in fact. Just who is this mysterious beauty wrapped up in such frightening imagery?

The Hell Courtesan was popular during times of turmoil, representing our struggles

“The Hell Courtesan” by Seikei, late 19th century, ink and color on silk, hanging scroll, H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer. Image: Metropolitan Museum

“The Hell Courtesan” by Seikei, late 19th century, ink and color on silk, hanging scroll, H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer. Image: Metropolitan Museum

In the Edo period (1603-1868), a legendary beauty known as Jigoku Dayū frequently appeared in popular literature and then art. In particular, the otherworldly figure often featured in woodblock prints and paintings during the political turmoil in the latter part of the Edo period and through Japan’s transition from a feudal land to modern state in the Meiji period (1868-1912).

Jigoku Dayū literally means “hell courtesan,” and she is depicted as a beautiful, high-ranking courtesan dressed in elegant kimono and an over kimono with images of Hell according to Japanese Buddhist mythology. In the above image by Seikei, we can make out Emma-Ō, the overlord of Hell, in the center ready to judge the next sinner that arrives. Surrounding him and cleverly arranged along the folds of the kimono are demons who will dole out the punishments to each soul sentenced by Emma-Ō.

Jigoku Dayū wears her obi sash tied in the front, which denotes her status as a courtesan, and on it are a different, contrasting set of images. Her green obi depicts a bodhisattva and various heavenly attendants coming down from the Pure Land to save souls.

Kawanabe Kyōsai’s Hell Courtesan takes on the Demon King

“Emma and the Hell Courtesan” by Kawanabe Kyōsai, ink and color on silk, hanging scroll, late 19th century, Etsuko and Joe Price Collection.

“Emma and the Hell Courtesan” by Kawanabe Kyōsai, ink and color on silk, hanging scroll, late 19th century, Etsuko and Joe Price Collection.

One of the most popular artists active during the late Edo and Meiji periods was Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831-1889). While his works ranged from humorous caricatures to exquisite classical-style paintings, among Kyōsai’s works are numerous depictions of Jigoku Dayū as well. Here is one example of his many Hell Courtesan-themed pieces.

In this painting, we find the Hell Courtesan standing before Emma-Ō and his mirror, which reflects the former sins of deceased people who do not repent before entering Hell. The lord of Hell is painted with broad brush strokes, while in contrast, the Hell Courtesan is drawn with thin, delicate lines. Though Emma-Ō sneers down on the Hell Courtesan, she appears composed, unafraid, and even seems a bit boastful as she stares down the Demon King. How can she be so confident?

The answer lies with the hossu (Buddhist whisk) she clutches in her hand. This whisk was used by Zen Buddhist masters and represents that she has achieved enlightenment. Though this image and the Hell Courtesan folklore appears to combine both Pure Land Buddhist and Zen Buddhist concepts, it is meant that as an enlightened being, the Hell Courtesan will not suffer the torture of Hell. In Zen Buddhism, this means that she will not be deluded and her mind will no longer struggle against what is real and imaginary.

How did the Hell Courtesan achieve enlightenment though?

Jigoku Dayū first showed up in literature in an anonymous book of humorous short stories in 1672 title “Ikkyū kantō banashi.” From the beginning, she was connected to the iconoclastic and eccentric Buddhist monk, Ikkyū. The short story narratues how Ikkyū went to Sakai in present day Osaka and met the Hell Courtesan at an inn during his travels. The two exchanged poetry on living in this world, and Ikkyū was impressed by her skills. The Hell Courtesan then makes a joke about how, “There are none who avoid falling into hell,” which refers to all those who had gone astray and fallen in love with her.

The original writings related to Ikkyū were written in the Japanese version of Chinese known as kanbun, which common people could not read. Over time, many legends sprung up around the monk which drastically differed from the earlier tales. The aforementioned story is one of those fictional fables thought to have been made up by an author. Due to the success of this tale, the Hell Courtesan continued to appear in common literature and her story expanded greatly.

It was the beloved writer Santō Kyōden’s version of the Hell Courtesan in 1809 that both cemented her popularity and created her image that would be copied for years to come. In his version, Ikkyū encountered the Hell Courtesan when he visited a brothel. Since he consumed fish and drank alcohol, the Hell Courtesan doubted his validity as a monk. (At the time, monks were forbidden from eating meat let alone visits to pleasure quarters as these were earthly desires.)

“Hell Courtesan and Ikkyu” from Kawanabe Kyosai, 1871-89, ink, color, and gold on silk, the Israel Goldman Collection.

“Hell Courtesan and Ikkyu” from Kawanabe Kyosai, 1871-89, ink, color, and gold on silk, the Israel Goldman Collection.

As a result, the Hell Courtesan devises a plan to send in dancing women and musicians to test the monk and reveal his true intentions. As she spied on the party from behind a screen, she saw that Ikkyū was dancing with a group of skeletons. At this moment, the Hell Courtesan comes to see the impermanence of life and understands who Ikkyū is, and from that day on wears an over kimono with images of Hell. Under Ikkyū’s tutelage, she repents her sins as a courtesan and achieves enlightenment.

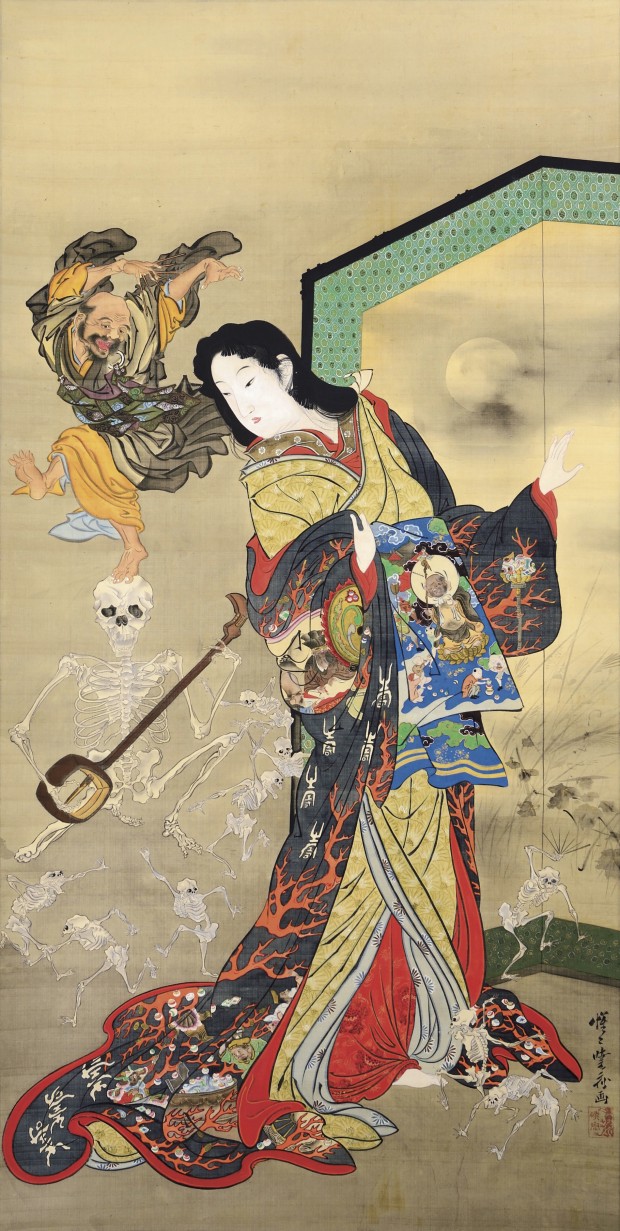

A playful take on the Hell Courtesan

The fantastical elements by Kyōden greatly appealed to audiences and the Hell Courtesan’s popularity continued to grow. This story was illustrated by Utagawa Toyokuni, and his prints served as the inspiration for many other artists such as Kunisada, Hiroshige, Kuniyoshi, and eventually, Kawanabe Kyōsai. In this second painting by Kyōsai, we see the scene from Santō Kyōden’s dramatized rendition—the Hell Courtesan is about to discover Ikkyū and the partying skeletons.

However, you may notice that Kyōsai, a lover of humor, took some liberties with the Hell Courtesan’s outer robes. Upon closer inspection, the typical images of Hell have been transformed into treasures found in Paradise such as gold coins, jewels, and coral. Indeed, the fire-like patterns that adorn her outer kimono are not the flames of Hell, but rather branches of bright red coral. Throughout her robe and on her obi sash are the Seven Lucky Gods doling out fortune and blessings. This playful interpretation by Kawanabe Kyōsai exemplifies how the Hell Courtesan legend continued to evolve over time.

Reference: “Jigoku Dayū and Ikkyū – A Tale About Lively Skeletons” (225-231) by Kazushi Kuroda in “This is Kyosai! The Israel Goldman Collection” published by the Tokyo Shimbun, 2017.

Written by Jennifer Myers.