Flowers above the head of a heavenly maiden

Have you ever heard of the Noh (能) play ‘Hagoromo (羽衣)’? It is based on the legend of Hagoromo (羽衣/robe of heavenly maiden), a well-known folk tale about a heavenly maiden who comes down to earth to play, but hides her robe of feathers from a fisherman and is unable to return to the heavens. Even if you have not seen the Noh play Hagoromo, you may have read Tezuka Osamu (手塚治虫)’s short story ‘Hinotori Hagoromohen (火の鳥・羽衣編)’, which is also based on the legend of Hagoromo.

In the Noh play Hagoromo, a fisherman who accidentally obtains a robe of feathers, at once shrugged off the heavenly maiden’s request to return it. The heavenly maiden is then completely overwhelmed by disappointment,

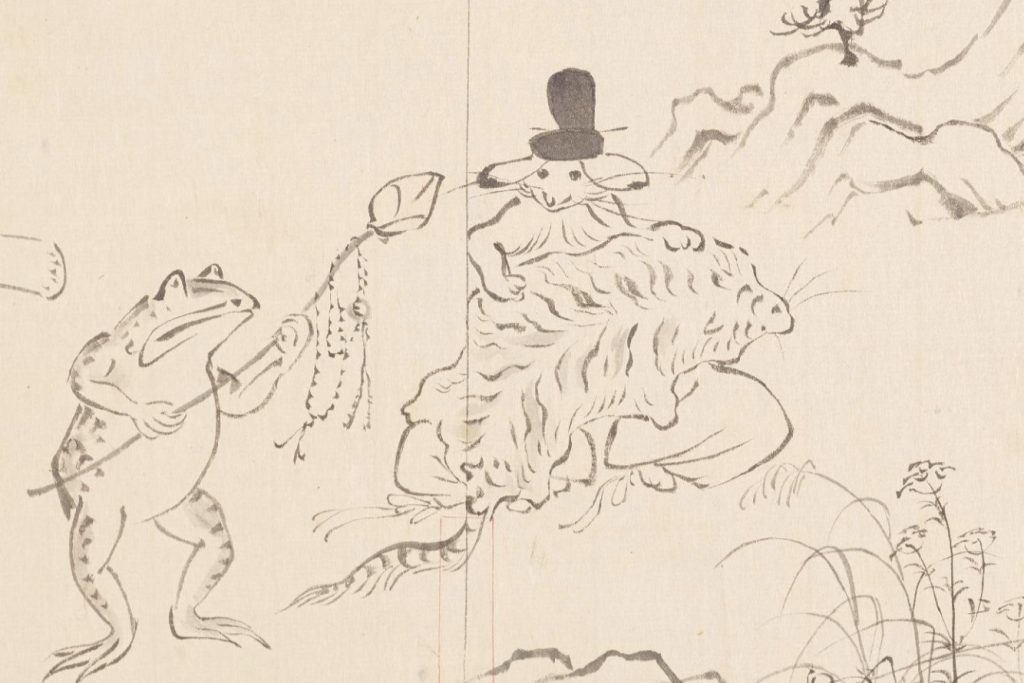

Kazashi no hana mo, shioshio to. Tennin no gosui mo menomae ni miete asamashiya. (挿頭(かざし)の花も、しおしおと。天人の五衰も目の前に見えて浅ましや。)

Translation: Even the flowers on her headpiece are sad. How sad that the five signs of the impending death of a heavenly being, are visible before her eyes.

She appears as if she is about to die. Kazashi no hana (the flowers of the head) is an expression that is difficult to understand today, but here it means the decorative flower that is inserted into the crown.

According to Buddhist teachings, tennin (the Decay of the Angel) have a remarkably long life span compared to humans, but they are still by no means immortal. As they approach death, they show five signs, such as soiling of their clothes and sweating under their arms. These are collectively referred to as the ‘tennin no gosui(天人の五衰)’, and it includes the flowers on their heads beginning to wilt and fade.

The fisherman in the Noh play hagoromo, must have realised that if he did not comply, the heavenly maiden would die. The fisherman retracts his previous statement and returns the hagoromo to the heavenly maiden. The scene in which the delighted heavenly maiden returns to heaven wearing the hagoromo and dancing is the main highlight of this Noh play.

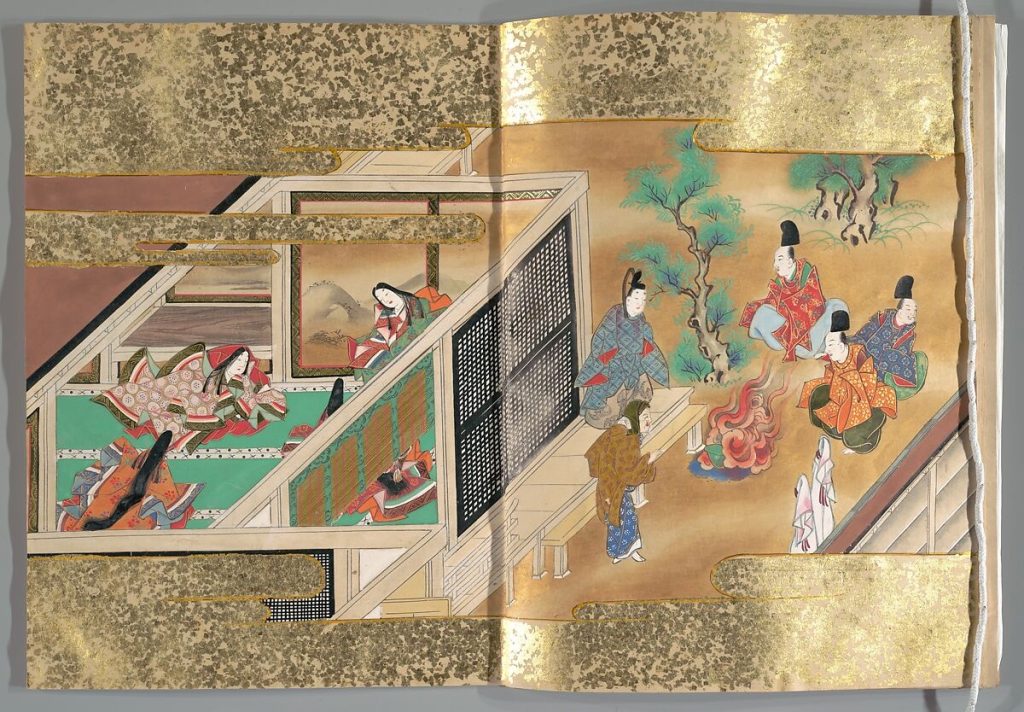

The crowns of the Heian aristocrats show

It is interesting to note that not only the body is stained with sweat and grime, but even the flowers on the head are considered a barometer of a heavenly being’s vitality. In fact, aristocrats in the Heian period sometimes decorated their heads with flowers to indicate their status and position in society, just like heavenly beings. This is what is known as ‘kazashi no hana’ in aristocratic society. Did you know that in the historical drama series ‘Hikaru Kimi e (光る君へ)’, Fujiwara Michinaga (藤原道長) and other aristocrats sometimes put flowers on their crowns during ceremonies and other occasions? The historical term for these flowers is called ‘kazashi’.

However, this kazashi could not be decorated with anything anywhere. The place for decoration is at the base of the crown, where it is slightly raised. Flowers were inserted into the part of the cord known as the age-o. Fresh and artificial flowers were used according to the season, while what should be displayed was strictly regulated according to status.

According to the Heian-period ceremonial book Seikyu-ki (西宮記), for example, when serving as an emissary at a festival, ministers were decorated with wisteria flowers, nagonists with cherry blossoms and councillors with wildflowers. Depending on the position, detailed instructions were sometimes added, such as placing the flowers on the left or right side of the crown, so that a person’s position could be determined by the type and location of the flower arrangement. In other words, the headpiece was not just a decoration, but a barometer and a ceremonial tool that clearly indicated the hierarchy of aristocratic society.

Therefore, it was customary for the emperor or the relevant government office to bestow the head of the family with a gift, rather than for each individual to provide his or her own. However, even the nobility of the Heian period were, after all, human beings just like us today. It is said that sometimes there were people who were unable to receive these gifts without any issues.

In the Kojidan (古事談), a collection of stories compiled in the early Kamakura period, there is an episode in the reign of Emperor Ichijo (一条) in which a nobleman named Fujiwara no Sanekata (藤原実方 was late for a rehearsal of a certain ceremony to be held in the inner palace and was unable to receive the flowers. Emperor Ichijo was the husband of Fujiwara Michinaga’s daughter, Akiko (彰子), so this was indeed a story from the era of the ‘Hikaru kimi he’.

According to various records from this period, Fujiwara Sanetaka was an elegant man who excelled at mai (舞; dancing) and waka (和歌) poetry. He compared his own burning love to the moxa(mugwort) used in moxibustion.

Kakutodani ehaya ibuki no sashimogusa sashimo shirajina moyuru omohi wo

(かくとだに えやは伊吹の さしも草 さしも知らじな 燃ゆる思ひを)

Translation: I would like to tell you at least that I adore you so much, but I cannot. I may not be the moxa(mugwort*) growing on Mount Ibuki, but my adoration for you is that strong. But you do not know of my burning desire.

*mugwort herbs are traditionally used for moxibustion, and therefore is used to emphasise their ‘burning’ desire.

This poem was later selected by Fujiwara no Teika (藤原定家) as one of the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu (小倉百人一首 Ogura Anthology of One Hundred Tanka‐poems by One Hundred Poets).

But no matter who it was, to be the only one not wearing a headdress would have stood out. It’s like when I was a child and I forgot my gym clothes and was made to attend PE class in my own clothes. The nobles around me would probably have whispered to each other, ‘Looks like he came late’ with Sanekata at their side.

Era of the Era of the Last Succession

Unlike me, however, this Sanekata was apparently not an ordinary person who would be upset by the eyes of those around him. He had joined the rehearsal of the ceremony without flowers, but on the way there he approached a kuretake (呉竹) plant in the inner garden, took a branch from it and decorated his crown with it instead of a flower for his headdress. It was so graceful that from then on, the branch of the kure-hana, instead of a flower, was used as the headpiece for the ceremonial rehearsal – so the ‘Kojidan’ (古事談 Reflections on Ancient Matters) says.

To be honest, this episode may seem too good to be true. However, in “Makuranosoushi,” Sei Shonagon wrote an anecdote that shows Sanekata was a man with a very sharp eye. On a certain ritual occasion, Sanekata noticed that a woman’s robe was untied, and not only did he quickly tie it back on, but he also made the woman’s robe a little more comfortable and read the following poem.

Ashibiki no yamai no mizu ha koreru wo ikanaru himo no tokuru naruramu (あしびきの 山井の水は 凍れるを いかなる 紐のとくるなるらむ)

Translation: The water of the mountain wells is frozen at this time of year, but what kind of string could it be that would thaw?

Here, he has used the string as a metaphor for ice. If Sanekata was such a quick witted and slick man, it seems likely that he would have been able to turn his tardiness into praise, but what do you think?

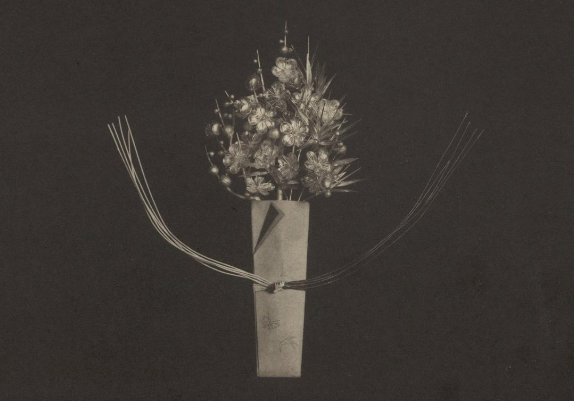

The tradition of bestowing Kazashi continued at court long after the transition from the aristocratic to the warrior class. The fact that silver Kazashi (挿華) are given as souvenirs to participants in the accession ceremonies of modern and contemporary emperors is the result of this tradition being transformed. Four years ago, at the Daijosai and Daikyonogi (大嘗祭・大饗の儀) Ceremony that accompanied the accession to the Throne, sterling silver kazashi in the shapes of bamboo and plum trees were handed out to those in attendance. Incidentally, at the Taisho coronation ceremony, the flowers were in the form of cherry blossoms and tachibana (橘), and at the Showa and Heisei ceremonies, they were in the form of plum blossoms and bamboos.

In the documents published by the Imperial Household Agency on the Daikyonogi, the character for ‘挿華’ is written with the word ‘Kazashi (かざし)’. It is very interesting to note that although times have changed and social conditions have changed, the decorative traditions of the Heian period are still alive today.

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/238049/