The year-end has come around quickly, hasn’t it? Do you all eat toshikoshi soba (年越しそば; Bringing in the new year soba)? This tradition has been part of popular food culture since the Edo period, with various names like ‘toshitori soba (歳取りそば, aging soba)’, ‘omisoka soba (大晦日そば, new year’s eve soba)’, and ‘un soba (運そば, fortune Soba)’. In fact, toshikoshi soba carries different meanings and wishes for the new year! I’d like to introduce a few of these fascinating origins today.

Wishing for longevity

This was the first thing that came to mind for me! Because soba noodles are long, they’re eaten with the hope for ‘longevity and good health’ or that one’s ‘fortune and prosperity will continue to grow.’

Pledging to try again with fierce resolve

‘Kendochorai wo kisu (捲土重来を期す)’ means ‘a person who has failed once is determined to try again with fierce resolve.’ This phrase is also tied to the growth cycle of buckwheat (soba): even after being battered by wind and rain, the crop soon springs back up once exposed to sunlight again. Thus, soba has become associated with ‘health’ and a wish for a better year ahead.

In Edo, a disease called ‘Edo-wazurai (江戸患い; beriberi) was prevalent, and a rumour circulated that eating soba helped prevent it. In fact, soba is rich in vitamin B1, known to help prevent beriberi, and contains a well-balanced array of proteins. These qualities likely contributed to soba’s popularity as both a health food and a symbol of resilience and new beginnings.

Severing away misfortunes

Despite being long, soba noodles are more prone to breaking than udon or somen, which led to the custom of eating them with the wish to ‘severing off the year’s misfortunes.’ In fact, it was even believed to sever financial debts, which is why it was sometimes called ‘shakkin giri (借金切り; debt-cutting noodles)’ or ‘kanjo soba (勘定そば; account-settling soba).’ As part of the tradition, one had to finish every bite, leaving no noodles behind, to make sure nothing of the old year’s misfortunes would carry over.

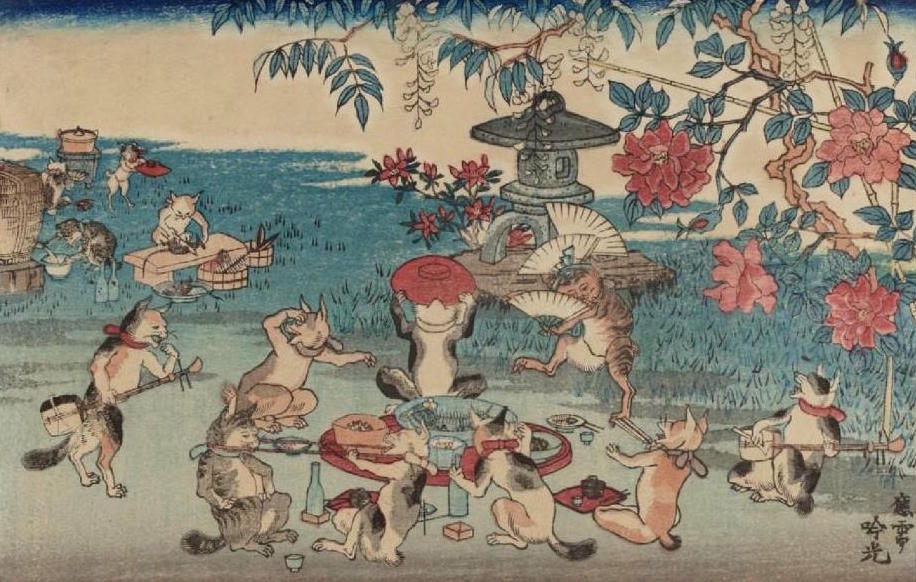

To attract wealth and enhance one’s luck

Goldsmiths and silversmiths used soba flour to gather scattered gold dust and to stretch gold leaf, which is believed to have led to soba being eaten as a good luck food for ‘collecting money’ and ‘stretching wealth.’ Additionally, there is a theory that during the Kamakura period, at Joten-ji (承天寺) Temple in Hakata, soba mochi was offered to townspeople who who were struggling to make ends meet, referred to as ‘yonaoshi soba (世直しそば; soba for restoring prosperity).’ The following year, as everyone began to experience good fortune, they started eating soba on New Year’s Eve, calling it “un soba (運そば; luck soba).’

There seem to be many different theories surrounding ‘Toshikoshi Soba.’ What kind of wishes will you make when you eat it this year as you prepare for the new year?

References

Soba no jiten (蕎麦の辞典), Niijima Shigeru (新島繁), Kodansha (講談社), 2011

Nihonjin no「shoku」, sonochie to shikitari naze, kireyasui toshikoshisoba ga choju no shocho nanoka (日本人の「食」、その知恵としきたり なぜ、切れやすい年越しそばが長寿の象徴なのか), Nagayama Hisao (永山久夫), Kairyusha (海竜社), 2014

E de miru edo no shokugoyomi (絵でみる江戸の食ごよみ), Nagayama Hisao, Kosai-do (廣済堂), 2014

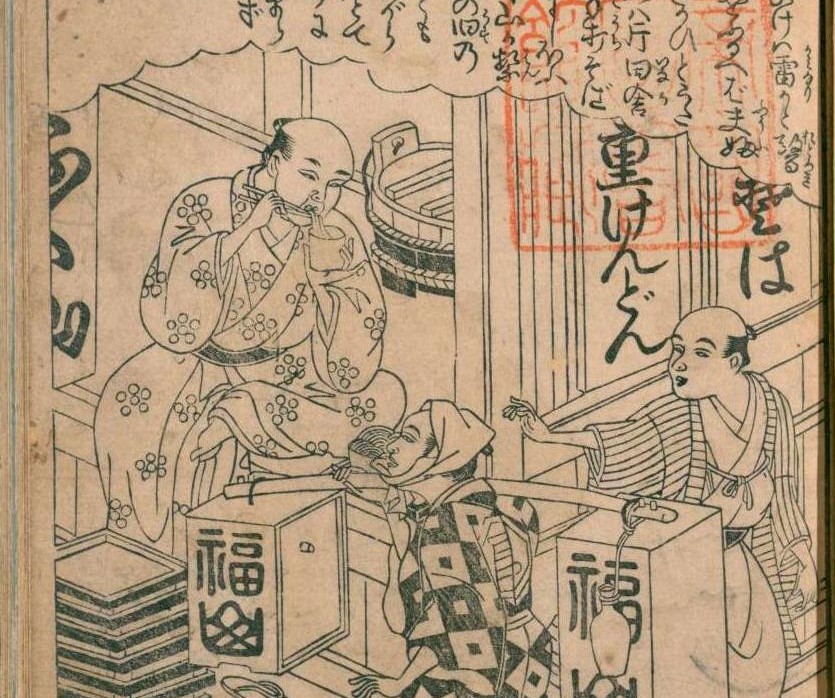

Eyecatch Image: Ehon Yachiyo-gusa Vol. 3 (絵本八千代草 3巻), by Suzuki Harunobu (鈴木春信), Yamazaki Kinbei (山崎金兵衛), Meiwa (明和) 5. National Diet Library Digital Collection https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/2533267

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/rock/culture-rock/232604/