Ancient people skilled in the handling of leather

Historical novelist Sugimoto Sonoko (杉本苑子), whose stories span a wide range of worlds from the Asuka period to the Meiji era, has a short story called ‘Keman (華鬘)’. It takes place immediately after the Taika (大化) Reformation. The story begins with a scene in which a woman, who later becomes the wife of Emperor Tenchi (天智), receives a cowhide keman (buddhist ritual decoration 華鬘) from her father.

Keman is a type of buddhist ritual decoration with openwork carving, which is still displayed in temples today. While most are made of metal, the keman in the story is made of dyed deerskin and is very light. The main female character gets into unexpected trouble when she tries to decorate her room with these.

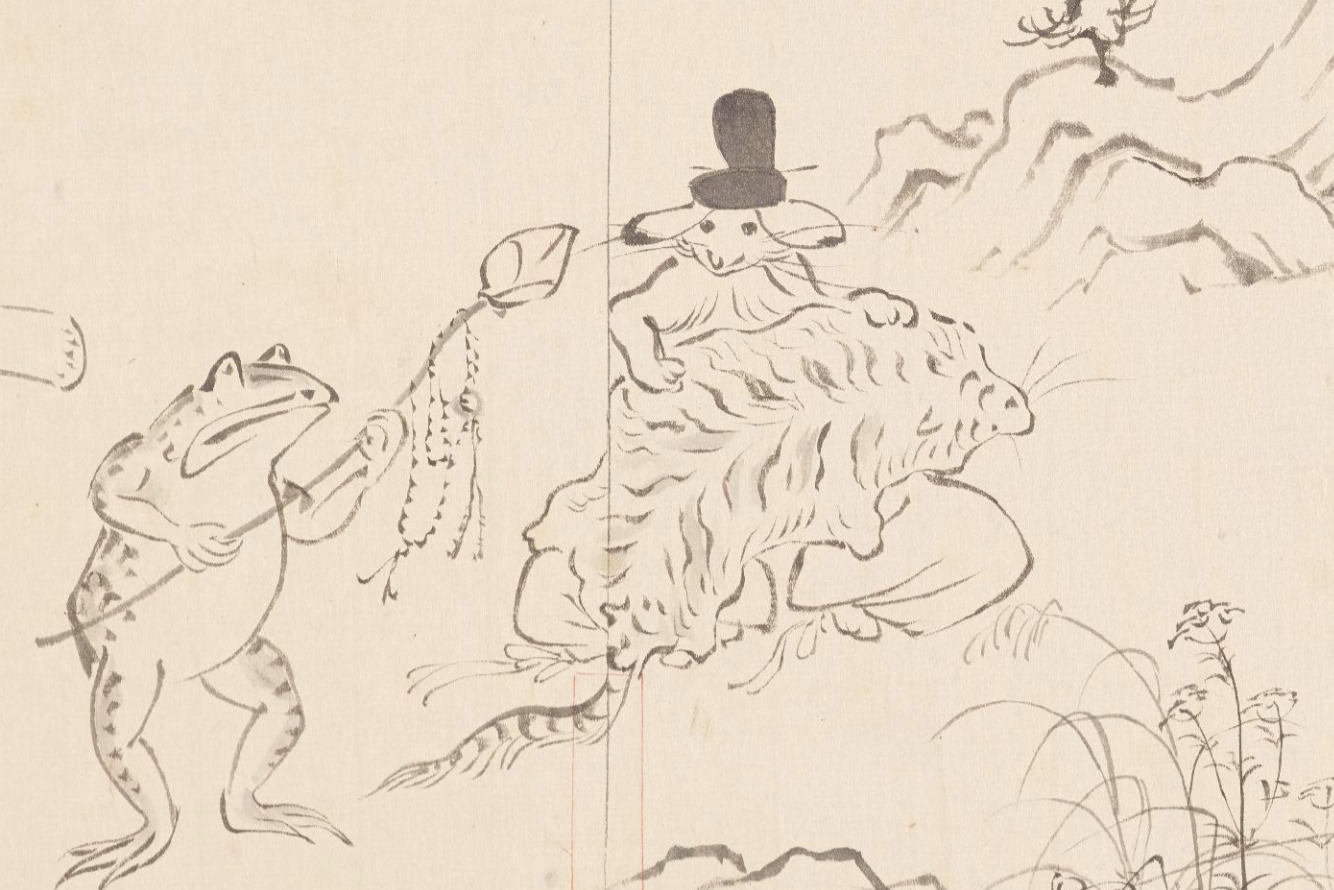

Although there are no actual examples of leather Keman from the Asuka (飛鳥) period, there is currently a cowhide keman from the mid-Heian period in the collection of the Nara National Museum. This item is designated as a national treasure. It is made of lacquered leather, processed through and through, and colourfully painted with floral patterns and ‘Karyobinga (迦陵頻伽)’, a bird with a human face that is believed to dwell in the Paradise, and other floral patterns.

Leather is light and well preserved, so it is said to have already been used for armour and other items since the Kofun period. The ‘Nihon Shoki (日本書紀)’, a history book compiled in the 7th century, tells of an incident when Amaterasu Omikami (天照大御神) became angry at the behaviour of his brother Susano no Mikoto (須佐之男命) and retreated to the Amanoiwaya (天石窟), where a leather blower called the Ame no Habuki (天羽鞴) was made as a means of luring Amaterasu Omikami away. Of course, this is not true, but the description that it was made from the skin of a whole Mana Deer (真名鹿) is quite detailed, and it can be imagined that people at that time used leather on a daily basis.

The ‘Yoro ritsuryo (養老律令)’, promulgated in the eighth century, is an important historical document for understanding the national system of the time. One of its volumes, the ‘Clothing Ordinance’, stipulates the clothing to be worn by emperors and nobles, and various types of leather footwear appear. For example, footwear used by the imperial family and nobility for ceremonial occasions is made of black leather and has thick soles. Women’s footwear is green leather shoes. It is interesting to note that everyday footwear is distinguished as leather shoes with only one sole, not a thick sole.

The Shosoin (正倉院) Repository now preserves a pair of leather shoes called ‘nouno gorairi (衲御礼履)’, said to have been worn by Emperor Shomu (聖武) on the occasion of the opening of the Great Buddha at Todaiji Temple. Far from today’s image of leather shoes, these shoes are dyed a vivid deep red, and the flower-shaped metal fittings with glass and pearls scattered throughout accentuate the glamour of the shoes. The surface is suede calfskin, the inside is smooth white leather with a twill insole, and the toe part is decorated with cut-out white leather.

There are many examples of the use of leatherwork for decoration in the Shosoin, such as the ‘murasakigawasaimon shugyokukazari shishuranobi (紫皮裁文珠玉飾刺繍羅帯)’ (fragment), a sash decorated with flower-shaped embroidery and purple-dyed leather. It is decorated with glass, crystal and pearl ornaments and is one of the most beautiful of the Shosoin obis. Here, the purple-dyed leather is cut into the shape of a plant called suikazura (忍冬), and its eight-centimetre width gives it a presence as strong as that of jewellery.

Although this is a slightly later document, the ‘Engishiki (延喜式)’, compiled in the early Heian period, states that leather such as purple leather, scarlet leather and yuhata-gawa (纈革) leather were brought to the capital from Dazaifu (大宰府) in Kyushu. The purple and scarlet leathers were dyed leathers, as we have already seen, and the valerian leather was probably tie-dyed leather. Cowhide leather itself was also delivered from Owari (尾張, present-day Aichi Prefecture), Omi (近江, Shiga Prefecture) and other regions, but the reason why dyed leather is clearly differentiated from the others is no doubt because the former was used for leather products such as harnesses, while the latter was used for leather products as craftwork such as ornaments.

As previously mentioned, the Shosoin also contains jade belts with buckles exactly the same as today’s belts, and some of these belts are made of leather. This is precisely the same material and shape as today’s leather belts. However, for example, the ‘kongyoku no obi (special navy blue obi used in ceremonious court dress)’ with its beautiful navy blue square and rectangular beads was once thought to be made of cowhide, but recent research has suggested that it was not cow or horsehide, but leather of some other small animal. The use of smooth calfskin for the nouno gorairi (ceremonial shoes) suggests that the ancient people were more skilled in the handling of leather than we might imagine.

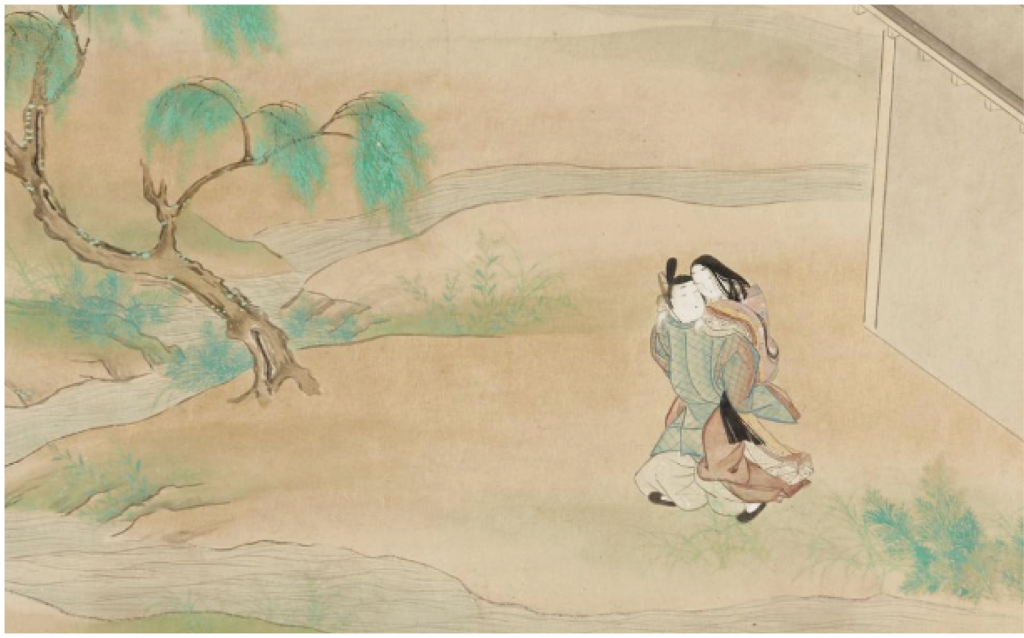

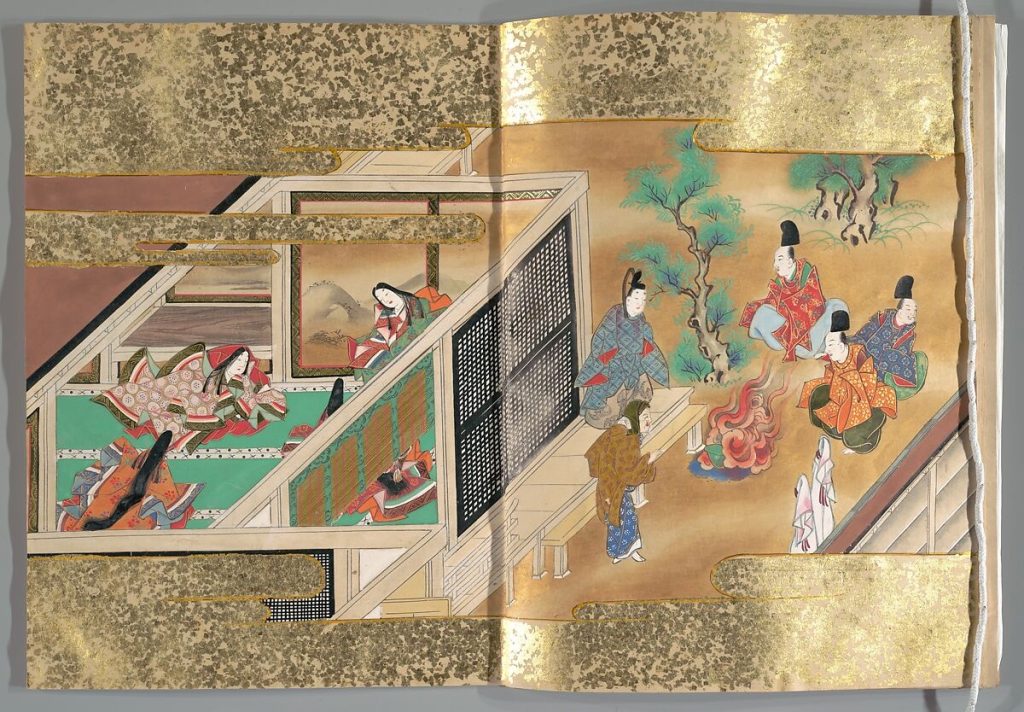

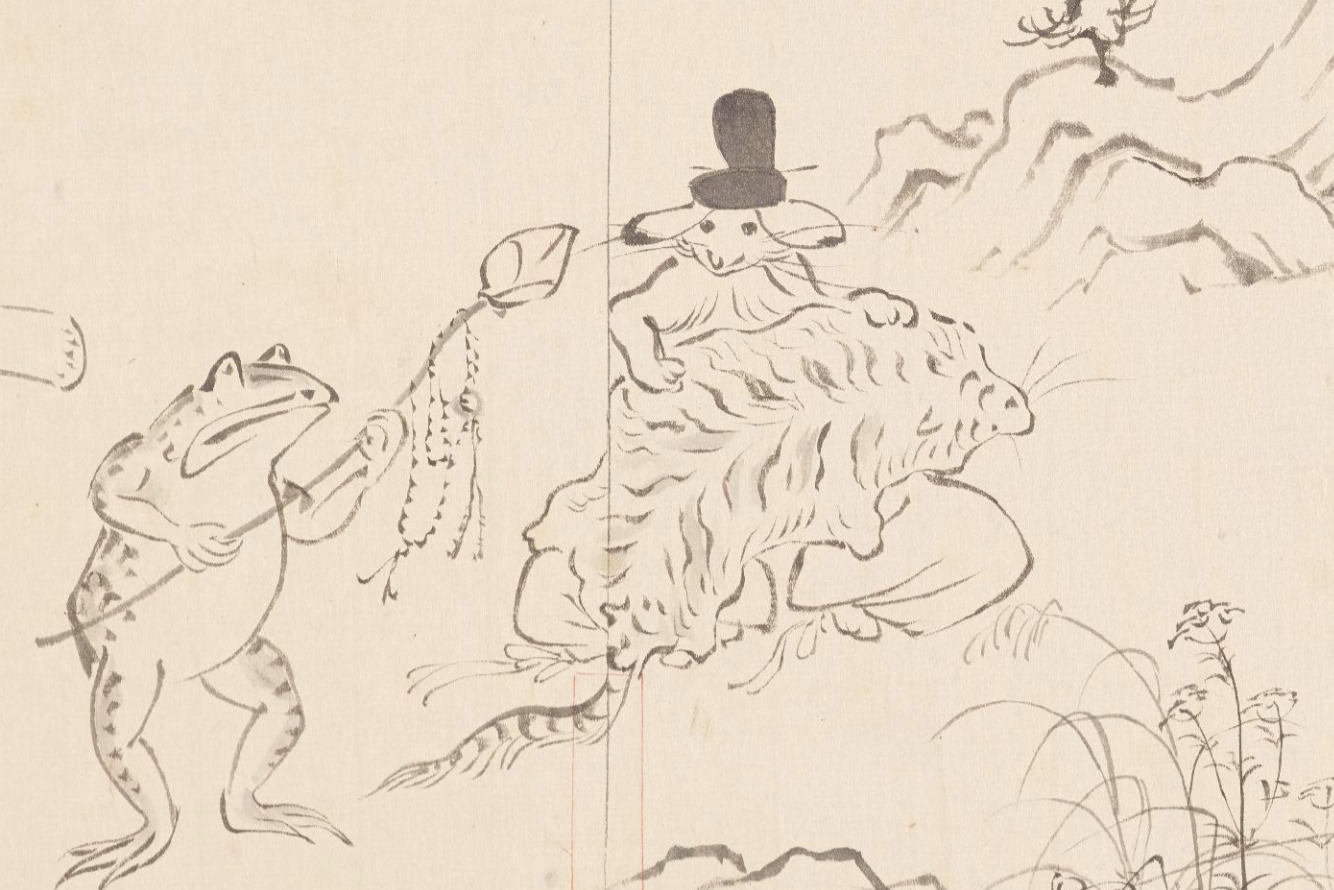

The important thing is how one reflects after a killing

By the way, there is a temple known as Kodo (革堂) in present-day Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto, not far from the Kyoto Gyoen Garden. Its official name is Reiyuzan Gyogan-ji Temple (霊麀山行願寺), a Tendai (天台宗) sect temple built by a monk named Gyoen (行円) in 1004, at the time Murasaki Shikibu, the main character in the historical drama ‘Hikaru kimihe (光る君へ)’, was writing The Tale of Genji. According to one theory, Gyoen was originally a hunter from the west of Japan. When he killed a doe, a fawn came out of its belly, and he repented of his deed and became an ordained priest. He was so determined not to forget his deed that he always wore the skin of the mother deer he had killed, which earned him the nickname ‘Kawahijiri (革聖)’, and the temple he opened was also given the sobriquet ‘Kodo (革堂)’.

In a dictionary compiled in the mid-Heian period, called ‘Wamyoruijusho (倭名類聚抄)’, leather and hides are strictly distinguished. As in today’s usage, skin is fur with the hair still attached, while leather is tsukurikawa (都久利加波), i.e. processed hair and fat have been removed.

Gyoen’s folklore appears in a mixture of leather and leather, and it is not clear from the historical record alone which of the two he wore. Currently, an item believed to be Gyoen’s deer robe is housed in the Reihokan (霊宝館) of the Leather Hall and is open to the public only a few days a year, but from what is confirmed, it appears that Gyoen was wearing fur rather than leather.

Incidentally, there are other examples of monks wearing objects derived from dead animals. Kuya Shonin (空也上人), the founder of Rokuharamitsu-ji Temple (六波羅蜜寺), who is well known for his unique portrait sculptures of six Buddhas protruding from his mouth, is one such example. Kuya had a deer that he loved very much, but one day a samurai killed it. Kuya received the deer’s skin and antlers from him, which he made into a robe and put the antlers on the tip of his staff, and walked around chanting the Buddhist prayer.

Today, in some manners, fur and leather goods should not be used for weddings because they are associated with killing. However, the deeds of Gyoen and Kuya teach us that what is important is not the behaviour of whether or not one wears items of animal origin, but the mind that remembers the thought of killing. I shudder at my own contradiction of dressing myself in a way that avoids fur and leather and tucking into Wagyu beef steak at the wedding reception.

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/232363/