Artists who assert that they are ‘cartoonists’

In 1993, The British Museum in London held the first exhibition of Takeda’s work in a Western museum, called ”Takeda Hideo (武田秀雄) and the Japanese Cartoon Tradition”. Now thirty years later, Takeda’s works are exhibited in Denmark for the first time, and he has been positively received.

Takeda Hideo was born in 1948 in Osaka and studied sculpture at the prestigious Tama Art University, Tokyo, but already started working with graphic art and had his first collections of cartoons published in the 1970s under the titles Madame Chang’s Chinese Restaurant (1973) and Yogi (1974).

I first had the pleasure of meeting Takeda the first time in the Autumn of 2022 when he kindly accepted a visit to his house in Osaka, where he lives and works. I came to interview him for a book on modern Japanese prints. On my second visit last October, I was there to borrow works for an exhibition I was curating in Denmark.

Throughout his artistic career, Takeda has worked with many different media, such as sculpture, painting, drawing and printmaking. But Takeda does not consider himself an artist. He is a cartoonist, he says. Artist or not, he is a master of lines and patterns – and not least humour.

Takeda’s house is filled to the brim with works of he always comic ’strokes of genius’ and grotesque motifs, which made it a difficult task to decide which prints should go in the exhibition. After going through many piles, I ended up with a beautiful selection of silkscreen prints, which is now on display at the museum in Denmark as part of the exhibition “Skabninger” (‘creatures’): Graphic Art from Japan to Denmark until 31 August 2024 at Vejle Kunstmuseum.

Takeda’s works play an important role in the history of modern Japanese printmaking, and I believe that he deserves more recognition in Europe.

Danish view of ‘yakuza’ culture

The appeal of Takeda Hideo’s work may require some further explanation.

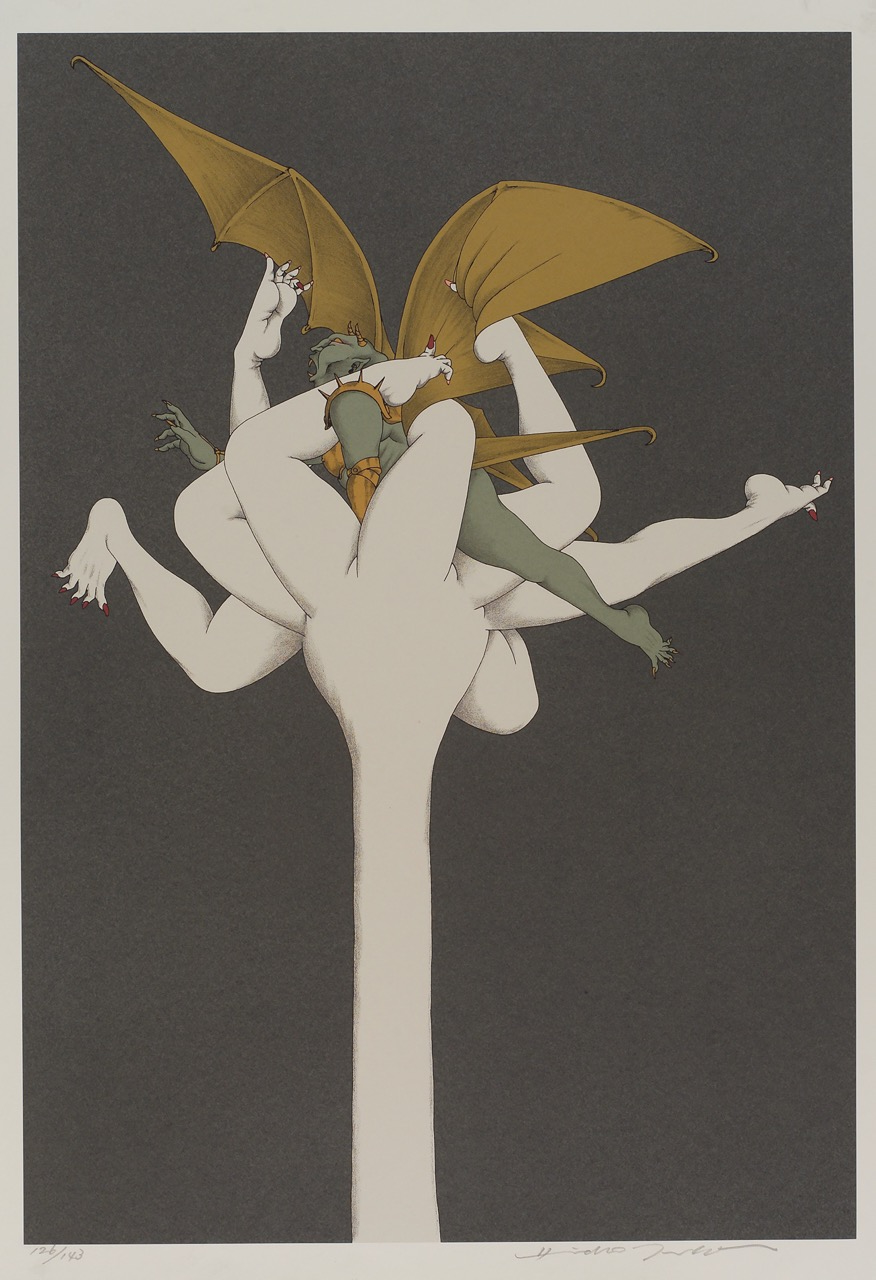

In 1976, Takeda created his first silkscreen prints – works made of clear black lines in combination with bright colours and patterns – and they show his unique sense of humour and incredible talent.

The first series is titled Mon Mon and refers to kurikara monmon (倶利迦羅紋紋), the Japanese tattoo traditionally reserved the yakuza.

In this instance Takeda has taken a traditional Japanese motif and presented it in an absurd-comic dispute, where he has stripped the ‘masculine’ body of clothes and dressed it in full body tattoo and – in this case – women’s panties.

Takeda’s later series Genpei is based on the feud between the two clans Minamoto (Genpei; the whites) and Taira (Heike; the reds) during the Heian period (794-1185). The war lasted from 1180 to 1185 and was the culmination of a decades-long conflict over military power and thus control over Japan. The theme of the Genpei War in medieval Japan between the two clans Taira (Heike) and Minamoto (Genji) has traditionally been a favourite motif among Japanese artists.

In his series, Takeda has continued the tradition but with a modern twist. His warriors wear helmets and weapons from the period but are only adorned with body tattoos and loin cloths, like modern-day yakuza gangsters. On closer inspection, several of them are not riding horses, but rather sitting on women in grotesque poses.

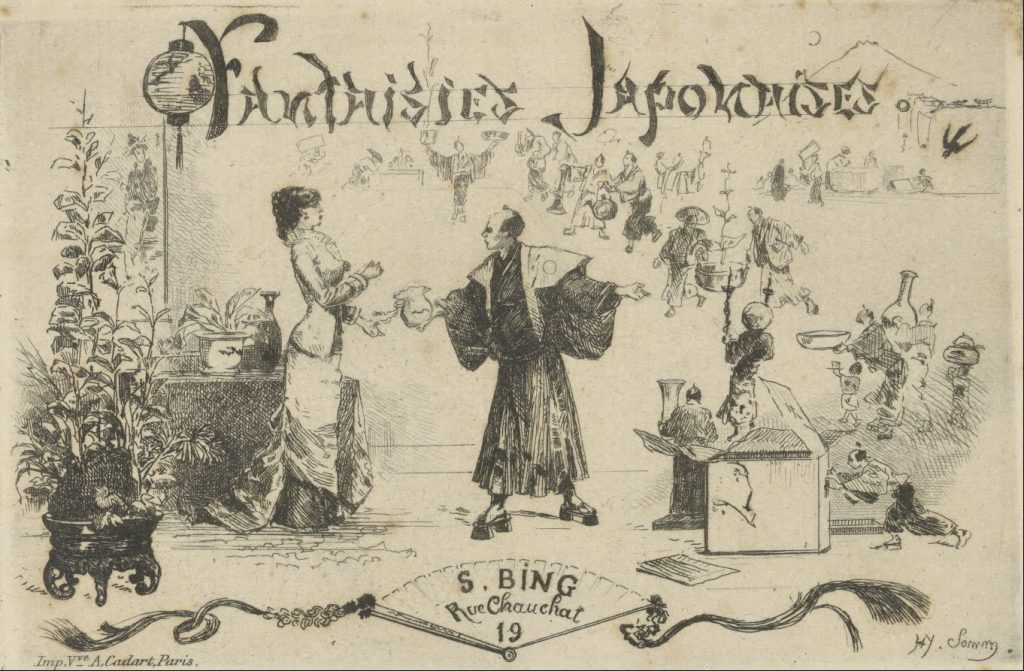

There can be no doubt that the Japanese tradition, technically and in terms of motifs, have left traces in Takeda’s work. His silkscreen prints bear resemblance to the kabuki actors and samurai warriors of the Utagawa School of the 19th century. In several works there are also clear references to the classic wave motif.

Grotesque, eroticism and humour

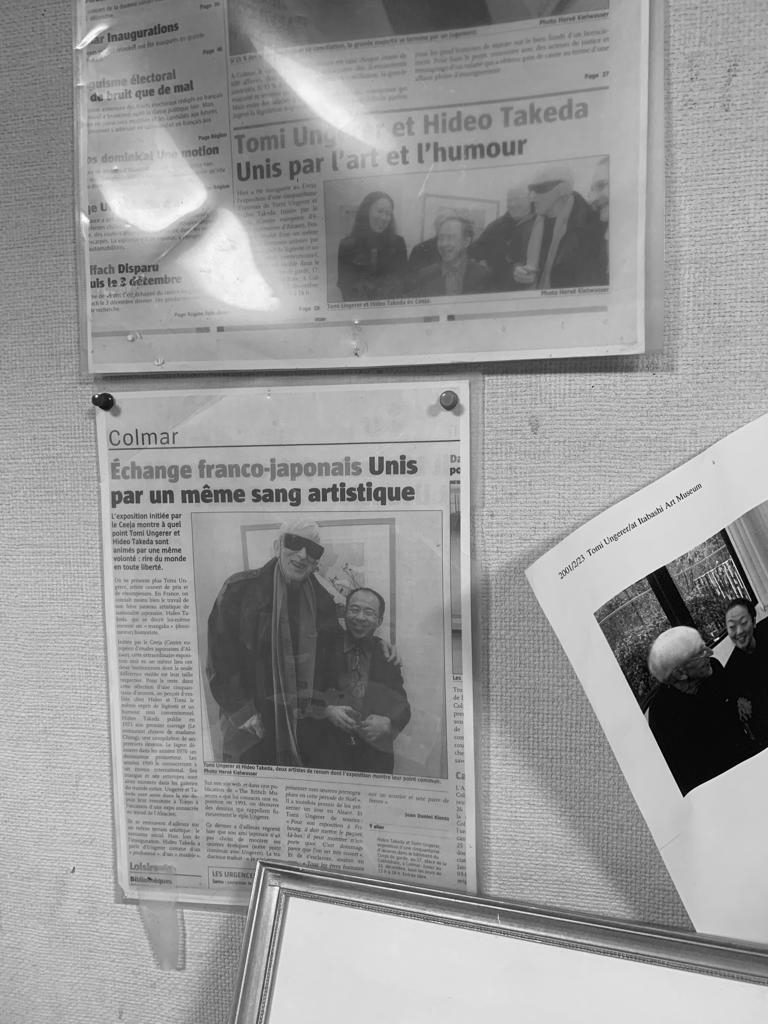

Interestingly, Takeda does not accept his Japanese heritage as a source of influence in his works, instead he mentions cartoonist Ronald Searle (1920-2011) as well as the caricaturist Tomi Ungerer (1931-2019) as inspirations, with whom Takeda had a two-man show in Paris in 2006.

The interplay between the absurd and the humoristic, often combined with brutal eroticism, is characteristic of Takeda who in no way is ‘woke’ at first sight – his works should be taken with a large grain of irony and humoristic distance. This is what makes his works stand out.

The irony and absurdity is also clear in his series Inferno (2000) which depict ‘hell for women’. The sarcastic moral of this series is that if you don’t take good care of your partner, you can end up here.

Again, Takeda works with the contrast between the grotesque, the violent and the pleasurable, build on traditional shunga, while remaining completely original in his expression.

The erotic genre shunga established during the Edo Period (c. 1603-1867) in the form of ukiyo-e prints, books and paintings was a enjoyed by all social classes, depicting many facets of sex and sexuality, often with a humouristic approach.

Most ukiyo-e artists took up shunga throughout their career, such as Kitagawa Utamaro (c. 1753-1806) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), who created one of the most known shunga motifs, “The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife” (also known as “Girl Diver and octopi”), published in 1814 as part of a 3-volume book.

Takeda Hideo’s works were invited from Japan for the current exhibition, the Danish audience who is familiar with the tradition of caricatures seem at once impressed by the beauty, the humour and not least the high quality of the prints. As an artist – which I choose to call him because of his great talent – Takeda has carried a long tradition of Japanese printmaking into the modern era with his prints that stand out as wonderful, entertaining and timeless as ever.

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/236251/