A special thanks to Israel Goldman for allowing the use of images from his Kyosai collection.

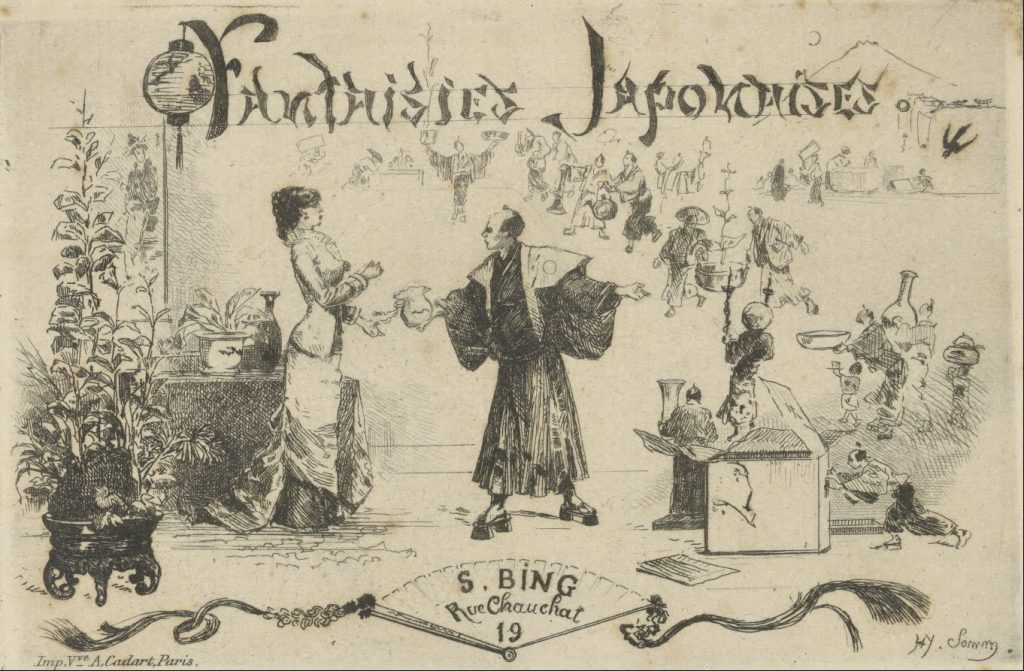

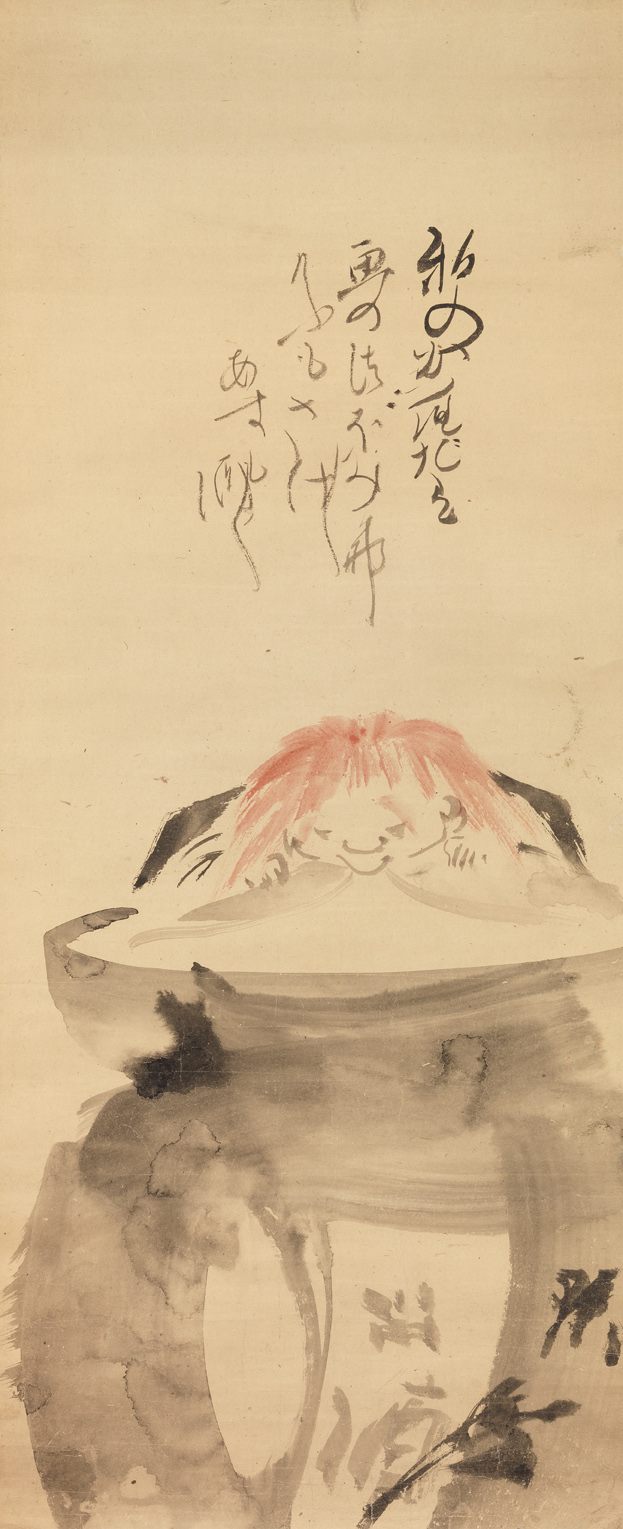

‘The demon of painting’, Kawanabe Kyosai

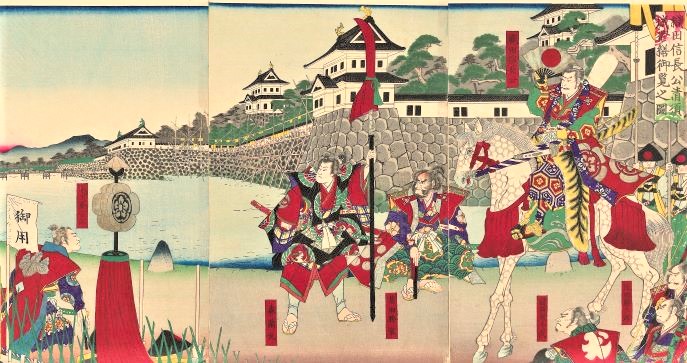

Imagine in the dark of the mild but misty spring night, a pandemonium of demons, ghosts, skeletons and frolicking animals appearing at Zuirin-ji temple cemetery in Yanaka district (located just between Ueno and Nippori stations) gathering around a grave to drink saké in honour of the person buried there: ‘The demon of painting’, Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-1889).

Israel Goldman Collection, London. Photo: Art Research Center, Ritsumeikan University

Kyosai would without a doubt have appreciated such a gesture as he loved to drink, and often did so while painting when creativity would flow along with the saké.

Why Danish curators are looking at Kyosai

Kyosai, perhaps the most fascinating and unique artist of the Meiji period (1867-1912) in the transition from old to new Japan, was a master creator and caricaturist of both the natural and supernatural world: crows, tigers and elephants, demons, frog acrobats, tengu, the seven gods of fortune, ghosts and dancing skeletons, along with the more serious types such as Shoki the demon queller, the King of Hell and the zen patriot Daruma.

Kyosai was drawn to both the humorous and horrible, which followed him from an early age. When Kyosai was just 9, he had come across a severed head of a man in the Kanda River. Although initially shocked, Kyosai pulled it out of the water and brought it home to sketch; an event that understandably left a strong impression on the young boy and one he would return to as a subject later in life.

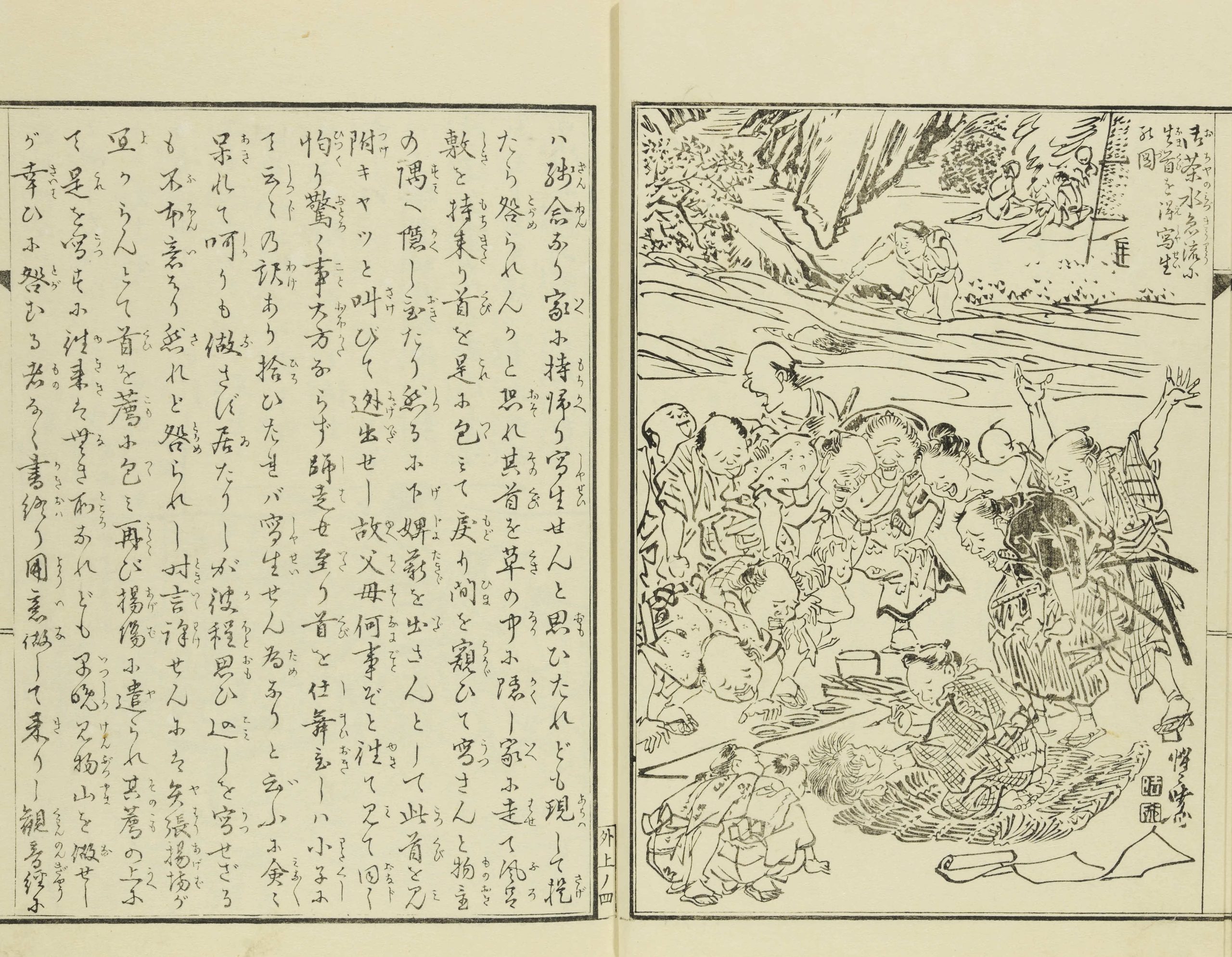

Israel Goldman Collection, London. Photo: Art Research Center, Ritsumeikan University

Kyosai was a very skilful and prolific artist, producing thousands of paintings, prints and drawings during his lifetime. Initially apprenticed as a 7-year-old to none other than ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), who represented the ‘common’ and anti-academic, at the age of 10, Kyosai began to study academic painting as part of the traditional Kano school.

While Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) was – and probably still is – the most recognised Japanese artist in the West, he had passed away by the time Japan opened to visitors from outside. Kyosai on the other hand, was very much alive and accessible, and he met with several of the foreigners living in or visiting Japan during the Meiji period.

Among them was the painter Mortimer Menpes; British surgeon William Anderson, who commissioned works directly from Kyosai (which he sold to the British Museum in 1881 as part of a bigger Japanese art collection); French industrialist and founder of Musée Guimet in Paris, Émile Guimet. The latter visited Kyosai at his home in Tokyo in 1876 during his travels in Asia with the artist Félix Régamy, who even ended up having a draw-off with Kyosai.

Kyosai also contributed with works to several of the world exhibitions held during the second half of the 19th century: Vienna (1873), Philadelphia (1876) and Paris (1878), as well as taking on a westerner as a student.

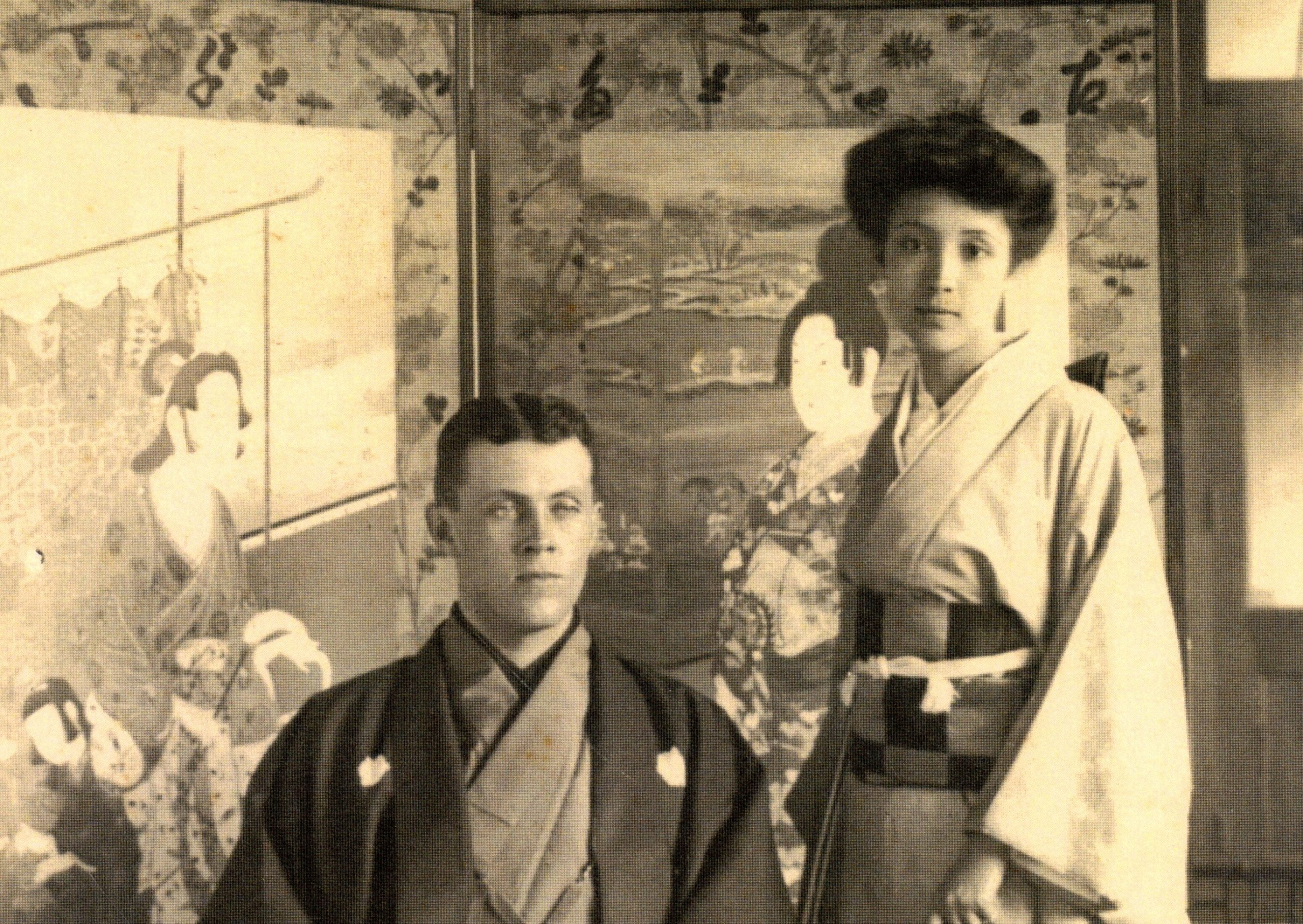

Josiah Conder’s relationship with Kyosai

Josiah Conder (1852-1920), a so-called oyatoi, a foreigner hired by the Japanese government during the Meiji period when everything Western came into fashion, arrived in Japan in 1877 to teach architecture at the Imperial College of Engineering. In this role he would go on to teach many from the first wave of modern Japanese architects.

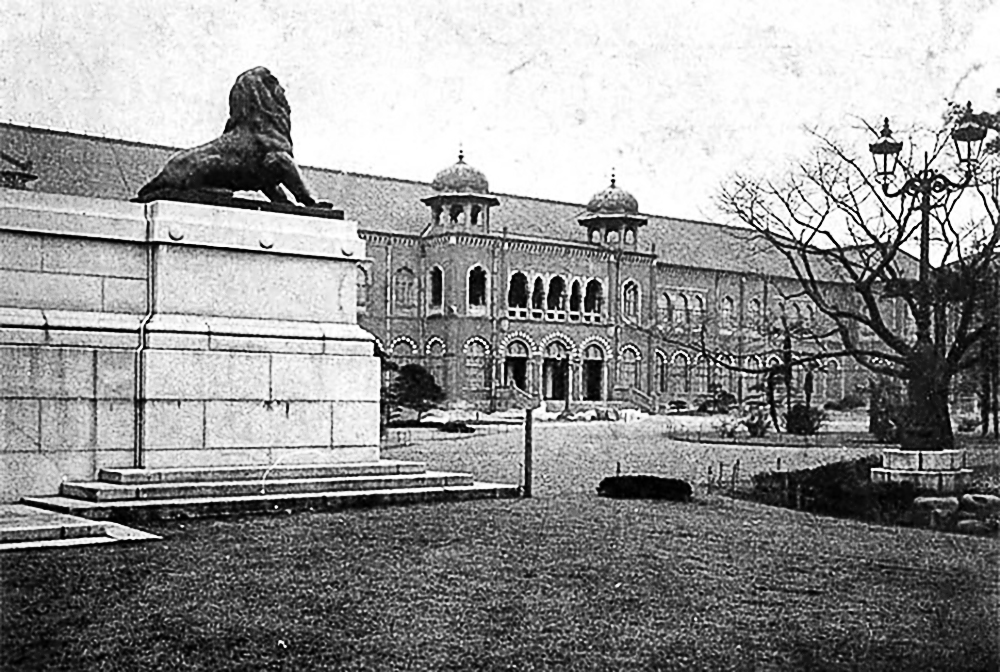

Conder, who is generally acknowledged as the ‘Father of modern Japanese architecture’, was the architect behind over sixty official buildings from the Meiji period, such as Japan’s first National Museum and Rokumeikan (demolished in 1941), the ‘banqueting house’ famous for its elaborate parties where Westerners and high-ranking Japanese would meet and mingle.

Sadly, Conder’s National Museum was destroyed during the Kanto earthquake in 1923, but in 1881 it was the setting for the second Domestic Industrial Exhibition, where Kyosai participated and won the highest prize for a painting depicting a winter crow. It was likely here that Conder and Kyosai first met each other.

After many requests, Kyosai finally accepted to take on Conder as his student, whom he later gave the name Kyoei.

As their relationship grew, Conder would become not only a student but also a close friend and patron with many of Kyosai’s works ending up in Conder’s collection, which Conder’s daughter Helen Aiko (1883-1974) inherited.

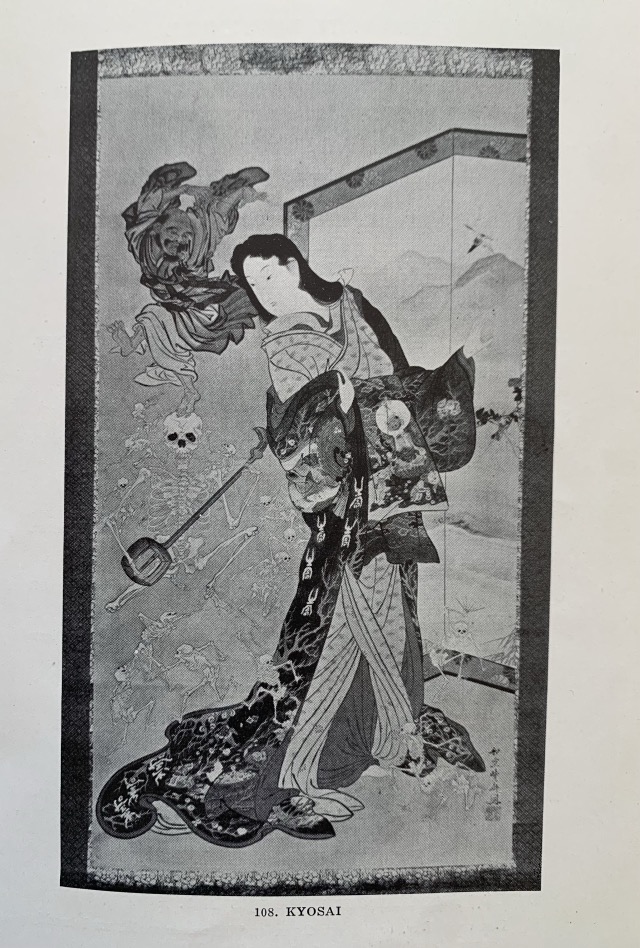

Conder’s daughter, Aiko, moves to Denmark

When Helen Aiko moved to Denmark with her children and husband, the Swedish Consul General William Lennart Grut (1881-1949) whom she had married in 1906 in Tokyo, a big part of this collection naturally ended up there. In June 1942, a sale of more than 375 lots from the collection took place at the then leading Danish auction house Winkel og Magnussen. Including in the sale was Kyosai’s famous painting of the Hell Courtesan (Jingoku dayu) painted after 1885, of which there are three versions, as well as Shoki and Two Demons from 1882.

Conder attending on Kyosai’s death

Having received training from the two opposing schools, Kyosai’s works clearly reflect influences from both traditional Japanese art as well as popular culture. As an artist, he manifests a versatility, not only in technique, but in the choice of subjects balancing between the old and new during a time which saw Japan transform from a feudal society under military rule to a modernised nation adopting Western political, financial and military systems.

When Kyosai passed away on 26 April 1889, Conder was by his bedside.

Conder would go on to write one of the most important sources on Kyosai’s life and work: Paintings and Studies by Kyosai published in 1911.

This article is an original text of https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/243631/