Free admission and extensive exhibits: a treat for sumo fans

The Sumo Museum is located within the Ryogoku Kokugikan. Situated on the far right side of the main hall, it organises exhibits to coincide with the three main tournaments held in Tokyo (January, May, and September). While a ticket is required during the 15 days of the Grand Sumo Tournament, entry on all other open days is surprisingly free.

In a world where costs of living are rising, this is a rare opportunity to enjoy a fascinating exhibit without charge. Despite being free, the museum ensures its displays are never repetitive, consistently offering engaging and interesting special exhibitions that captivate sumo enthusiasts.

Nakamura Fumihiko (中村史彦), a curator at the Sumo Museum and manager of the Japan Sumo Association’s archival management and utilisation promotion office, commented: “Although it is a small, single-floor museum, we focus on special exhibitions themed around Grand Sumo, rather than permanent displays. Before the pandemic, we held six exhibitions annually, but we reduced this to three per year to extend the duration of each exhibition, allowing more people to see them.”

Did you know the Sumo Association was also in Osaka? Unravelling history in “100 years of Grand Sumo”

The current special exhibition at the Sumo Museum is 100 Years of Grand Sumo (exhibition period: 11 May to 22 August 2025). This exhibition commemorates the 100th anniversary of the foundation’s establishment, looking back at its history and focusing on the achievements of famous wrestlers, the evolution of sumo culture, and the history of the Kokugikan.

Mr. Nakamura, who curated the milestone exhibition 100 Years of Grand Sumo, highlighted some of the key attractions:

“One hundred years ago was Taisho 14 (1925). In that very year, the Emperor’s Cup was created using a donation received for the regent’s (Emperor Showa) observation of a sumo match. This served as a catalyst for the Tokyo and Osaka Sumo Associations, which had previously operated separately, to begin efforts to merge.

I highly recommend seeing the replica of the Emperor’s Cup (awarded to the winner of the Grand Sumo Tournament) made around that time, as well as the sumo rankings prepared during the merger process between Osaka and Tokyo. The rankings reveal that Tokyo had more wrestlers and superior strength compared to Osaka. Furthermore, the exhibition showcases how sumo and wrestlers evolved during wartime, post-war overseas tours, and the relationship between sumo and the Olympics. I believe even those unfamiliar with sumo will find it enjoyable.”

The exhibition features yokozuna ropes—the thick ropes worn around the waist for the ring-entering ceremony—from previous eras, specifically the Unryu (雲龍) style and Shiranui (不知火) style. Visitors can observe that these ropes are notably smaller than those used today, illustrating how the wrestlers’ physiques have grown over the past 100 years.

“Displaying objects and equipment allows us to make interesting comparisons between past and present,” Mr. Nakamura noted. “Until 2004, smoking was allowed in the masuseki (枡席, box seats). Consequently, hibako (火箱, fire boxes) and ashtrays were provided in the boxes. We display these items to convey the atmosphere of sumo viewing during that period.”

Mr. Nakamura admitted that curating the 100th-anniversary exhibition in the small space presented challenges in balancing comprehensive content with ease of viewing. “Also, not limited to this exhibition, it’s always difficult to create a structure that engages everyone, from sumo novices to kokakuka (好角家, die-hard sumo fans). That’s why it makes me happy when people say, ‘It was fascinating’ or ‘It brought back memories,’ and especially when young visitors and foreigners share photos of the exhibits on social media as enjoyable memories.”

The first director, the ‘Lord of Sumo,’ was a major collector of sumo materials

The Sumo Museum was established in 1954. After the Kokugikan was destroyed by air raids during World War II, it was relocated from Ryogoku to Kuramae (蔵前). The museum was founded concurrently with the opening of the Kuramae Kokugikan.

The first director chosen was Sakai Tadamasa (酒井忠正), who also served as the inaugural chairman of the Yokozuna Deliberation Council. Born in 1893 as the second son of Count Abe Masatsune (阿部正恒), the lord of Bingo Fukuyama Domain (備後福山藩), Sakai married the daughter of Sakai Tadaoki (酒井忠興), the head of the Himeji Domain lord’s family, and became his adopted son-in-law. He served as a member of the House of Peers and held the position of Minister of Agriculture and Forestry.

Sakai, who would have been a feudal lord in a different era, was such a devoted sumo fan that he was nicknamed the ‘Lord of Sumo.’ He collected sumo-related items from a young age, and the Sumo Museum was established with the purpose of researching and displaying his collection, which amounted to over 10,000 items.

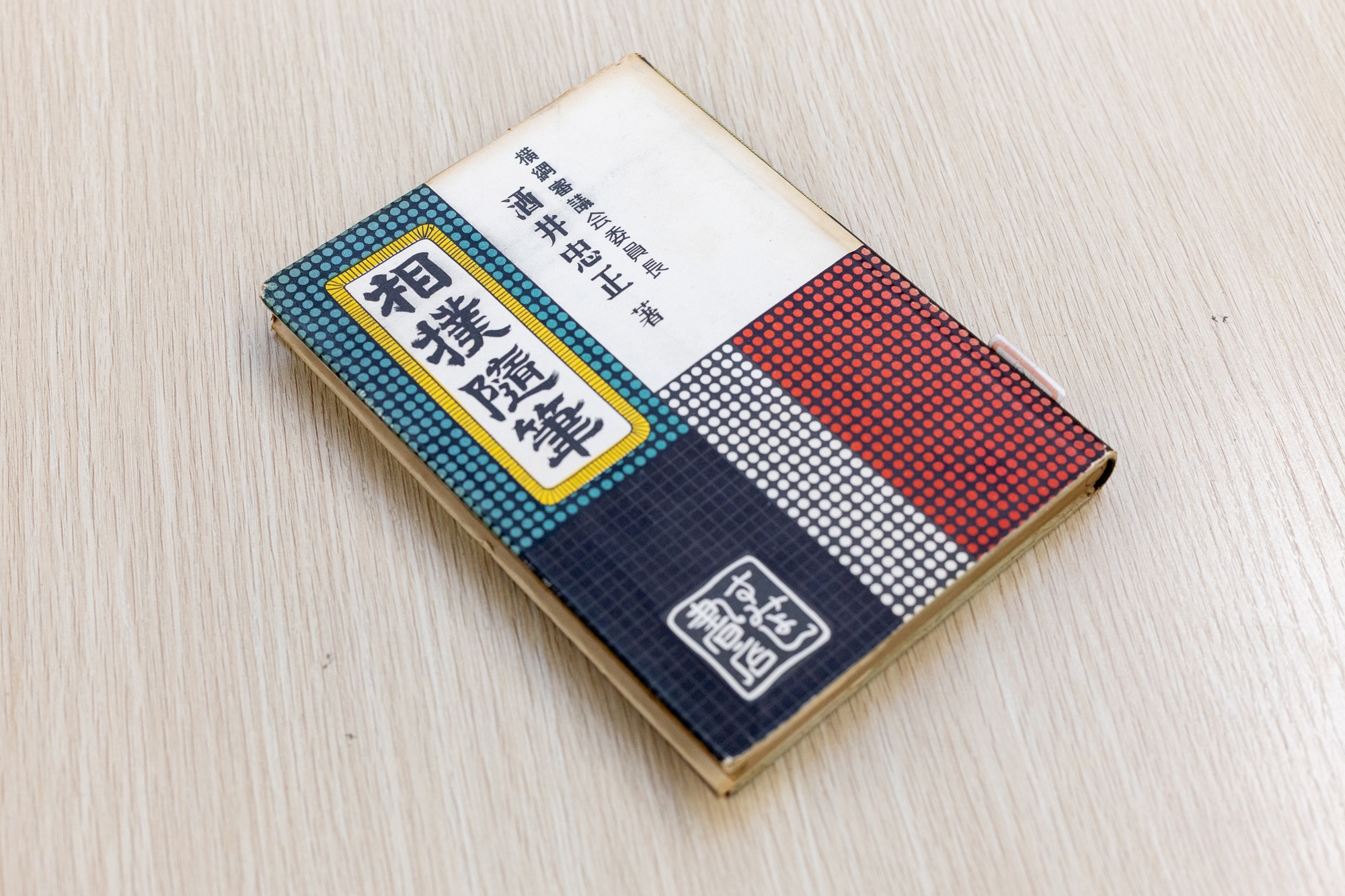

Mr. Nakamura shared anecdotes about Sakai’s collection, noting that some items are valuable fine art pieces. Sakai’s book, Sumo Essays, recounts his experiences, such as starting to collect sumo postcards around age 15 or 16, and later collecting sumo books and nishikie (錦絵). He mentions driving around in a rare and inexpensive car to buy sumo prints, only to find the prices had increased because “the person who comes in the car” was buying them.

“A large portion of the collection consists of sumo-e (相撲絵) —colour prints depicting wrestlers and matches—as well as rankings and historical sumo books. However, historically valuable art pieces include the folding screen ‘temmei hachiboshin no toshi edo ozumo seisha no zu (天明八戊申歳江戸大相撲生写之図)’ by Ryounsai Toyomaro (凌雲斎豊麿). This six-panel screen depicts people crossing Ryogoku Bridge and Nihonbashi Bridge, including sumo wrestlers. You can really grasp the scale of the wrestlers compared to the townspeople. We also have items not from Sakai’s collection, such as the Japanese sword Bizen no Suke Munetsugu (備前介宗次) (Inazuma Raigoro, 稲妻雷五郎) owned by Inazuma Raigoro, a yokozuna of the Edo period. This is a well-known sword among enthusiasts, and we have previously lent it to the Tokyo National Museum.”

A collection of 36,000 items and counting, growing with every tournament

The current director of the Sumo Museum is Hakkaku Nobuyoshi (八角信芳), the chairman of the Japan Sumo Association. “The museum is run by a staff of four,” Mr. Nakamura explained. “For special exhibitions, one person is generally responsible for the planning, sourcing exhibits, and structuring the display. We all assist with tasks, including transport and installation.”

The Sumo Museum currently holds 36,000 catalogued items. Including unorganised materials, the total collection is estimated to be around 40,000 items. While a general comprehensive museum might hold hundreds of thousands of items (including archaeological artefacts, fine arts, and natural history specimens), this is a considerable size for a specialist museum focusing on a single genre.

Alongside Sakai’s collection, many items are donations from wrestlers. Additionally, various new materials, such as rankings, match schedules, hoshitori-hyo (星取表, records of wins and losses), and handprints of new sekitori (wrestlers in the top two divisions), are added after each of the six annual main tournaments.

The Sumo Museum frequently uses its extensive collection to structure special exhibitions. The concept outline is decided about a year in advance, the structure is planned, and materials are selected over approximately six months. “For 100 Years of Grand Sumo, all items are from our collection. For some exhibitions, we may borrow kimono or kesho-mawashi from wrestlers or sumo stables. However, we rarely request loans from other art galleries or museums. Sometimes, if a popular yokozuna retires while an exhibition is being prepared, we may suddenly insert a ‘Goodbye Yokozuna Exhibition’.”

From watching Archival Footage to Rising up Sumo Ranks – Spreading the culture of ‘Grand Sumo’ worldwide

Mr. Nakamura noted that because the museum is tucked away in a corner of the Kokugikan, surprisingly many people—even those involved in sumo—have never visited. However, one particularly dedicated wrestler visited frequently during his training period.

“That was Arawashi (荒鷲), a makuuchi (幕内) division wrestler who retired in 2020. He is from Mongolia, and he often borrowed sumo DVDs to study old sumo matches and techniques. He was a dedicated student, so I was thrilled when he became a sekitori.”

Today, wrestlers still wear kimono (着物) and traditional topknots (mage, 髷), just as they were depicted in Edo-period sumo prints. Mr. Nakamura suggests that the very existence of these wrestlers, whom international visitors often admire as ‘samurai,’ represents Japanese culture.

“Grand Sumo is both a traditional Japanese culture and a sport. We hope to continue conveying the culture of Grand Sumo through various themed exhibitions.”

As the author of this piece, I always visit the Sumo Museum’s special exhibitions whenever I attend a sumo match at the Kokugikan. Despite its compact size, the museum offers exceptional value. Depending on the theme, you can encounter rare art pieces, such as Edo-period ukiyo-e and nikuhitsuga (肉筆画, hand-painted works) depicting wrestlers and sumo matches, and gain extensive knowledge about sumo.

Additionally, the museum features a service area for Nomi no Sukune (野見宿禰) Shrine, the deity of sumo. Visitors can receive popular wrestler omikuji (fortunes), goshuin (御朱印; shrine seals, available only during the Tokyo tournaments), and amulets. It is a delightful museum for both sumo enthusiasts and those who enjoy visiting temples and shrines. 100 Years of Grand Sumo is running until August 22. To get into the mood for the upcoming Nagoya July Tournament, I recommend visiting the Sumo Museum first.

■EVENT■

100 Years of Grand Sumo

Period: 11 May – 22 August 2025 (Friday)

*Opening hours and holidays are subject to the DATA below.

■DATA■

Sumo Museum

Address: 1st Floor, Kokugikan, 1-3-28 Yokozuna, Sumida-ku, Tokyo

Telephone: 03-3622-0366

Opening Hours: 10:00 – 16:30 (Last admission 16:00)

Closed: Saturdays, Sundays, national holidays, and New Year holidays (Please inquire about temporary closures)

https://www.sumo.or.jp/KokugikanSumoMuseum

Photography by: Umezawa Kaori (梅沢香織)

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/culture/276894/