Monks in colourful robes

The decision I made at the age of 38 changed my life forever.

If I had hesitated instead of taking the first step at that time, I would still be in Kyoto, a city I love, but I would not have liked myself and the grass beside me would have continued to look greener.

I was born in the oldest Zen (禅) temple in Kyoto, which has a history of over 800 years. Although I grew up surrounded by Japanese spaces, I was a sports fanatic when I was a student, and until I was in my late 20s I worked as the manager of a European antique jewellery shop, leading a life that had nothing to do with Japanese culture at all.

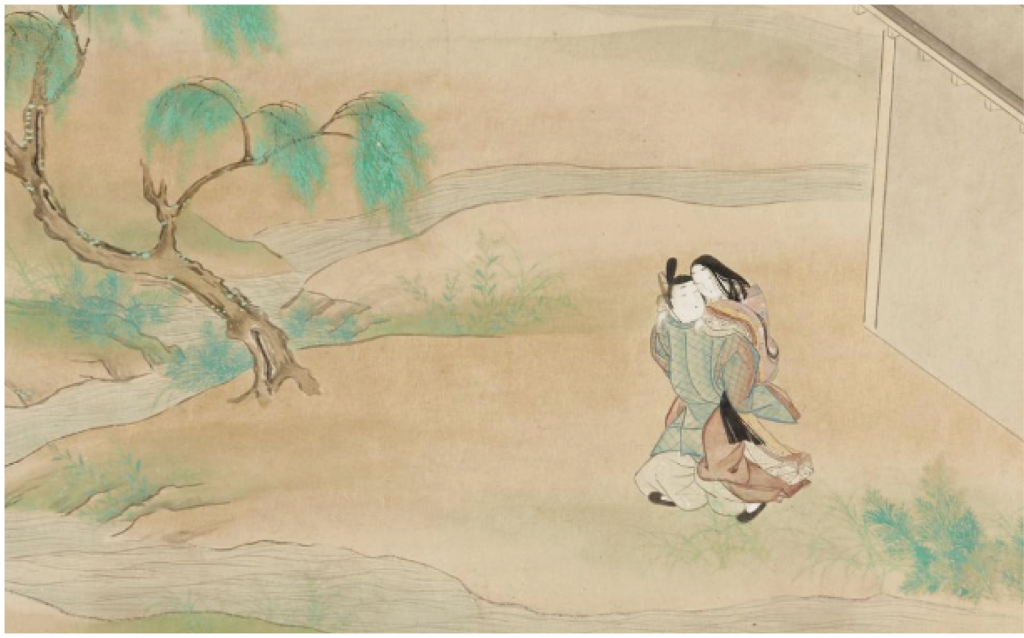

It was then that I encountered a scene at my grandfather’s memorial service that inspired me to embark on a new path. I was struck by the beauty of the colourfully dressed monks chanting, the smell of incense, the sound of mokugyo (木魚), and the way they walked while chanting, as if they were dancing.

After graduating from university, I continued my journey of self-discovery while working in a jewellery shop, and this was the moment that made me realise that what was important was not in the outside world, but within me. At the same time, the word ‘chisoku (知足)’, which I had often heard in Zen sermons, fell into my body instantly.

“Taru wo shiru (足るを知る, to know one has enough/to be satisfied with what you have)”

is perhaps what this means.

I’ve had to learn all about kimonos again, from scratch

This experience made me decide that my career path would be to convey the Japanese beauty that I had been exposed to since I was a child.

I suddenly remembered that my mother had many kimonos in her chest of drawers, and I started attending kimono dressing classes to learn how to wear kimonos. I obtained a teacher’s qualification, and while working as a dresser at wedding halls and beauty salons in Gion (祇園), I even learnt the techniques of gei-maiko (芸舞妓), and before I knew it, I had been in training for over 10 years.

Unlike western clothes, where the shape is determined by buttons and zippers, I became increasingly fascinated by the kimono, which can be freely shaped to suit each individual’s body shape and individuality, while being held in place by a single cord. I felt that the kimono opened doors to sensations I had never opened before, such as covering the body shape with the hem, expressing individuality with the collar, and expressing the ‘heart’ with the way the obi is made and the way the obi is tied.

Beyond the door that I knocked on to learn about kimonos, I found the four seasons, etiquette, Japanese colours and the wisdom of our ancestors, and I felt that I was exposed to many new aesthetic senses. I began to wear kimonos more and more in my daily life, and when I was a beginner, I often wore Oshima tsumugi (大島紬), which is easy to put on and does not fall apart.

Oshima tsumugi, which is made by yarn-dyeing and has an elegant sheen, is smooth and comfortable on the skin, so the ones worn by my mother and grandmother were excellent in terms of ease of dressing and hems, and they wiped away many of the worries of beginners.

What made me most happy was to see the smiling faces of my relatives, who happily reminisced about the good old days when they saw me in my kimono. It was around this time that I began to think that there might be smiling faces all over Japan that could be met by awakening kimonos lying in chests like this, and I started to think that I wanted to expand my mission.

Impatience to be someone else

On the other hand, 40 was fast approaching and it was becoming very difficult to find a balance between work and private life concerns. Although I was on the verge of grasping my mission of conveying the beauty of Japan to the future, I was also continuing my journey of self-discovery that I had been on since I was in my twenties. I used to go back and forth from Teramachi shijo (寺町四条) to sanjo (三条) in the downtown area of Kyoto without going anywhere.

At that moment, I suddenly had a vivid image of myself in Tokyo, a place that was nowhere for me. Unable to stay put, I immediately decided to go to Tokyo and started packing. I decided to take only what I needed for my future to Tokyo. Then I made a decision.

‘I’m throwing away my clothes, I’m living in a kimono.’

The kimonos, which have a fixed shape and folding method, fit neatly into the cardboard boxes and seemed to clear even my foggy and unorganised feelings. I realised that the kimono’s unchanged form since ancient times is due to the Japanese sense of beauty, which allows us to use things for a long time, and decided to live in Tokyo wearing only kimonos from now on.

I made the decision to let go of my clothes, not knowing if it would directly solve my problems, but to break out of a situation where I was so tight in my grip that I didn’t know what was important to me anymore. After this day, my life began to change dramatically.

My mother did not say anything when I, her 38 year old daughter, told her that I was going to Tokyo, but simply gave her a seven-coloured obidome (帯留) as a good-luck charm. On a piece of paper attached to it was written: ‘Musume yo, taishi wo idake (娘よ、大志を抱け: Daughter, embrace your ambition)’. Needless to say, those words continue to support me to this day.

This is where my kimono life in Tokyo begins.

Indeed, there is a beauty that keeps flowing through me.

The blank spaces in Hasegawa Tohaku (長谷川等伯)’s fusuma-e (襖絵) and Zen gardens.

The beauty of the white feathers and snow depicted by Ito Jakuchu (伊藤若冲).

The beauty of subtraction in karesansui (枯山水).

The beauty in the darkness faintly illuminated by moonlight.

The beauty of the world framed by a round window.

The oldest Zen temple in Kyoto taught us all this.

This article is translated from https://intojapanwaraku.com/fashion-kimono/235825/